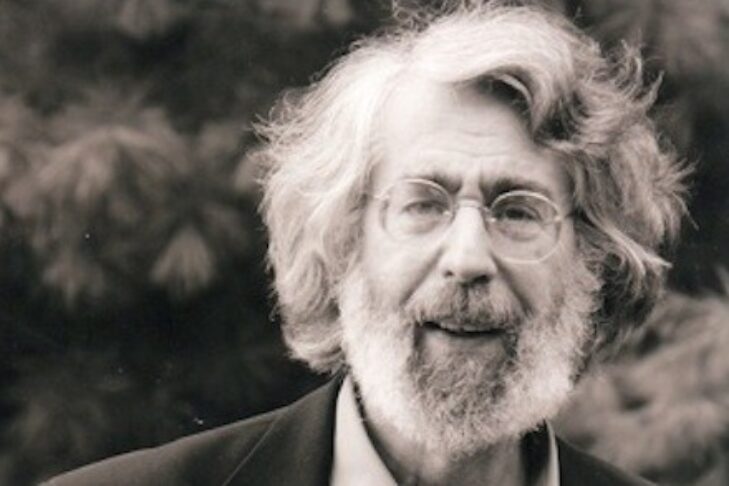

The poet and music critic Lloyd Schwartz arrived at Harvard University in the late 1960s to pursue a Ph.D. in English. Two life-changing things happened to Schwartz in Boston—he met the legendary poet Robert Lowell at Harvard and published music criticism beginning in the early 1970s. Both these formative events came together to lay the groundwork for a flourishing literary career.

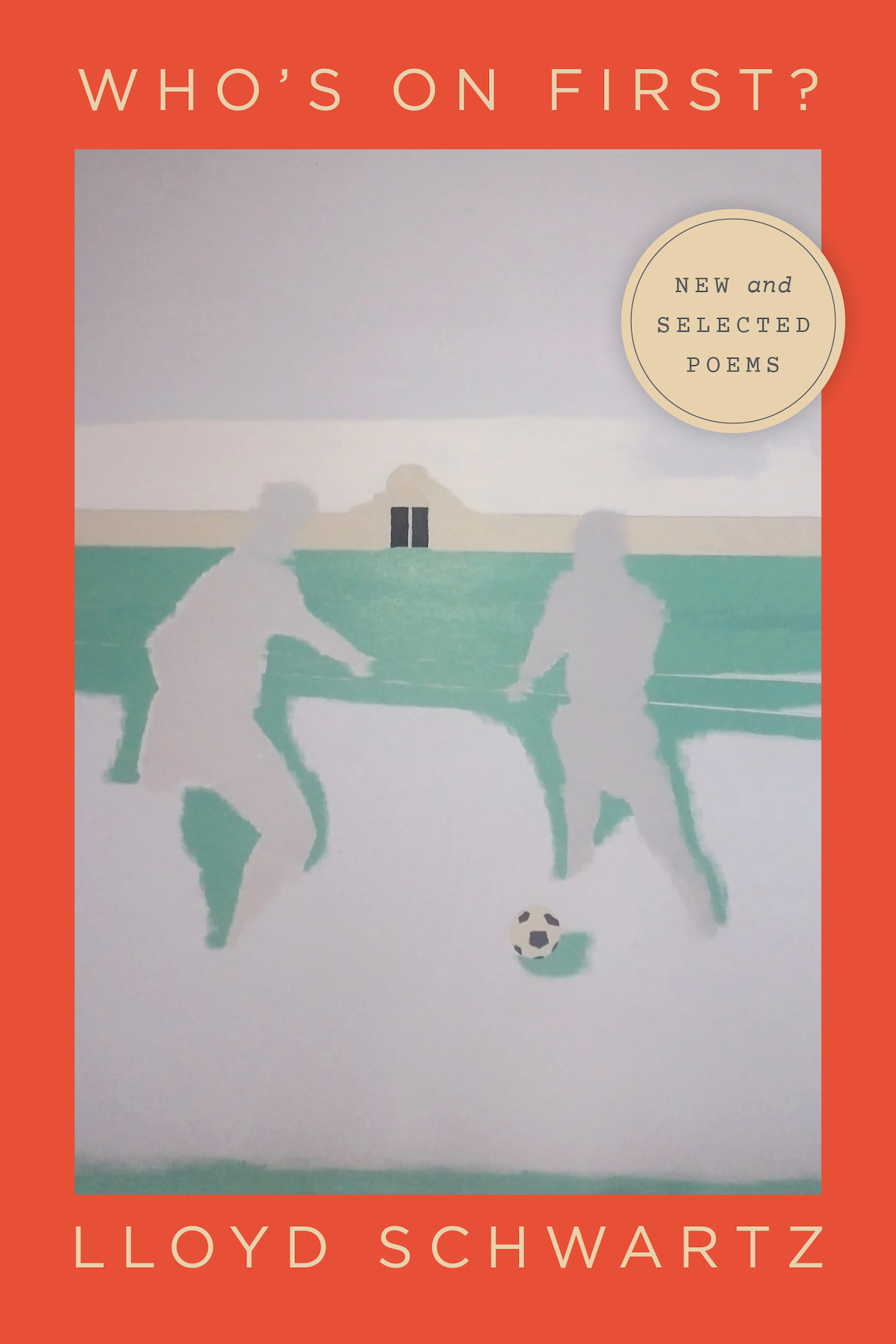

In 1994, Schwartz was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in criticism “for his skillful and resonant classical music criticism” published in the Boston Phoenix. His latest collection of poetry, “Who’s on First? New and Selected Poems,” features a grouping of poems—many of them award-winning—from his first four books.

