The morning after news of the Orlando massacre broke, my son had a kindergarten orientation at the school playground. I stood there in my smiley-face name tag watching the 5-year-olds swinging and thought to myself: “I wonder how many of these innocent kids might get shot one day?”

Morbid, right? But I don’t think it’s that unusual. Many parents I talked to after the fact felt the same way. There’s a sad futility, a pervasive terror, when we consider the fact that our children are so vulnerable. Orlando, Newtown, San Bernardino: It could be any one of us, at any time. Our children just don’t know it yet.

In times like these, it’s easy to wonder what the point of spirituality or faith even is. How can we have faith in a higher power when this kind of chaos surrounds us? How can we feel secure in a world that’s so unsafe?

I talked to two local rabbis to ask their opinions. They had such smart things to say that I’m presenting their (slightly abridged) words below, because these aren’t soundbites. They’re worth thinking about and drawing some sense of solace and strength from at a time when we all feel so helpless and scared.

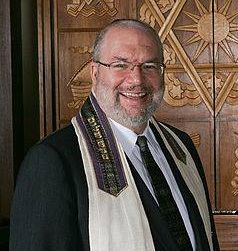

Senior Rabbi Howard Jaffe, Temple Isaiah, Lexington:

The world is fragile. We know that we are always vulnerable, and events like this remind us of how vulnerable we are. But they should sharpen our awareness and make us more devoted to minimizing them.

As far as questioning one’s faith in God, I think the question itself suggests a misplaced responsibility. It suggests that somehow God is responsible when human beings act evilly. It suggests that somehow, especially when there is a larger number of individuals impacted, we expect God to suspend the rules of nature in intervening in human life in ways we might not expect in any other circumstance. Any time there is a particular tragedy, our question tends to be, “Where is God?”

The correct answer is that God is with those who are weeping and wounded. God is with those who are binding those wounds. God is with the caretakers and the surgeons and the medical personnel and all others who are helping people get through this. And our faith has to be in our capacity not to despair and not to give over to the forces of evil and darkness.

I would quote the medieval Jewish philosopher Bachaya Ibn Pakuda, who said that all of life is about balance. We are never able to achieve perfect balance, because that suggests that there is such a thing. Just as one would not dance as they’re crossing a busy street, one always has to take note of our surroundings and our reality. Be as fully present as humanly possible. Make sure we have moments where we’re safely standing on the sidewalk. There are times to be secure, and times to be more vigilant.

After 9-11, we were more vigilant than we had ever been before, but as we got used to the idea that there was not likely to be an attack every day, we stopped turning on the radio to hear if something else was happening. Eventually we were more comfortable with airplanes, going to concerts, et cetera. We need to take the time to mourn, grieve, recognize evil, put it in its place, and never stop living. When we do, that is when the forces of darkness win. When we despair, because we’re only looking over our shoulder, we’re not also living. We’ve lost the battle.

When talking to children, I would never lie. Never say, “Don’t worry; it can never happen to you.” The world is a place where dangerous things can happen, and we can never promise completely that nothing bad will happen. But think about all the children who get up, every day, how many thousands of days and millions of children get up and go to school and come home and are all OK. Think about those. And know that every time we think about this, the grown-ups are even more careful and making sure even more that everybody is OK.

The more the forces of darkness operate, the more light we need to bring. I would tell my children: “In times like these, you need to make sure you are even more loving and caring. That is the only way to win. To have more good things in the world, we must be as good and caring as we can be.”

Rabbi Bill Hamilton, Congregation Kehillath Israel, Brookline:

Fundamentally, just in terms of the decisions we make and the wisdom we impart, we tend not to be at our best when we’re afraid, angry, confused, exhausted, in pain or drenched in cynicism. This doesn’t mean we cannot express ourselves well when one of those conditions prevails, but in terms of our decision-making, we’re not at our best when we’re off balance that way.

One of the functions of spiritual elements is to get at the place where we can restore our equilibrium and rebalance ourselves, so we can bring responses that are credible and helpful and healthy to really painful and severe traumatic experiences.

What we want is to believe in people and the world. I like to focus on the victims and the heroes, re-instilling a belief in our kids and in each other that there are heroes. We should emphasize to our kids that there were heroes, and recover that belief.

Bad things can happen. God prefers goodness to perfection. We could all be made into robots, but wickedness is about human free choice and free will; God values freedom above all else, and so we have the freedom to do sacred and good things and the freedom to do bad things.

So why are we still here? Every time we reveal our glowing humanity, it’s as if God is saying the cost is immensely high to give people free will, but that person’s choice in that moment may make it worth it in the end.

For children, it’s important to validate their feelings, and it’s important to reassure them that they’re not wrong to be sad and afraid or upset. But we can focus on the heroes and not the horrors, not the single bad actor but the dozens of good actors. We can’t be 100 percent certain about what will happen tomorrow in terms of our safety, but we can believe deeply in people’s glowing humanity and the way in which they step up to prove the vast majority of people are empathic and generous.

Around the High Holidays, I ask, “If someone were to say to you a year ago that the following things will happen—you will face a struggle in your marriage, lose your job or lose a loved one—what would happen?” People often say they wouldn’t be able to handle it, and please, don’t let this happen. But here we are, a year later, and maybe you did deal with these things, and you’re still here. You thought you couldn’t until you were called upon to survive it.

In this way, we can see the evidence of having been touched by God’s clear preference for resilience, hope and a way forward.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE