This is the season to delve into Psalm 27, which brings forward the complicated relationship between King David as psalmist and God as his benefactor. For more than 200 years, it has been traditional to read Psalm 27 beginning in the month of Elul and continuing through Sukkot. The psalm is a confrontation of personal faith as King David struggles to balance his role as warrior and penitent. By the end, David can step back and survey his life. It’s also a psalm full of familiar lines, such as:

One thing I have sought from Adonai—how long for it:

That I may live in the House of Adonai all the days of my life;

That I may look upon the sweetness of Adonai,

And spend time in the Palace.

The translation is from Rabbi Debra J. Robbins’s book, “Opening Your Heart with Psalm 27: A Spiritual Practice for the Jewish New Year.” Her book serves as a template to considering and deploying the psalm’s meditative qualities.

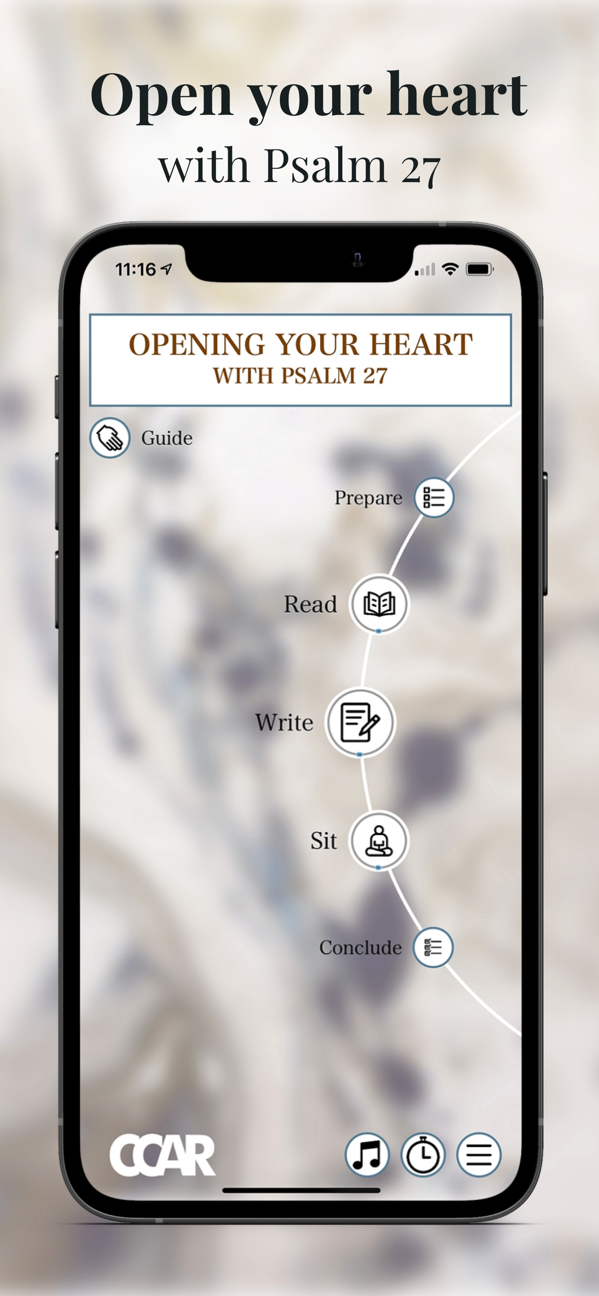

CCAR Press recently launched an app based on the book. Rabbi Dan Medwin, director of digital media for the Central Conference of American Rabbis, is responsible for bringing Psalm 27 into our daily lives via our smartphones and tablets. He recently spoke to JewishBoston about the Psalm 27 app, its place in the Jewish history of technology and the experience of prayer through technology.

Can you reflect on using the Psalm 27 app in preparation for the High Holidays and beyond?

Psalm 27 has a lot of complicated elements. There’s the comfort, there’s the fear, there’s the questioning, there’s a pining for God’s presence. It’s hard to read and take it all in. It’s the kind of thing you have to do over and over again. The app breaks it down. It helps you look at each phrase, or even a word to focus on, so that you can dive into the nuance of each particular piece of it and explore the themes brought up by those phrases and those key words. The app offers a rich and multi-layered experience as you’re preparing for the High Holy Days. It’s also a guide to the user who may not have the training or the patience to sit and read Psalm 27 on their own. It allows them to dive into those themes in a rich and reflective way.