Schwartz grew up in Queens, New York, speaking Yiddish to his grandmother, who lived with his family. His mother encouraged his literary and musical ambitions by reading poems and introducing him to Broadway. In anticipation of his Dec. 17 event with Jewish Arts Collaborative, Schwartz recently spoke to JewishBoston about his poems, early influences and his late mother’s unwavering support. One of my favorite writers, Natalia Ginzburg, said everything we write is a little autobiographical. You have a line in “Self Portrait,” one of the earlier poems in “Who’s on First?” that reminded me of Ginzburg’s observation. You write: “Every painting is a portrait.” Can you expand on that? “Self Portrait” is one of the earliest poems I wrote about my best friend, the painter Ralph Hamilton. A detail from his painting “Soccer Players” is on the front cover of “Who’s on First?” Something shifted in my writing in the early ‘70s. I was teaching and still in graduate school, preparing to be an academic. I was also writing poetry and wanted to be an actor. I was doing a lot of plays, mostly in Cambridge in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and met some wonderful young actors. I loved teaching, academic work and the theater, but I could see that some of my very talented colleagues couldn’t even get a job doing commercials. I was just too scared to risk everything to become an actor. So, I started writing poems in other people’s voices. And one of those first poems was “Self Portrait” about Ralph Hamilton’s self-portrait. When he said, “Every painting is a self-portrait,” it connected to what I was doing as a poet. My poems were either real or completely imaginary. It’s like the actor who becomes another character. Acting was a way of both escaping myself and extending myself. I was playing parts that I could never be in real life. Suddenly I wasn’t acting, but I was writing these poems that were in the voices of other people. Whatever impulse I had as an actor, I shifted it to writing poems. In the poem “Ralph Hamilton’s Faces,” there is the line, “‘Looking at Hamilton’s portrait,’ a viewer observed, ‘like being in the middle of an intimate conversation.’” Do those lines reflect what you are trying to accomplish in poetry? I would like that to be true of my poetry, which is so true in those portraits that Ralph did much later in his career. And he did about a hundred of them, including portraits of my mother and father. Ralph took photographs of the people he painted. Some were stars, some were family members and some were just people he knew. Once he felt that he was in conversation with the figure he was painting, the painting was done. I think that, in some way, that is true of these poems. They are conversations or feature someone talking. The poems about your mother are very moving. “She Forgets” captures a universal experience, as well as the sadness and the tragedy particular to you and your mom. I’d like to point out the first lines for your comment: “The one who told me about the Holocaust, who taught me moral distinctions, who gave me music and told me jokes is in a nursing home: lonely, scared, surrounded only by people so much worse off (inarticulate, incapacitated, drooling, she thinks she’s in a crazy house.” The lines also speak to how your mother raised you. Tell me about your mom. The poems about my mother are very important to me, and I think they’re some of my best work. I don’t know another person in the world whom I admired as much as my mother. She was a wonderful, generous, interesting person. She was the youngest of five children, and like her siblings she was born in Russia. She had to leave school when she was barely a teenager. Her older siblings were married, and she was the only one left to take care of her parents. This was in the 1920s. My mother was the first woman to drive a car in her neighborhood. She loved Broadway shows, and this was all before she got married. I think of her as a kind of flapper—as someone who was out there enjoying herself, someone who was up to date with the newfangled inventions. When she finally married, she was almost 40. My mother taught me how to read and write before kindergarten. She also taught me English and, obviously, Yiddish, which we spoke at home. The saddest thing about my mother’s dementia in her late 80s was she always felt something was missing. Her identity was slipping away, and there was nothing to replace it, and that was heart-breaking. How did your mother influence you as a poet? She had a book of great English language poems, which she read to me from. She loved popular music, which I do, too. So, she was always singing or playing records, and I learned the lyrics to popular songs from listening to her and the radio. You won the Pulitzer Prize for your music criticism published in the Boston Phoenix. It sounds like your mother had a hand in that. My mother was the first person I called when I found out I had won the Pulitzer. I said to her, “Do you know what the Pulitzer Prize is?” And my mother said, “Yes. Did you get one?” The following day there was a picture of me in The Boston Globe on the phone with my mother. I had great editors at the Phoenix who cared about writing and journalism. I learned tremendously from them. I also had a week to write a piece for the Phoenix rather than the hour I had when I reviewed concerts for the daily Boston Herald.

Related