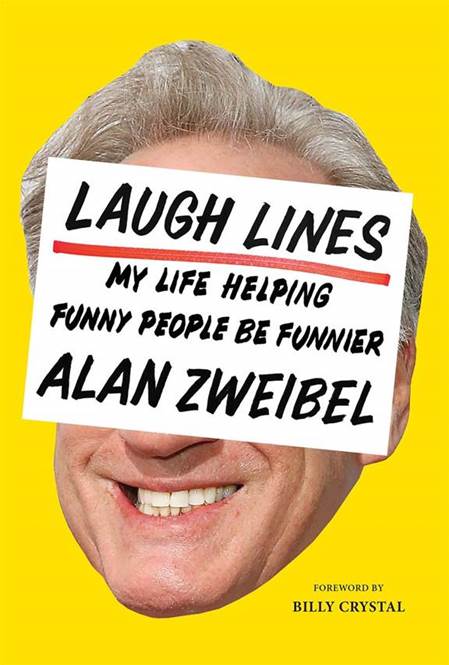

He’s the guy who created Gilda Radner’s immortal Roseanne Roseannadanna. “Weekend Update”? Most of the original punch lines were his. He went on to collaborate with icons like Billy Crystal, Larry David and Garry Shandling. But Alan Zweibel wasn’t always a Tony- and Emmy Award-winning writer. Oh no. He got his start writing jokes for Catskills comics, carpooling with the then-unknown Crystal to comedy clubs and slicing deli meat in Queens, all after failing to get into law school. He talks about all this and more in his new memoir, “Laugh Lines: My Life Helping Funny People Be Funnier.”

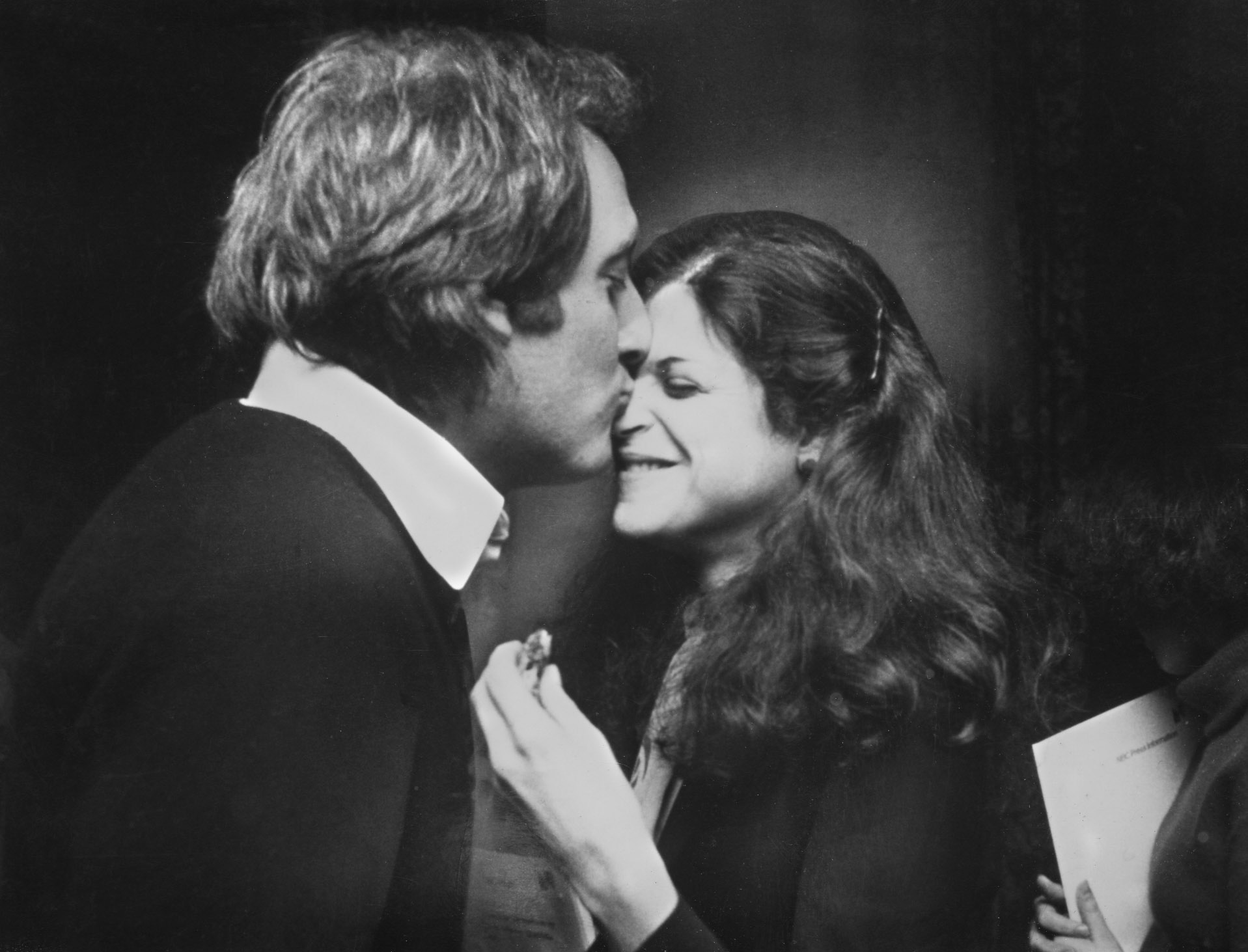

I loved this book. But I first was introduced to your work with “Bunny Bunny,” the story of your friendship with Gilda Radner years ago. It was hilarious. You had the funniest line that I still think about. You would’ve dated Gilda, but nobody would be good enough for your parents. Your parents are still mad at you that you didn’t marry your sister.

Oh. That’s nice. Thank you.

You seem like you had a fairly happy, well-adjusted childhood. And you can tell me if I’m wrong on this, but I get the sense that a lot of comedians grow up and they’re made fun of, or they’re tortured or they have some sort of tumultuous baggage-laden past. You seem like a pretty well-adjusted person.

Well, you know something, that’s a very, very fair assessment of it. I was the oldest of four kids, and we grew up on Long Island, and it was a typical suburban neighborhood back then. And I didn’t realize how dysfunctional it was until many years later! So, while I was experiencing it, I had the greatest childhood in the world.

When you look back, what was dysfunctional about it? Or what was unusual about it, in retrospect?

Well, I had a mother like you just quoted from that book. So, it was your typical suburban, Jewish family that moved to the suburbs. Their parents had come here in search of the American Dream from Europe, and this was the first generation that was able to get out of the tenements and the ghettos of New York, the Lower East Side, and move to suburbia, and it was idyllic. It was the ’60s. It was first Eisenhower, and then Kennedy, and all that stuff. They had something that their parents didn’t have: leisure time. And so it was fun; it was fun back then. It was ice cream, riding your bike around the neighborhood after dark and everything was OK.

So, when I say dysfunctional, that’s an often-used word, and I don’t want to disregard it, because my parents were great and all of that. But it’s the foibles and it’s the…some of the idiosyncrasies that you pick up and you don’t realize that that’s what it is when you’re going through it. You think that’s the way everybody is living. And it’s later on when you go, “Alright. So we were kosher in the house….”

But you ate in the garage sometimes!

We ordered from the Chinese restaurant and ate it in the garage, because we didn’t live in the garage. That was the car’s house. That’s awfully weird, manipulative thinking. So it’s usually with the benefit of hindsight that you go, “I’m not gonna do that.”

What do you think it is about Brooklyn and Long Island that produces comedians? I’m thinking of Jerry Seinfeld, I’m thinking of your friend Billy Crystal, I’m thinking of Larry David, Woody Allen, these people who come from the same geographic area and somewhat similar background. What lends itself to comedy?

You know something? It’s a wonderful question. Carol Leifer is from there. Eddie Murphy is from there. I’m trying to remember where Paul Reiser is from. If I’m able to identify why, I’m the smartest man around, OK? But I do think there was a culture that we were all brought up with. We all basically have the same backgrounds. Once again, the immigrants, they came here, and here was the promised land. And I think we looked at the world maybe a little bit differently. We were sort of privileged, you know what I mean? But still middle-class, so we had the luxury of that. We all grew up with the same comedy albums, whether it was “2,000-Year-Old Man,” Vaughn Meader’s “The First Family,” Allan Sherman singing all these fun songs and everything. I can’t help but think we had the luxury of sitting back and going, “There’s something a little askew here.” You know, Alan King said what everybody’s father said at the dinner table.

You were sort of one generation up from that struggle. They got up, they moved to Brooklyn, then they moved to Long Island. You were the product of this middle-class family, and then what happened? You didn’t get into law school.

