Earth Day is April 22. This year, it falls on the 17th of Nisan. But it isn’t always on the 17th of Nisan. It doesn’t begin in the evening and end in the evening. We don’t light candles or eat special Jewish foods. There are no special prayers. We won’t find Earth Day on the Jewish calendar.

Sounds like it isn’t a Jewish holiday.

And it isn’t. At least not officially. And yet, there is so much about Earth Day that is Jewish, beginning with the story of creation in the first chapter of the Torah. All the universe is part of that story, including this precious planet.

In the second story of creation, the Garden of Eden presents an image of what life on earth could be like, and in that image we read that God placed ha’adam, Adam, the person, in the garden, l’ovdah ul’shomrah, generally translated as “to till and to tend it” or “to cultivate (or work) and keep it.”

What might our relationship to the earth look like if we were to think about it as though we were ha’adam in the Garden of Eden? Another meaning for the root ayin, vet, dalet is “to serve,” either a ruler or God. What might our actions in connection to the earth look like if we considered all of them as service to God through the maintenance of this Divine Creation upon which we live? How might we behave in relation to the trees and sky and water and fungi and whales—and everything else?

We have many opportunities in the Jewish calendar to consider our relationship to the earth—Rosh Hashanah, sometimes described as the birthday of the world; parashat Bereshit, when we read the creation stories; parashat Noah, when we read about the flood, parshiot Mishpatim and B’har, when we read about letting the earth rest during the sabbatical year; and Tu BiShvat, sometimes known as the “Jewish Earth Day.”

But there are actually so many other opportunities. A reading through the five Books of Moses provides encounters with the earth in one way or another in almost every weekly portion. God told Abraham that his offspring would be as many as there are stars in the sky—is that the starless city sky or the dazzling wilderness night sky? Jacob laid his head upon a stone at night and dreamed of angels going up and down on a ladder—is that a bit of the crushed gravel in one’s garden or driveway, or a red desert rock? Sacrifices were made of animals in fire. The list goes on and on. And if we turn to the Psalms, there are even more references to the natural world.

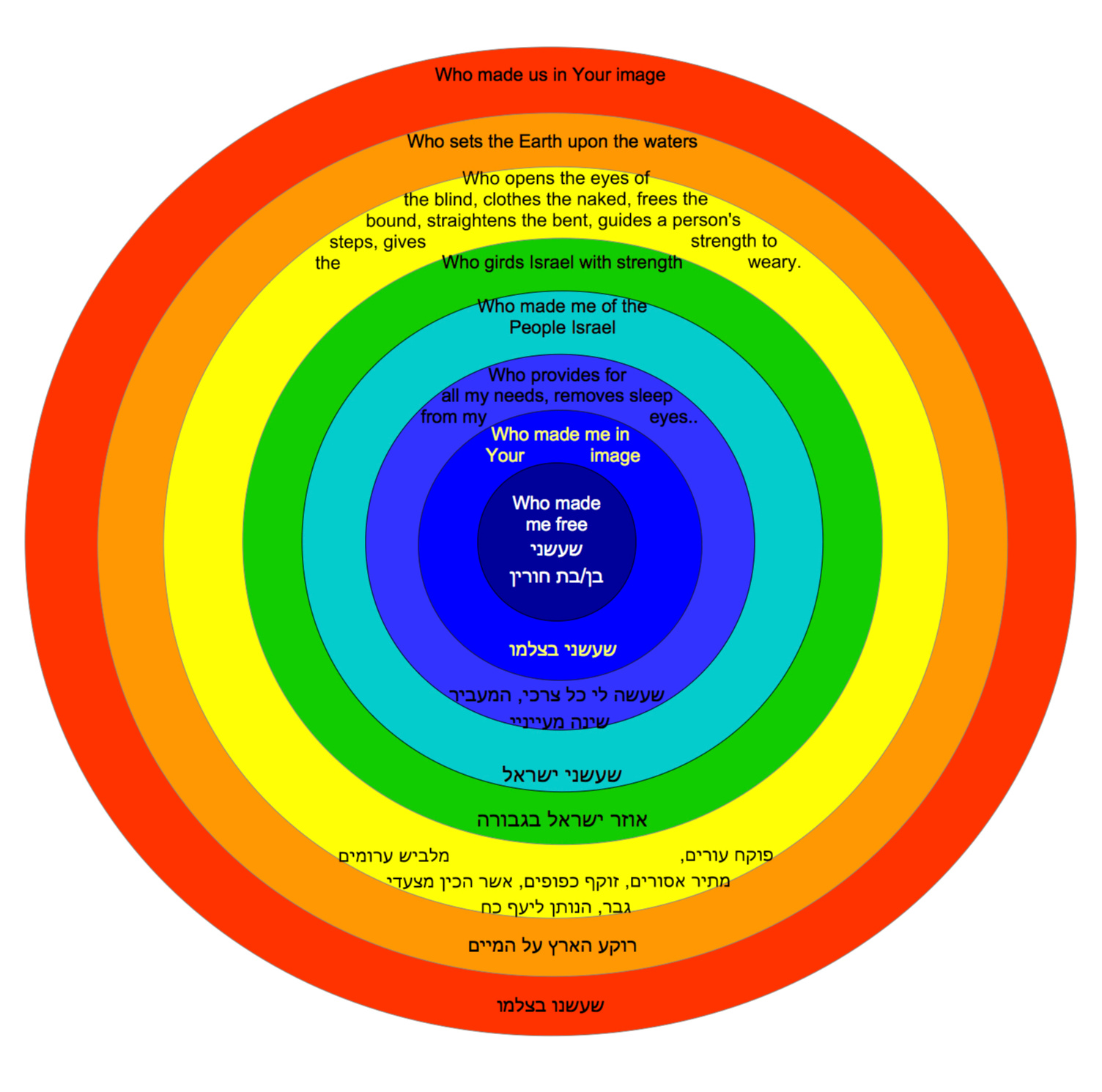

Another way to consider Judaism’s connection to the earth is in the morning blessings, Birkat HaShachar. In the diagram below, the 13 short blessings have been rearranged and placed in concentric circles, starting with the person reciting the blessings at the core. The blessings in blue express what is being requested or stated in a very personal way, beginning with the understanding of our own free will. Moving outward to those that are related to being part of a community, the Jewish people (in green), “who made me of the people Israel” (turquoise) expresses the transition from the personal to the communal. In yellow are blessings that are universal, such as opening the eyes of the blind. In orange are two blessings that relate to the natural world, widening our connections to include the earth and its more-than-human inhabitants.

At the outer edge of the diagram, in the deep orange, is an extra blessing not in the siddur, but in the spirit of Jewish tradition. Rabbi David Seidenberg in his seminal work, “Kabbalah and Ecology: God’s Image in the More-Than-Human World,” presents a clear case that everything, not just humans, but the plants and animals and rocks—everything—is created in God’s image. As a second grader explained, when presented with the idea of a blessing, “Who made us in your image”: “It comes from the creation story, because God created everything.” So, it must all be in God’s image and therefore sacred.

And returning to the dark blue, the core, God made us free—free to choose how we will be in relationship to the sacred earth.

From an understanding of the earth as sacred, as created by God, as made in God’s image, the Jewishness of Earth Day becomes readily apparent. Earth Day is a reminder of the sacredness and importance of the earth and of our role and responsibility in maintaining it for all its inhabitants, both human and more-than-human. It is a reminder that there is a time and a place when the secular becomes sacred. It is a reminder to renew our effort to preserve this planet while it is still possible, because it is up to us. We are free to choose to stand idly by or to act and “keep,” or preserve, this amazing planet and all it contains.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE