On the Shabbat morning of Oct. 27, 2018, a white supremacist attacked the three Jewish congregations holding their services in various spaces within the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood. When the rampage was over, 11 people were dead in the worst antisemitic attack on American soil.

Days after the murders, journalist Mark Oppenheimer was on the ground in Squirrel Hill. Over 18 months, he made 32 trips to Pittsburgh and interviewed over 250 people. The project was personal for Oppenheimer; his forebears were founding members of the Pittsburgh Jewish community dating back to the 1840s.

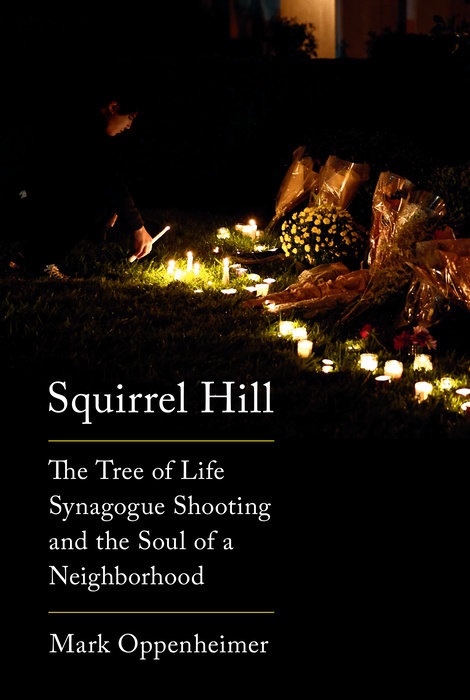

Oppenheimer’s impressive reporting and research is the basis of his new book, “Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood.” In his meticulous chronicle of the shooting’s aftermath, Oppenheimer establishes Squirrel Hill—a unique Jewish neighborhood in the annals of American Jewish history—as a formidable character.

Jews have continuously lived in Squirrel Hill for over a century, experiencing much less “white flight” for the suburbs than other cities. In the book, Oppenheimer observes that the Jewish community continued to thrive in Squirrel Hill after day schools, the Jewish Community Center, Jewish Family and Community Services, several synagogues and its federation made the decision to stay in the city.

To this day, Squirrel Hill is still a place where residents regularly bump into childhood friends. It’s a community-minded locale where Jews of all stripes comfortably mingle at the Giant Eagle Supermarket or Murray Avenue Kosher. Oppenheimer portrays the large table in the neighborhood Starbucks as a symbol of the city’s amiability. After the shootings, the table was a destination for grieving friends and planning gatherings to commemorate lives lost.

Oppenheimer also tracks several acts of grace in the wake of the shootings. There was Greg Zanis and the “crosses for losses” he carves and delivers to tragedy sites; he fashioned Stars of David for the Tree of Life victims. There was the lapsed Catholic artist who made public art for the Starbucks windows, and there was the Orthodox rabbi who led a group that performed sacred funeral rites for the victims.

Oppenheimer is a former religion columnist for The New York Times and host of Tablet Magazine’s podcast “Unorthodox.” He lives in New Haven with his family, where he directs the Yale Journalism Initiative. He recently spoke to JewishBoston about his new book.

What distinguished the Squirrel Hill shooting from other mass shootings?

Squirrel Hill is rare among American mass shootings in that it was an event whose victims were people who knew each other: They were friends and part of the same community. They were united in purpose and prayer. Mass killings in America typically happen to groups of people who have nothing in common until that day. These shootings occur at shopping malls, post offices and movie theaters, where people are accidentally together. That leads to a very different response, which can lead to many hurt feelings, acrimony and misunderstanding in the survivor community afterward. Parkland was different in that, obviously, these were students who went to school together, though it’s still the case that the families probably scarcely knew each other. What happened in Squirrel Hill is most similar to the shooting at Mother Emanuel Church in South Carolina.

Eric Lidji, the archivist at the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Senator John Heinz History Center at the University of Pittsburgh, had the job of choosing artifacts to represent that tragic day. How did that weighty responsibility affect the choices he made?

Eric never expected that he would be in a position of archiving material from a mass killing. No archivist thinks that’s what they’re getting into. It was a difficult job for him, but also one with a lot of purpose that he took very seriously. As I say in the book, he had very tough decisions to make because you can’t save everything. An event like this generates enormous amounts of paper; it generates thousands of get-well cards, thousands of bouquets, hundreds of teddy bears, candles, little paper angels and thousands of stones left at the site. You have to draw the line somewhere. So he had a very heavy set of choices weighing on him, and he still does because stuff keeps coming.

What were the pros and cons of the Squirrel Hill community’s apolitical stance?

There is no one authentic response to the Squirrel Hill tragedy. For some people, it was important that their loved ones’ deaths not be politicized, not be yoked to any policy position, political agenda or candidate. Just as surely, there are people who feel that the only authentic response is the one that changes the world through politics and policy. So there’s no reconciling the two impulses. It seems to be the case that the majority of victims’ families were in the apolitical camp when it came to commemorating their losses. But there were people who suffered that day, either personally or by losing relatives. Some would have preferred that there would be talk about gun control and mental health treatment every time their loved ones’ names were mentioned.

What will happen to the Tree of Life building, which sits empty behind a chain-link fence?

I understand that there will be a partnership between Daniel Libeskind, a very famous architect, who was the master planner for the Ground Zero site, and a local architectural firm to figure out what to do with the Tree of Life site. I think there will be some sort of major renovation that will include worship space and museum and educational spaces. There are many schools of thought about whether Squirrel Hill needs another multipurpose Jewish space, given that there’s already the Jewish Community Center and two synagogues that have large spaces available for use.

Whatever Libeskind and others come up with will probably be very expensive. There is not enough money raised right now to pay for a multimillion-dollar renovation that also brings everything up to code. So there will be more fundraising. My prediction is that whatever the tab is, a wealthy person will sweep in at the last minute and make up whatever the shortfall is. This event is so indelible in American Jewish history that somebody will feel compelled to make sure that Tree of Life has the funds to do whatever it wants to do. But we are at least three years, and probably more like five, away from any building re-opening on that site.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I found it beautiful to see what people did with not only words but pictures too. For example, graphic designer Tim Hindes’s design “Stronger Than Hate” was an amazing riff on the Pittsburgh Steeler’s logo. The public art made for the Starbucks windows was also very affecting. And the headline in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which was the first line of the Mourner’s Kaddish in Hebrew letters, was a stroke of genius by the executive editor at the time, David Shribman, a native Bostonian. He was also a former editor at The Boston Globe.

Mark Oppenheimer will be appearing at events all over the country, including Boston College on Tuesday, Nov. 9 (register here).