Rabbi Moshe Rosenberg, author of “Morality for Muggles: Ethics in the Bible and the World of Harry Potter” and “The (unofficial) Hogwarts Haggadah,” is at it again with “The (unofficial) Muggle Megillah.” Released only two weeks before Purim this year, “The (unofficial) Muggle Megillah” aims to show Harry Potter readers that “so much of what delights us in [Harry’s] story can be found in an intelligent reading of scripture” (pg. 5). As someone with a BA in English who lived for writing papers that explored literature through philosophy and psychology, I could get behind this idea. I was even, dare I say, excited to see how Rabbi Rosenberg compared stories to each other this time around rather than transforming a story to fit a prayer book. Unfortunately for Rabbi Rosenberg, his third attempt at this profitable thesis isn’t successful.

The first thing you experience when embarking on this journey is confusion. The layout of the megillah is this: The Book of Esther in Hebrew on the left even pages and in English on the right odd pages, essays trying to connect Harry Potter with the story of Purim, a “Student Voices” section wherein he asked his students questions that have nothing to do with what he expresses in the essays that precede them, “Royal Trivia” questions with difficulty levels to start each “chapter” and an “end notes” (annotations) section containing three things from only one chapter. His essays do not have pages of their own and do not at all match up with the Hebrew and English megillah text under which they are crammed. He also needs to pick between citing just the books or just the movies—don’t allude to one or two things from films, which I’ve heard take extensive liberties like manipulating the plot and leaving out crucial characters—just like Rabbi Rosenberg does.

Related

The annoying “Student Voices” section he insists on including in both the Haggadah and megillah hint at younger reading levels and are irrelevant. “Who is your favorite secondary character in tanakh?” (pg. 39). Seriously? Yet he includes words like ad hominem, antithesis, bildungsroman (though the included definition—nice job—could have just been “a coming-of-age novel”), pernicious and pervasive. What audience did he really have in mind?

I think he read my takedown of his atrocious Haggadah, though, because there are noticeable improvements in this new project. Myriad confusions aside, to his credit, he shows a much more thorough and accurate knowledge of the book series. Even still, like Rita Skeeter, Rabbi Rosenberg “present[s] facts partially, [sic] and then ask[s] leading questions” to “lead most readers to the wrong conclusions” (pg. 30).

Spoiler alert reading forward: The entire “Harry Potter” book series.

Rabbi Rosenberg starts the first chapter off strong by juxtaposing Lucius Malfoy with King Ahasuerus and his lavish parties…but, wait, no Haman? Lucius Malfoy uses his wealth and favor with the Ministry of Magic to protect himself against accusations. Isn’t that what Haman does? He also compares Harry’s financial benevolence toward his friends to Esther’s refusal to ask for gifts from the king. Interesting but kind of a stretch.

Another essay, entitled “The Art of Slander,” kicks off with a discussion about the “evil spies of the Bible, [sic] who wanted to persuade the Children of Israel not to enter the Promised Land, began [their lies] with a truth” (pg. 28). This is the section with which I had the most issue because Rabbi Rosenberg demonstrates a complete lack of knowledge about the focus of this essay—defamation—and therefore misrepresents characters and plot points.

For him to use an argumentation tactic correctly (“ad hominem”), despite it being a logical fallacy, and then to not understand the difference between libel and slander, is just sloppy (pg. 28). (Slander is spoken, libel is written; think “s” for slander and speech, and “l” for libel and literature.) To prove defamation, “the statement must have been made with knowledge that it was untrue or with reckless disregard for the truth.”

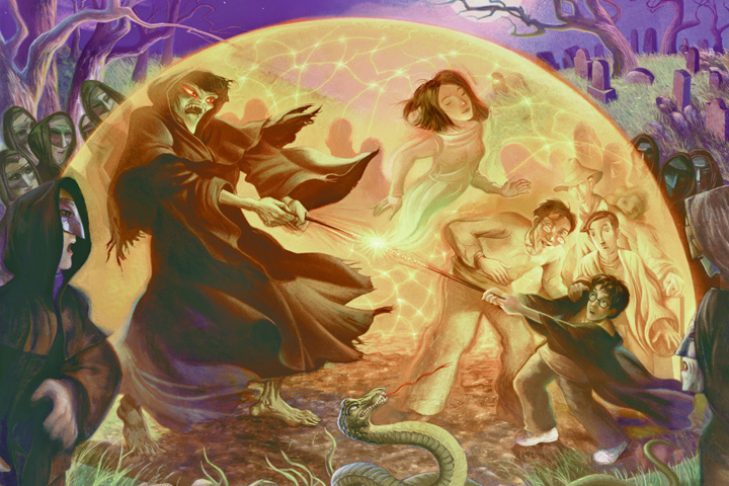

He abandons Voldemort’s actions and true character in order to match Haman’s deliberate lies and manipulation. Voldemort does not commit slander; he’s a narcissistic villain who fails to understand Harry’s enormous capacity to love. He’s incapable of seeing the truth so he can’t disregard it. Even still, Voldemort addresses only Harry during the scene in question, looking directly at him and using “you” and “Potter.” That’s not slander. (Fun fact: This is the book’s only paragraph in which book quotes are cited with page numbers.) Haman, wishing to eliminate Mordechai, has no problem lying about him to the king.

You want to talk defamation? I got you. Mentioning the Quick-Quotes Quill is a solid step, but let’s go further. Second to the main story arch in “Deathly Hallows,” Harry’s quest to separate truth from libel in Rita Skeeter’s book—“The Life and Lies of Albus Dumbledore” indeed—creates rifts in his relationships with Ron and Hermione and almost derails their horcrux hunt because Rita’s false words make him feel deceived by his mentor.

Rabbi Rosenberg was trying to make everything Harry-centric but failed time and time again, even holding back on specific and important plot points and, again, omitting crucial characters.

The character to whom Mordechai most resembles would be Dumbledore, probably Sirius (who isn’t even mentioned), maybe Lupin (who is)…not Harry. Yet Dumbledore is glanced over like he’s nothing in this section. Like Mordechai, Dumbledore was the master planner. In order for Harry to defeat Voldemort and unite the three hallows to become the master of death, Dumbledore plans for Hermione to figure out the symbol in the book he left her in his will; and he gives Ron the deluminator with the power to transport him back to Harry and Hermione when he leaves out of anger because Dumbledore knows he would want to come back. Dumbledore also imparts the knowledge on to Snape that Voldemort needs to kill Harry first before he can be destroyed.

Harry doesn’t lay “his plans meticulously before entering the fray”; he isn’t expecting to sacrifice himself at all (pg. 36). War is war and unexpected stuff happens. The only thing he plans while walking to the forest to meet his assumed death is telling Neville that Nagini had to be killed. That’s it.

As Mordechai did with Esther, Dumbledore encouraged Harry to embrace his gifts, which Rabbi Rosenberg so poignantly pointed out on pages 36-37 to great effect. This was my favorite part because what he writes about the unification of love as Harry’s ultimate weapon was great and even enhanced the magic of that scene for me. There, I said it.

A few other quick points:

- Real talk: If Esther is like anyone else in the book, it’s Neville. Let me adjust Rabbi Rosenberg’s words on page 32: “By the time the reader reaches [book] seven, the full contours of [Neville’s] character—[his] courage, [his] command of the situation, sense of responsibility and grace of implementation—are evident.” Well, maybe not that last one… it’s Neville.

- How did the essay on humility not mention Dumbledore, who recognizes his power in a humble way?

- Again, Rabbi Rosenberg’s refusal to understand fictional wand lore obscures the plot: Harry didn’t “tame” the Elder Wand, he won it. Harry was the true master of the Elder Wand because he took it from Malfoy by transitive property. His ability to love didn’t make him the wand’s tamer, just its conquerer. Dumbledore tamed it, as he says in the “Kings Cross Station” chapter in “Deathly Hallows” (pg. 40).

- Elphias Doge was not blindly loyal to Dumbledore! The man wrote a passionate epitaph (that Harry keeps!) describing how Dumbledore befriended him when no other kid would because he was recovering from dragon pox.

- One of the answers to the “Student Voices” question about how to respond to an insult is “punch the guy in the face” (pg. 30). Unlike most of the other “Student Voices” responses across the book, this one does not have a name next to it. Let’s chalk that up to sloppy copy editing because it could give the impression the suggestion came from the author.

- Ron. Is. Missing. Again. Harry saved “the lives of Arthur and Ginny”…and Ron! (pg. 66). Just like Mrs. Weasley says in “The Half-Blood Prince” after Harry shoves a bezoar down Ron’s throat to save him from poisoned mulled meed.

- Voldemort’s “pointy stick” (pg. 30). ‘Nuff said.

Rabbi Rosenberg got me in the end. He stumped me on one (non-film) trivia question about which character purposefully destroyed their clothes. Touché.