You have the coolest job in all of rabbi-dom! How did you become the director of digital media for CCAR?

The job was created for me. I didn’t think my tech knowledge was so out of the ordinary until I was in Jerusalem studying at Hebrew Union College and the VCR broke. No one knew how to operate the machine, so I ended up fixing it. It became clear that the more time I spent with my classmates, the more my tech knowledge and experience exceeded theirs. So then I leaned into it. I wrote my rabbinical thesis on visual tefillah, which is projecting the prayers during services.

How does technology enhance the prayer experience?

There is a lot of historical antecedence that make it obvious to use screens and technology in prayer. For example, there is art in worship spaces that include frescos, stained glass and mosaics. There’s a long tradition of having beautiful imagery in prayer spaces. We also use our technology tools. The parchment scroll was an invention, which was a successor to carving stone tablets. The printed press was also another innovation. All of these different media contain our sacred texts and have evolved and upgraded over time. It naturally led to using some form of technology and art in prayer settings. But I wanted to take on the app project because I’ve seen examples of it done poorly and I knew it could be done well, intentionally, thoughtfully and prayerfully.

I love what you just said about the historical antecedence to use screens and technology in prayer. Would you call yourself a digital native?

I think I’m an early digital immigrant. I’m the child of a rabbi and an engineer, so my tech leanings were early on. I see myself as a bridge, as having learned technology young enough that I don’t have an accent, so to speak. It enables me to be a bridge between the actual digital natives and digital immigrants who need help managing this new landscape.

How was Rabbi Robbins’s book an ideal candidate on which to base this app, and is this the first book-related app you’ve done for CCAR?

The Psalm 27 app is the first to be based directly on a book. The app’s design and the way a person uses it was intentional. It was meant to create a meditative feel that we wanted users to have to go through the process. Rabbi Robbins’s book guides people through this spiritual meditative practice, which she also uses as a tool for teaching classes. There’s a reading for every day in Elul and Tishrei through Sukkot. However, during Sukkot there’s a specific Shabbat reading. If you’re using the book, the actual reading per day shifts each year. Shabbat falls at a different point, so you have to do some calculations on your own if you’re using the book. One of the benefits of the app is that it does the math for you.

Can you take us through some of the features of the app?

After downloading the app, you open it up and select, “Take me to today’s reading,” and you’re right there. But there are other pieces the app offers that we could never do in a book. There’s beautiful music—a rich variety of styles based on Psalm 27. The music really enhances someone’s practice. Whereas, if someone was following the book, there’s a website where you can hear songs. But now it’s all built into the app.

Starting and then maintaining a spiritual practice is very challenging, so the app offers different ways of making it easier. There’s an alarm to remind you to do the practice every day. There’s a timer built into it, so you don’t have to find a kitchen timer. These little pieces make it easier to engage in this meditative practice that the book lays out very nicely but is limited in how much it can actively guide you every day.

There are also photographs. When Rabbi Robbins started teaching her book’s content, some of her students offered photographs they had taken on the particular themes. We also received photographs from the chief executive of CCAR Press, who has an arts background and is an avid photographer. So, each day, there’s a meditative image to sit with during the meditation period. It wouldn’t be realistic to put them in the book, necessarily, but in the app, it’s accessible. At the end of the last step of the meditation practices, there’s an opportunity to reflect and jot down a few short reminders—things you want to carry with you throughout the day. You can save it as an image and make it your lock screen or your home screen so it’s right there at your fingertips as a reminder.

How does the app feel more personal than the average virtual experience?

You can imagine yourself with other Jews around the world who are reading Psalm 27 before and during the High Holy Days. And now, those Jews are using this app as a guide. Even if you’re using the app on your own versus a group setting, there’s still this knowledge and awareness that you’re also doing it with other people at the same time.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

We have these new technological tools, and it’s up to us to figure out how we can utilize them in beneficial and spiritually enhancing ways, and not have them be distracting or negative. Technology is like any tool—it can be used well or improperly. Part of my work is to figure out how we can incorporate all these new technologies, as we’ve done for the past thousands of years, into Jewish life and practice today.

Find the app for iOS here and for Android here. Find a downloadable study guide here.