One of the things the Book of Genesis has taught us is that chaos is a precursor to creation. The first verses of the Bible describe an “unformed earth”—void of anything bearing a resemblance to earth as we know it. Next, there was water and wind, and then the presentation of light. God, the mystical artist of all that is holy, needed the new light to illuminate the world—to separate the day from night. As the week went on, God worked their way up to creating man and woman.

The second chapter of Genesis tells another briefer version of the creation of the world. We’re told that the earth is barren—not a shrub or patch of grass in sight. There was no one to till the land—there was no rain to encourage growth. To solve that problem, God quickly “formed man from the dust of the earth. God blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and then man became a living being” (JPS translation).

God is the world’s first visual artist with the soul of a storyteller overseeing the narrative of our creation. The scheduled reading of these Torah portions begins anew on Simchat Torah. Genesis, or Bereisheit, as it is known in Hebrew, will be read on Shabbat on Saturday, Oct. 2. For the occasion, I turned to Deb Putnoi, artist and creator of The Drawing Lab, to put a fine point on the creative process. In the two decades since its founding, The Drawing Lab has inspired everyone from shy kindergartners to reluctant adults to free up their innate creativity.

Putnoi is also the author of “The Drawing Mind: Silence Your Inner Critic and Release Your Creative Spirit,” an interactive sketchbook that charts the reader on a course to silence their inner critic. The Drawing Lab and “The Drawing Mind” work in tandem. “The lab is the place where you’re experimenting,” she said. “For example, what does it mean to draw your sense of taste, to taste a piece of chocolate? The drawing mind is to activate the part of brain or soul and mind that is inside of us.”

Putnoi has brought her unique, supportive approach to art to classrooms and Jewish spaces alike. She’s created programs for synagogues and for Mayyim Hayyim where people’s drawings, among many things, have been responses and interpretations of Jewish objects and concepts. Putnoi has a hard and fast rule before anyone puts pencil to paper: No one is allowed to say they can’t draw, and there is no wrong way to make art. “I’ve been in classrooms where drawing has changed the tenor of the room,” said Putnoi. “Kids who are silent find a voice. Drawing also builds connections and democratizes the classroom. When I bring The Drawing Lab to schools, teachers participate with the kids. They’re scared to draw too, so they become a part of this exploration of our visual voice.”

Putnoi asserted that there are no mistakes in her Drawing Lab. That idea, she said, “brings us back to a central part of ourselves, who we logged off of very early. We have pushed away from this false impression that we’re not artists or we can’t create art. And we’re scared of the process.”

She inspires hands to keep moving as she aims to engage body and soul. Her methods focus on conquering the performance anxiety that can come when creating any art. It’s the terror of the blank page, the blank screen. It’s overcoming inhibition, a need for perfection that takes over when starting something new. As God shows us in Genesis, beginnings are hard.

To address built-up fear, Putnoi starts with the basics. First, she asks budding artists to make a fast line on the page. It’s a confidence booster, she said. “Marks are the language of drawing,” she added. “If you look at any drawing from Van Gogh, Picasso or Klee, or the sculpture of Louise Bourgeois—they all began with marks. When you notice that, you see the breadth of artistic creation. It’s an infinite language, and once you get comfortable with your mark-making, you can build from there.”

In another exercise, Putnoi asks everyone from kindergartners to adults to do what she calls a “pre-cow drawing.” It’s a five-minute exercise to establish a baseline. Putnoi said the first iteration of cow drawings is tentative; there are many unfinished drawings and drawings with many cross-outs the first week of the lab. However, over the following weeks, the fear dissipates.

Over two months, Putnoi gives her students innovative prompts. She’ll ask them to draw renditions of smell or taste, or happiness. Then she’ll direct them to put their hands inside of touch boxes where an object is hidden inside. “Working with abstraction is a challenge,” she said. “You’re never drawing what the thing is; you’re drawing the experience of the sensation of touching it.”

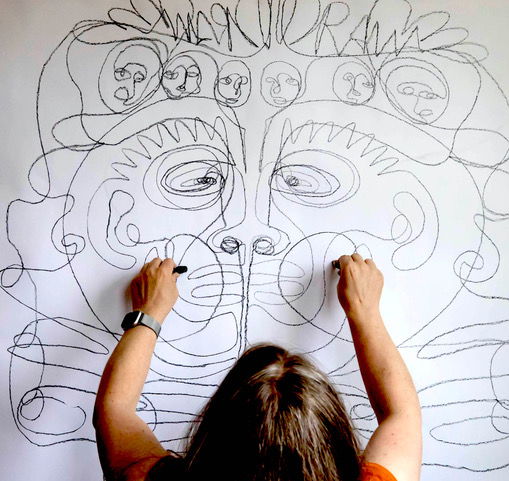

Putnoi elaborated that her program is split between the mark-making side of things and blind contouring. Blind contouring drawing is sketching a face or an object without ever looking down at the paper. “I call it a deep looking experience, where, not thinking, you see something. It’s a meditative experience that helps individuals to let go of that sense of perfection and control. You’re looking very carefully, yet you’re not criticizing what’s on the page.”

There are many ways to practice blind contouring. Putnoi has her students do it with one hand, with two hands or the opposite hand. “I’m always pushing my students to disrupt how they normally do things,” she said. “Sometimes I ask them to close their eyes. It’s a disruption because they won’t draw a perfect piece with two or opposite hands. It slows them down and, in the process, it can be messy or chaotic. But that is a crucial lesson.”

Through The Drawing Lab, Putnoi has expanded the idea of what a drawing can be and what art can do. “The first thing I have people do is scribble,” she said. “I tell them to move their hands and experience what it feels like.” And as it was at the beginning of creation, magic and holiness emerge from that chaos and messiness.