Hillary Chute’s fascination with “Maus” goes back over 20 years. Now a distinguished professor of English and art & design at Northeastern University, Chute remembers the moment she was first inspired to study Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust graphic novel in an academic context. It was in the fall of 2000, when she was a graduate student at Rutgers University during the presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore.

“It was seared into my memory,” Chute said. “I would come out from my room in Brooklyn, New York, where I was living, look at the TV, and go back and work on my paper about ‘Maus.’”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus” has inspired her current work as a scholar of comics and graphic novels. She wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on “Maus” and collaborated with Spiegelman on a subsequent work, “MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus”; released in 2011, it won the National Jewish Book Award. She is also the editor of a forthcoming book, “Maus Now”; the title references some of Spiegelman’s more recent lectures about “Maus.” It’s all given her perspective to discuss the Jan. 10 decision by a Tennessee school board to ban “Maus” from its eighth-grade curriculum.

“On one level, I was stunned, because the reasoning is so bizarre, in my view,” Chute said. “On the other hand, I wasn’t surprised, because ‘Maus’ is a book that has always elicited lots of really strong reactions across the spectrum. It’s not that I think that’s a good thing. But I’ve always understood ‘Maus’ is a controversial text, a sticky text.”

Since that vote by the McMinn County School Board, a new controversy arose. While discussing the school board’s decision on “The View,” panelist Whoopi Goldberg said that “the Holocaust isn’t about race” but rather “about man’s inhumanity to other man,” explaining this by calling the Nazis and Jews “two white groups of people.” Goldberg, who has apologized, received a two-week suspension for her comments.

Related

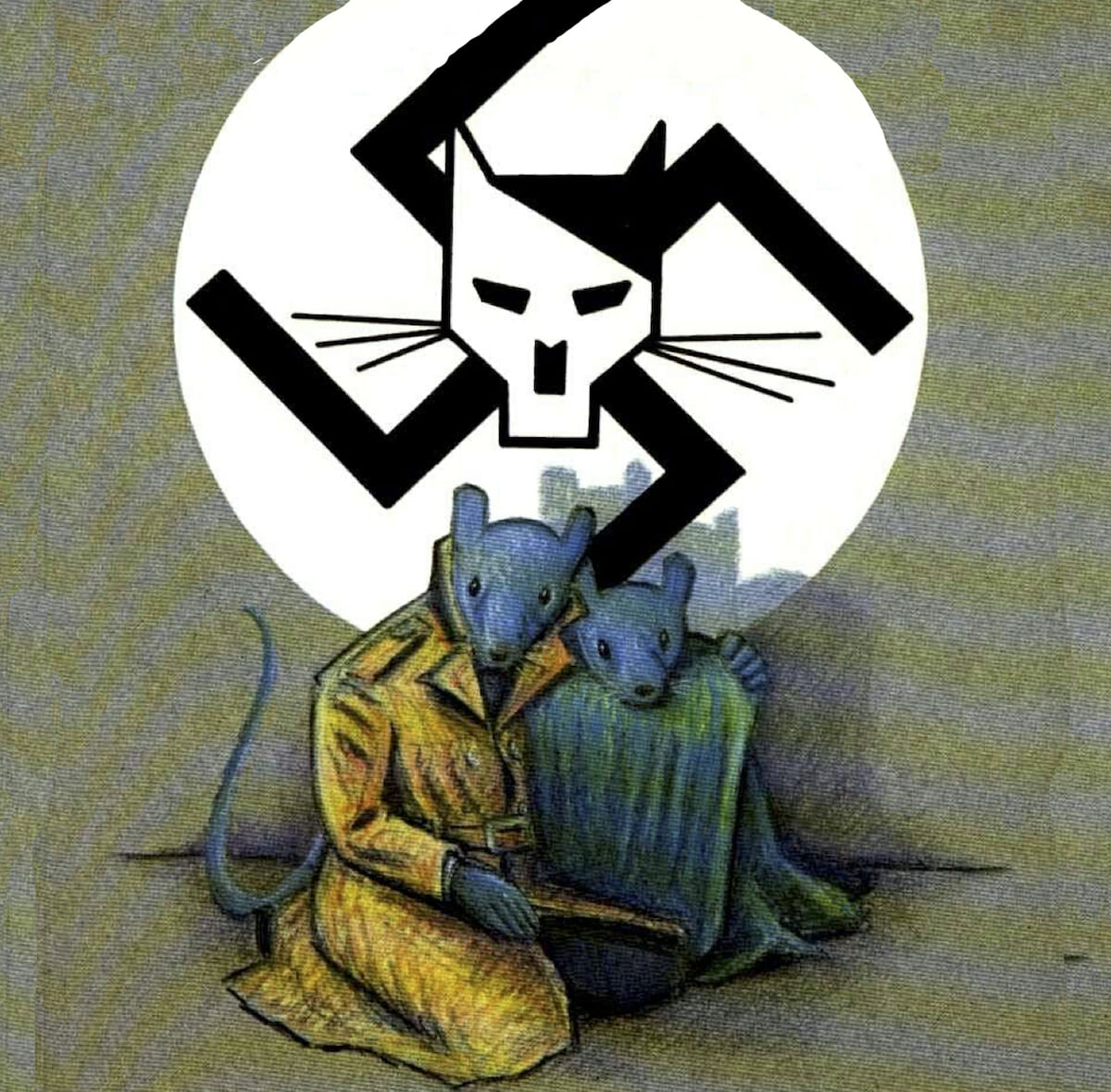

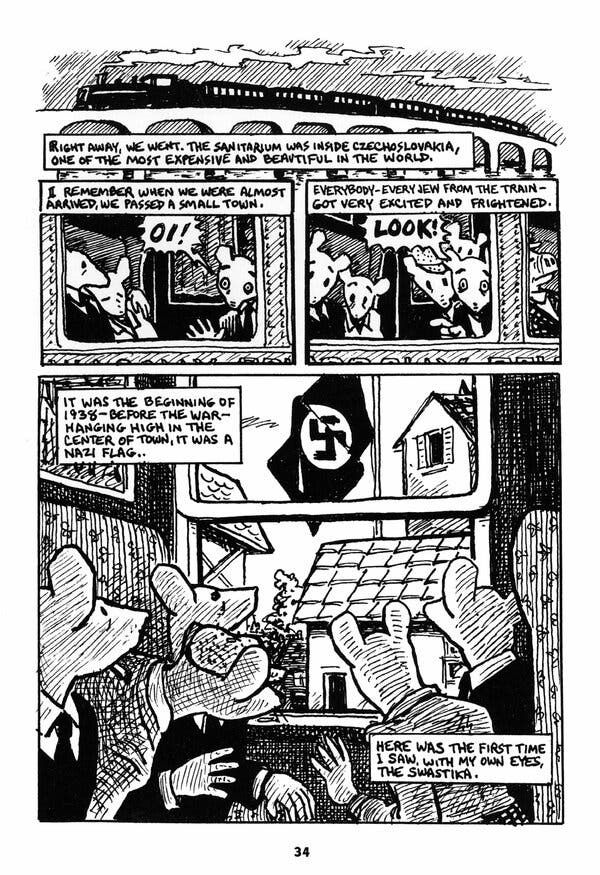

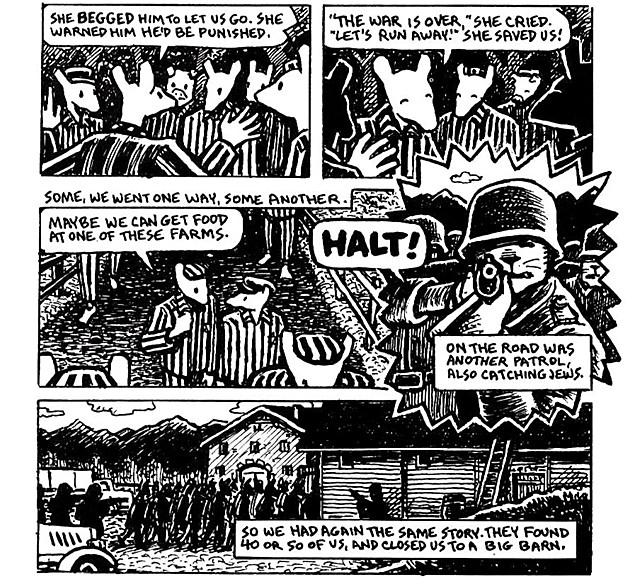

Released in two volumes—the first in 1986, the second in 1991—“Maus” uses allegorical imagery to tell Spiegelman’s family narrative. Spiegelman depicts Jews such as his father, Vladek, as mice, and the Nazis who imprison them at Auschwitz as cats. The story is shared through interviews between Spiegelman and his father, with the time frame shifting between the past and present.

When the school board voted to remove “Maus,” members cited such reasons as offensive language and nudity. Yet Chute found a more revealing moment when a member objected to a panel showing a hanging of Jews.

“To me, it was the moment I felt that now it was clear what was going on,” Chute said. “It did not have to do with bad language, it did not have to do with nudity. It does have to do with moments of violence in the book that are instrumental in describing the kind of stuff that was actually happening [in the Holocaust].”

At the school board meeting, educators defended the use of “Maus” in the classroom because of its historical accuracy, according to a transcript.

“It was very powerful for me that instructional supervisors reminded the school board that this is history, this happened,” Chute said, “not just [to] Art Spiegelman’s family, but millions and millions and millions of others.”

The 10-member board unanimously voted to remove “Maus” with the possibility of replacing it with a yet-to-be-determined alternative.

“I think it’s ominous—I think Spiegelman called the whole event a ‘red alert’—if ‘Maus’ is taken off and there’s nothing currently on the books to fill its place,” Chute said. “Perhaps there might just be a long process [to replace it].”

Yet, she added, “the erasure of the reality of Jewish history is very disturbing and upsetting, and the bigger picture about the surveillance of what educators are teaching at the high school, middle school, university and college levels, to me is just galling and horrifying.”

She teaches “Maus” to her college and graduate school classes at Northeastern, and notes that it has been taught to students as young as middle school.

“It lets students access history through the story of one family,” Chute said. “I think that’s a really crucial way to start looking at this history [and] open it up for young readers. Maybe ‘Maus’ is a good example of some of the explanations of what comics can do best—approach and address history in a compelling and also a sophisticated way.”

Spiegelman has also sought to talk more about the book from a Jewish perspective following the antisemitic attacks of recent years, Chute said.

“Obviously, it’s a Jewish book. It’s about Jewish people,” she said. Yet, she added, “I think, for a couple of decades, he did not feel very comfortable with the idea of ‘Maus’ being read as a Jewish book. He did not want it to be pigeonholed.”

However, Chute explained, “Starting with the deadly Charlottesville racist rally, followed by the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, he has changed his mind. He started giving talks and lectures around the country, around the world, titled ‘Maus Now.’” And, she added, “‘Maus’ is important right now, because of lots of reasons, including the reason of horrifying antisemitic actions happening in the past few years.”