Leann Shamash gives her adult education students a deceptively simple task: find what is hidden in the objects they photograph. Shamash, a Newton-based photographer, has been teaching a course for Hebrew College’s Open Circle program this semester with the evocative title, “Feasts, Fasts, Fakeries: The Scroll of Esther Through a Photographic Lens.”

For two hours on six successive Sundays leading up to the Purim holiday, Shamash has asked her students to read a chapter in the Book of Esther closely each week. From there, they glean themes that deepen their understanding of the text and inform their photographic process. Shamash said this considered approach is a marked contrast to how the Megillah is usually experienced. “When we read Megillat Esther, it’s in the synagogue and somebody is rambling through it,” she said. “We’re not really taking it in. The other way we see the Megillah is through Purim shpiels that take the holiday’s base themes and make them into musical comedy. But there’s a lot more to the Megillah, and reading it closely allows my learners to find themes and photograph those themes.”

Last fall, Shamash offered a similar class on “The Book of Bereishit [Genesis] through Photography.” Rich with family drama, sibling rivalry, parental favoritism and jealousy, Bereishit offered her students various themes. “Bereishit is rich in dysfunction, making it a good vehicle to probe and take images,” said Shamash. She noted that the Megillah is similarly rich in images and ideas. However, there are also issues connected to women, issues of being included in power—particularly royal power—that also tugs at the imagination.

Additionally, there is the fact that the Megillah is the only book in the Jewish canon that takes place entirely in exile. It is also a book where God is seemingly not in the details; in fact, there is not a single mention of God.

Shamash encourages her students to seek out photography forums to view other people’s work that may jumpstart their creativity. The goal is to see how other photographers interpret themes her students may want to investigate. “In the spirit of hiddenness, I ask everyone to take one object and photograph it many times to find what is hidden within it,” she said. “And in that same assignment, they can also find something on the ideal of beauty or the idea of Esther.” By the end of the assignment, students have applied the same skills to interpreting a text and taking a picture.

Shamash emphasized that she is more of a guide than a teacher in the course. Her students are in charge of choosing their themes and creating their presentations. Shamash herself is a student of photography. This month, she will be part of the Photography Atelier, a student exhibition at Winchester’s Griffin Museum of Photography, for the second time. She will be presenting photographs inspired by her participation in Daf Yomi—a seven-year study of the Talmud done in concert with other participants worldwide. This is the second year of the cycle, and Shamash has taken the current subject of Daf Yomi about fasts, integrating Talmudic texts in her photographs on the subject.

Taking up Daf Yomi also coincided with the year Shamash said the Mourner’s Kaddish for her mother, Irma. In her first exhibit at the Griffin, she presented a series of photographs of her mother called “A Series of Hats.” Shamash said photographing her then-95-year-old mother in various hats “is the project I’m most proud of.”

As her year of mourning began, the pandemic brought people together on Zoom, transforming the notion of community. Shamash said the Mourner’s Kaddish virtually with the minyan at Congregation Kehillath Israel in Brookline. She took pictures of her fellow mourners and minyan attendees in their Zoom boxes. “It’s a tiny piece of history during COVID,” Shamash said.

As a mourner, Shamash also started writing poems based on the weekly Torah portion. “The process of writing poetry meant that I needed to read the parashah more deeply,” she said. “I had to explore a theme to write a poem. I’m a learner more than anything, so it was magic for me to have a voice in poetry. I wanted people to be able to do the same thing in photography that I was doing to create my poetry.”

Shamash has discovered unique commonalities between the visual and the written worlds. In both arts, she noted, “there are themes rushing underneath the surface, but if we don’t take the time to look at them, we don’t know what they are. Once we know them, we can create around them in images or poetry.”

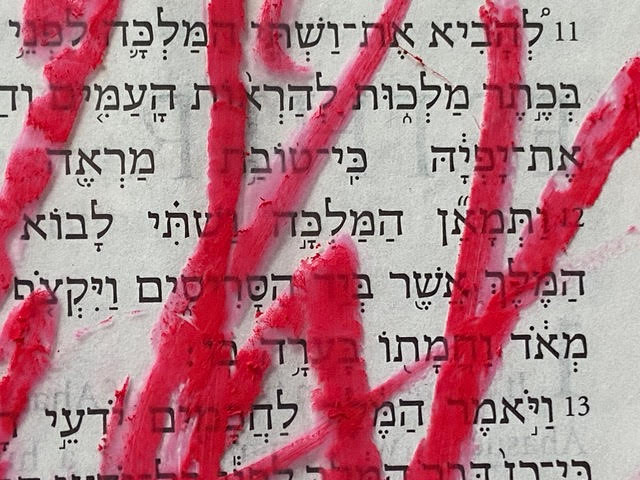

Shamash also said her students have taken the themes of hiddenness and beauty inherent in Purim to create expressive images. For example, one student took a picture of a piece of text from the Megillah and placed a plastic sheet over it, which she colored with an oil crayon. The effect was a striking image of beauty that brought to mind the strokes of bold red lipstick. Another student took a simple picture of her makeup kit inspired by the second chapter in the Megillah. “That chapter,” said Shamash, “talks about how women entered the harem a year before they were sent to the king. It was a year where they had oils, incense and perfumes.”

Shamash hopes to help her students cultivate a sense of awe and amazement in their photographic practice. “Abraham Joshua Heschel said we need to see the world with a sense of ‘radical amazement.’ It’s a religious experience of the world,” she said. “I hope to make a practice of that for myself and my learners with photography. You just have to look up and down and all around you to see the miracles that are everywhere.”