Look, I always wanted to be a comedy writer, and I joke about the law boards. I always wanted to be a comedy writer from the age at 12, when the old “The Dick Van Dyke Show” came on the air; it looked like a life I wanted to have. Get married to Mary Tyler Moore, you’ve got a kid, you have a nice house in New Rochelle and you spend your days at work, lying on a couch and joking around with Buddy and Sal. Who wouldn’t like that? But I didn’t know how to become a comedy writer; nobody did. There were not that many film schools. There certainly was no internet. I didn’t know how to go about doing it; there was no prescribed course. So I applied to law schools; as the generation before me would say, “So you had something to fall back on.”

And the law schools looked at my law boards, and they went, “No, no, no, you’re not gonna fall back on us. You’re gonna spring forward. You’re gonna do whatever you wanna do, but not here.” It was the best thing that ever happened to me. That and my parents going to Lake Tahoe.

Right, and your mother slipped your info to the comedian Morty Gunty.

She didn’t slip anything to him. That sounds incredibly lewd. She mentioned that I wanted to be a comedy writer. Well, actually, he slipped her his name and phone number, and I called it, and I started writing for him and for other comedians who at the time were working in the Catskill Mountains.

Was there any pushback from your parents? Any, “What are you doing with your life? What’s going on? Go to law school!” What was their reaction?

Never, never, never, never. My father used to wake up and wait up for me when I’d come back. He would be waiting up for me and make me breakfast and ask me, “OK, which jokes worked? Which didn’t?” They could not have been more supportive. There was not an ounce, even for one second, of pushback.

So, you start doing your own stand-up and you get discovered for “Saturday Night Live” by Lorne Michaels after doing an atrocious comedy set, right? And he says, “You’re the worst comedian I’ve never seen, but I love your jokes.” Right?

Well, he liked my material and wanted to see more of it. I met with Lorne, and I came in with a binder that had about 1,100 jokes that I had typed up in it. And I had my meeting with him, and I was really nervous. He opened the binder, read the first joke and nodded.

He said, “Very good.” And I left the binder with him. To this day, he’s the smartest guy in the world, and he can look at one joke and see the construction, see the sensibility, see the mindset and see if this was somebody he wanted to contribute it to this new show. He had called it, the very first meeting, “The Comedy Variety Show,” but went on to elaborate that it’s a variety of different kinds of comedy. And, if you looked around the writers’ room, or around the actors, everyone came from different disciplines. Some were Second City, Mike [O’Donoghue] did National Lampoon, and I was writing jokes for Catskills comedians. Tom Schiller made documentaries. Everybody had their own niche and approached the world from their own little direction. It was a variety of different kinds of comedy.

You started out in 1975, writing for these people who were with “Saturday Night Live” during this golden age, which subsequently become kind of mythologized. You always hear, “Oh, Chevy Chase is the difficult one. John Belushi was the volatile one, and Gilda was the sweet, lovable one and Jane was the one who went home to her family and her dog.” Did everybody seem as though they were all on equal footing? When did it start to become bigger than just these anonymous people who lucked into the show? At what point did you start to feel like, well, we’re bigger than something other than ourselves?

That’s a good question. Look, when everyone started, nobody was saying this. Lorne said, “Let’s make each other laugh, and if we make each other laugh, we’ll put it on television.” And there was a certain anonymity. Then I remember one day that Gilda came in, she and Belushi had taken the subway. They both lived downtown in Greenwich Village and had taken the subway to the offices at 30 Rock, because I guess it was snowing and he couldn’t get a cab or whatever. I remember Gilda saying to me, “I can’t take the subway anymore. Me and Belushi got mobbed.” I remember going into Carnegie Hall with Gilda, and this was a pretty sophisticated place. You know, it’s Carnegie Hall, for God’s sake. We went in and we heard, it’s got five tiers, and we heard from the upper balconies, “Hey, Roseanne Roseannadanna! Hey, Gilda!”

I helped to executive produce a documentary—my wife and I co-produced it—last year called “Love, Gilda,” about Gilda’s life. There’s one clip there of Bill Murray doing an interview, saying, “All of a sudden we came back one summer and we were famous.” I think that when it happened, it really happened. It’s a little off-putting, but when it happened it pretty much turned on a dime at that point.

Who were the best hosts?

Buck Henry, Steve Martin, Candice Bergen, Lily [Tomlin]. That’s no special order, but for me it was Buck Henry. He became my friend and mentor, and I just liked his understated sense of humor. I thought he was great. Steve Martin is hilarious, Lily is Lily and Candice Bergen. This was well before “Murphy Brown” and she was just, what a great actress. So there were people when you saw their names on the board as upcoming hosts, you went, “Yay!”

