When my first child was born, I turned to friends I saw as parenting gurus. I would sit at their table taking mental notes on their interactions with their children. They parented with purpose and intentionality, whether helping their children articulate their emotions, practice kindness and Jewish rituals or develop an awareness of social, racial and class inequities. But at one meal, while I held my sleeping baby and their kids played and read on the floor, my friend Maya shared a concern of hers. “My biggest parenting anxiety is about holding my kids back. You know, what if they have the potential to be professional bobsledders, but I never gave them the chance to try it? I might be shutting them out of their ultimate purpose.”

Of course, the example Maya picked was meant to be ridiculous. But Maya’s concern reflected one of the most widespread philosophies of parenting today, what sociologist Annette Lareau calls “concerted cultivation.” This is the idea that parents, especially those parents with the affordances of money, resources and time, see parenting as a set of intentional choices designed to help their children succeed and find meaning in life. These choices include what kinds of extracurricular activities their children will do, what kinds of experiences they will have and, perhaps most importantly, how they will be educated.

Based on the evidence of extensive observations and interviews, Lareau argues that concerted cultivation works. On average, children turn out more or less the way their parents hope they will. Given the resources to do so, parents can effectively shape their children into the people they want them to become—beekeepers, blacksmiths or even bobsledders. This education starts long before they ever enter a classroom and extends far beyond the school day.

Which brings me to Jewish education. Choosing to send your children to a Jewish day school is one of the most important choices a parent makes for their children. Every parenting choice is a choice not to do something else. In their famous study of parent decision-making around Jewish day school, Cohen and Kelner (2007) find two main reasons parents choose not to send their children: money and the fear of what they call “ghettoization.” I want to address these two concerns and then explain why I chose day school for my own children.

Cohen and Kelner found that despite the perception that the cost of Jewish education is prohibitive, most parents actually make a value calculation. This distinction, while subtle, is important. In other words, parents are making a choice to spend dollars that could be spent on Jewish education on something else.

The second reason parents don’t send their children to day school is the fear of “ghettoization,” that is, a fear that day school represents a kind of bubble and their children will miss out on the diversity that makes for a well-rounded and socially-aware adult.

Perhaps counterintuitively, I send my own children to Jewish day school precisely because I feel that day schools may better equip my children to function in a diverse, multifaceted society. I want them to be grounded and immersed in a particular world of culture, language and texts that is their own, and which I believe provides them with an incredible set of tools for thinking, living and navigating across the various kinds of differences they will encounter in the world. I am not convinced they will learn these skills in the same way at the same depth in any other kind of school. Of course, not every day school does this, but I believe this represents the ideal.

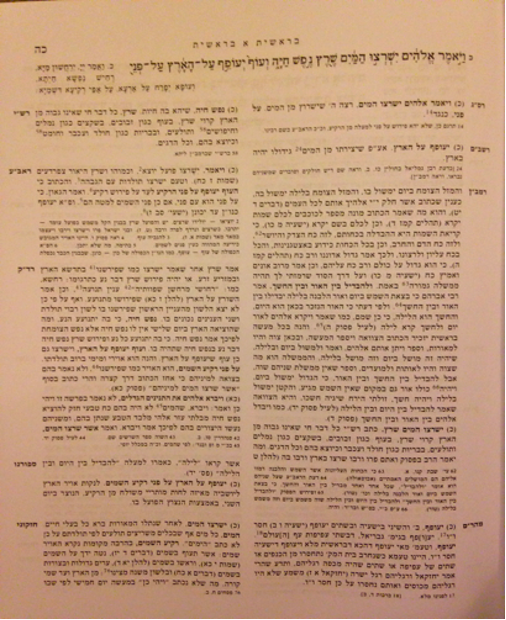

For me, the paradigmatic example of how day schools can teach kids to encounter differences lies in how biblical texts are read and taught. When Jews study Torah, the text rarely appears alone; it is accompanied by many commentaries. In the example below, the biblical verse is followed by nine different commentaries composed across Jewish history from the second century to the 19th century. These commentaries represent a conversation—often a fierce debate—that has taken place over thousands of years.

The traditional layout of the Hebrew Bible constantly reinforces the value of multiple interpretations, and that Jewish learning approaches a text as fundamentally ambiguous and able to accommodate more than one “right” answer. This task of learning how to hold multiple interpretations is at the heart of Jewish learning and is the skill I value most in Jewish education. This skill, to listen carefully to what others say, ground your own beliefs in close reading and evidence and to remember that there are limitations to any position or worldview transfers “off” the page. It is a skill that comes into play when reading people, situations and contexts. When my kids spend half their day engaged in Jewish learning, they are not only learning their own history and culture but they are learning a way of thinking and reading that is a deep training in empathy and perspective-taking. This is why I choose to send my kids to Jewish day school.

In a recent interview for JewishBoston, my colleague, Dr. Jonathan Krasner, the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Associate Professor of Jewish Education Research at Brandeis University, offered some historical perspective to the Jewish day school movement to JewishBoston readers. Dr. Krasner concluded with the following important insight: “Equally important for the long-term sustainability of the non-Orthodox day school sector will be its ability to embrace and celebrate an increasingly diverse Jewish population and speak the language of millennial parents who value diversity and tend to be socially conscious.” When taught well, Jewish text learning can be the cognitive training that accomplishes this, teaching students to instinctually embrace and celebrate diversity—of interpretation, thought and life.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE