Walking the streets of my Jerusalem neighborhood, I could hear the synagogue singing of communities from Syria, Iran, Greece, Europe, and Ethiopia. Yet the journey that led me to my current interest in global Jewish musical traditions has been far from obvious. Born into a secular family in Israel, where the connection between religious institutions and the state is highly contentious, I was educated to stay away from anything religious. Despite my exposure by osmosis, I had no structured education about Jewish art.

“The historian is the physician of time. It is his honor to heal wounds, genuine wounds. As a physician must act, regardless of medical theories, because his patient is ill, so the historian must act under a moral pressure to restore a nation’s memory, or that of mankind.”

—Eugene Rosenstock-Hussey

This quote, shared with me by Jewish educator Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld, encapsulates my desire to use the opportunity of the Creative Community Fellowship to be an agent of healing. First, I hope to expand and refine my own awareness of the incredible variation and depth in global Jewish art. To share this richness with the local community, I am designing workshops that will provoke audiences to question their notion of what Jewish music is. In doing this work, I see myself as part of a generation of young artists who are working to revive historical traditions and reject ideologies of assimilation that have led to cultural erasure. It is my way to heal wounds.

When I moved from my native Jerusalem to Boston in 2017 to attend Berklee College of Music, I never imagined that two years later I would be learning about Appalachian ballad singing in an attic in Durham, North Carolina. A random hallway encounter with Paul Rishell, a master of country blues music, has led me to years of dedicated study focused on vernacular forms of American folk music. I consider myself privileged to be able to continue performing and studying with incredible musicians in this domain. In 2021 I was stuck at home due to the pandemic. I was missing the sounds of my home. I found comfort by playing Ladino (Jewish-Sephardi) songs that I remembered listening to as an adolescent. This experience started me on a journey into the richness of an almost extinct musical tradition. As I learned more about the Spanish expulsion, it revealed itself as one chapter of a timeless Jewish story. Time and time again, Jews have moved through the cycle of exile, assimilation, and violent persecution. I began asking myself: “How did Jews across time and culture preserve their identity, while trying to assimilate in their dominant host culture?” I am fascinated by this tension and the unique art it has generated.

The research I have begun as part of the Community Creative Fellowship allows me to deepen my understanding of my own idiom. At the same time, it is broadening my perspective as I make connections across the arts. Over the course of this fellowship, I would like to implore audiences to join me in considering the question: “What makes a particular text so powerful and universal that it survives centuries of persecution and forced migration?

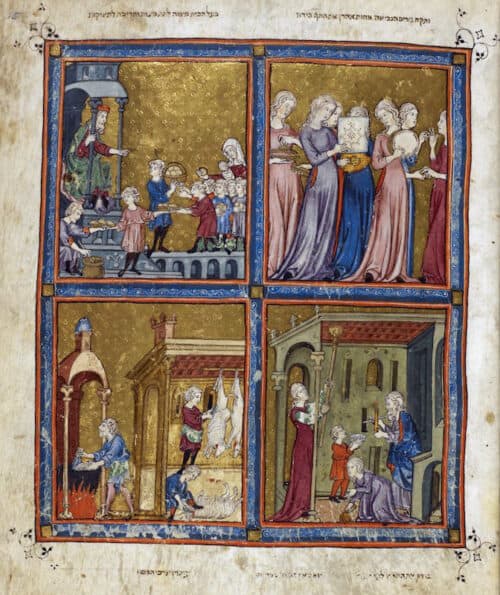

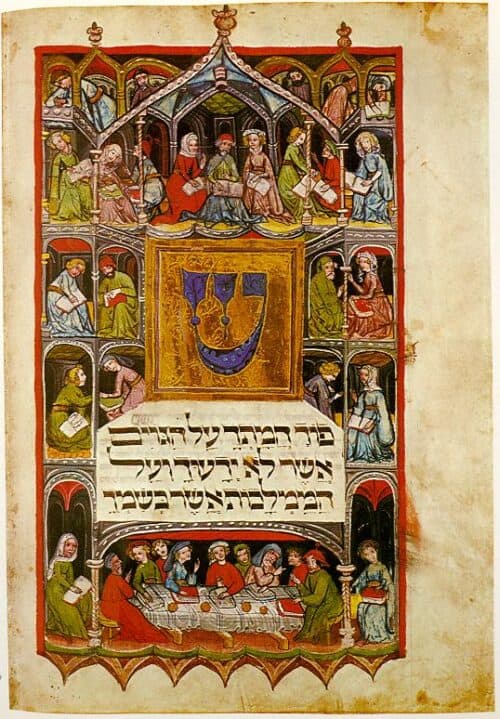

To begin, I welcome you to listen to the piyut “Adon Olam” (אדון עולם) on the website of the National Library of Israel. This traditional prayer has been part of the Yom Kippur service for centuries in communities across the Jewish world. The website includes recordings of 49 different variations of this prayer, from Yemen to Frankfurt. Similarly, we might look at variations in illuminated manuscripts such as these Passover Haggadah pages originating in Spain and Germany.

Looking at both prayer and visual art, we can observe the same, unique cultural pattern—using the contemporary artistic styles of the dominant cultures around them, Jewish communities have been able to express, preserve, and refine their own culture. An uncanny, radical, and subversive act.

The historian is the physician of time. It is his honor to heal wounds, genuine wounds. As a physician must act, regardless of medical theories, because his patient is ill, so the historian must act under a moral pressure to restore a nation’s memory, or that of mankind.

The preservation and restoration of memory may be the healing work of the historian. Yet to me, the work of the artist goes a step further. Once the memory has been restored, the artist reframes and expands it, creating the next page in a timeless story.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE