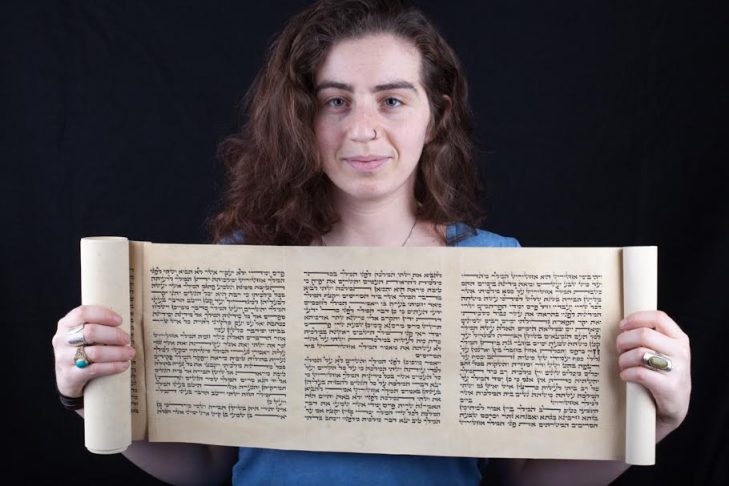

Rachel Jackson describes the megillah, or Scroll of Esther, that she handwrites as containing exactly 16 columns of 21 lines, a total of 12,111 letters. For any soferet—female ritual scribe—like Jackson, this intense labor of love and single-minded dedication takes close to 100 hours to complete and up to a year to prepare for, all in accordance with Jewish law. Additionally, Jackson cuts the quills she writes with, sews together the sheets of parchment she writes on and painstakingly proofreads her work.

Jackson, who studied philosophy and visual art at the University of Chicago, told JewishBoston that “this mindset of working as a soferet is not limited to when I sit down to work on a megillah. I was driven to learn sofrut [the practice of ritual scribal arts] because of the beauty of the craft.”

Jackson describes herself as a modern Orthodox Jewish feminist who limits her scribing to megillot (plural of megillah), meaning she lives with the contradiction that only men in her community write Torahs. “I come from a modern Orthodox background where the stated reality is that men and women are equal in terms of education, society and culture; however, the halacha—Jewish law—still gives men preferential treatment,” she said. “I feel very torn about this, but I also want to remain in my community. There are a lot of values and ways of living that only exist in the Orthodox community.”

Jackson learned the art of Jewish scribing from Jen Taylor Friedman, an egalitarian soferet based in Montreal. In addition to her superior skills as a scribe and artist, Taylor Friedman is also known as the creator of “Tefillin Barbie,” a Barbie doll that dons tefillin and a tallit. Jackson apprenticed with Taylor Friedman for over a year and produced her first megillah two years ago under Taylor Jackson’s “generous guidance.”

In an essay Jackson wrote for the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance about the intensity of scribing, she observed: “I bear the tradition of my people, but especially of my matriarchs…I see my artwork, both calligraphic and otherwise, as a continuation of a family tradition. My great-grandmother, Esther Blackburn, embroidered beautifully ornate covers for the sefer Torah (Torah scroll) and tebah (reading table) of her family’s synagogue in London. On Purim, when I hear the opening blessings as the reader begins to chant the megillah, I think of my great-grandmother and I am grateful for my opportunity to use my hands to create something which is valuable to my community.”

The memory is particularly poignant for Jackson, who considers Purim the most female-action oriented of the holidays. Esther, she observed, “was an active agent in the creation of written history.” To Jackson’s point, the megillah says, “Then Queen Esther daughter of Abihail wrote a second letter of Purim for the purpose of confirming with full authority the aforementioned one of Mordecai the Jew” (Esther 9:28).

For Jackson, anonymity is also integral to the sofrut process. She sees herself as a link in a long chain of scribes who have come before her and will come after her. As she wrote in her essay: “The goal is for my handwriting to look identical to the writing of thousands of anonymous scribes throughout the ages. For some this may sound claustrophobic. But for me it is a chance to show that I am as educated, committed and skillful as any other scribe.”

Jackson further internalizes her duties as a scribe by contemplating her Jewish practice. To maintain her status as a kosher soferet, she is mindful of her actions, whether they are related to her observance of the holidays or to daily interactions with others. She said writing megillot is incumbent upon her living a life that reflects the traditional values of Jewish texts. “On Purim,” she said, “you cannot read the megillah in any way other than from a kosher parchment with kosher ink and written in a particular way. That makes me an important part of the ritual and allows me to contribute to the life of my community.”

In addition to her sofrut practice, Jackson is honing her skills as a bookbinder, calligrapher and graphic designer at the North Bennett Street School in Boston’s North End. She recently finished writing her second megillah and has a commission for a third; her work so far has been privately collected. As she works with megillot, she is conscious that she has “spoken each letter and each word of the megillah. And just as there is a part of me in the megillah I have created, there is also a part of the megillah inside me.”

Rachel Jackson welcomes megillah commissions, as well as calligraphy and graphic design projects. For more information, visit her website.