Obviously, the show has continued on for years and years. Are there certain seasons that you just think, “What were they doing?” And other seasons you think were wonderful?

I’ve never felt that. You’ve gotta understand that “SNL,” yeah, it had some years where they were reconstituting the cast. And you go, “But they’ve been on so long.” When they went with new players and new writers, they were shifting gears in front of us on live television. And all of a sudden, wow, Adam Sandler, wow, Tina Fey, Jon Lovitz, Amy Poehler. Somebody comes along like Kate McKinnon, for God’s sake, she’s like a gift from God. So even when it seemed to be lean, and they were going through a couple of rough patches, I in the very least always applauded how daring it was. And there was nothing else like it on television. So, no, I remained a devotee of it since I left.

You went on to movies and Los Angeles. Roger Ebert panned your film “North.” This experience is in the book. Can you describe in your own words what happened when you later met him? He was in a restaurant, wearing a horrible mustard yellow sweater, right?

I was on a book tour, and I was in a restaurant in Chicago. People had taken me out to lunch, and I always wondered what it would be like if I ever ran into Roger Ebert. I just didn’t know if our paths would ever cross. And this was about 10 years later; it was a book I had called “The Other Shulman,” which won the Thurber Prize. So it was pretty well-heralded, and I was feeling pretty good. And I’m in Chicago on tour. And Roger Ebert is at a table, a few tables away at the same restaurant. And I looked over, and I always wondered what it’d be like, what I would say, what I would do. And I remember, he was wearing this ridiculous-looking sweater, oversized, with colors like burnt orange and puke green. It was awful.

And at one point, he got up and went to the men’s room, and I excused myself from the table and followed him, not knowing at all what I was going to do when I caught up with him. I was just praying there wouldn’t be any bloodshed. I had no idea what I was going to do. And we’re in the men’s room now, and we’re washing our hands afterward at adjoining sinks. And so I looked up, and it’s in the mirror, and I said, “Roger?” And he looked up, and you could see he was trying to place me. Anyway, I went, “Alan Zweibel.” And the blood drained from his face.

He turned. And I said, “Roger, I just gotta tell you that I hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate that sweater you’re wearing”— which was a quote straight from his [review]. And he smiled a little, and I smiled a lot and that let him know that everything was OK. Then he started laughing, and I started laughing. We shook hands. I’m glad I ran into him.

What was it like to collaborate with Billy Crystal, your long-time friend, on the play “700 Sundays”?

Billy and I were good friends. We started out together in 1974. He lived in Long Beach, Long Island. I lived in Woodmere, Long Island, which is only four or five towns over. We became friends. He used to pick me up in his little blue Volkswagen. He drove me into the city. We did our jokes, and then we would drive back and listen to the cassettes and critique each other in the car. That’s how we started. I got “SNL,” and he eventually went to California. He did “Soap” and the groundbreaking role of Jodie.

Through all the years, we never worked with each other. We were friends. And it ends up that Rob Reiner had started a movie production company called Castle Rock. And as fate would have it, I’m sharing a suite with Billy and Larry David, my two oldest friends.

I’m working on a script of a movie I did that Rob also directed called “The Story of Us.” Billy stuck his head into the office and said, “Can I talk to you for a minute?” I follow and he says, “Look, I’m thinking of writing a one-man show, a Broadway show about my family, if you want to collaborate with me?” And I said, “You bet. Absolutely.”

And, for those of your readers who don’t know what it means, Billy’s father worked two, three jobs at that time and worked six days a week, and Sunday was his day off. Sunday was the day he had to spend with his dad, the beach, the boardwalk, at Yankee games, whatever. His father died suddenly, so Billy once calculated that he had roughly 700 Sundays with him.

I started collaborating with him on it, and it was a very, very interesting situation that I embraced. I was really struck by and touched that my best friend would trust me with his family to write and put words into the mouths of his family members.

It was a wonderful dance that we developed, and it won a Tony. It was the kind of show where people saw the ads of Billy Crystal coming to Broadway in a one-man show, thinking they’d laugh at Billy Crystal for two hours, not knowing that at intermission or after the show, the parents would call their children or children would call the parent.

In this era of Twitter, when you can become famous with a tweet or on YouTube, what do you think of comedy now?

The fact is I think that right now there’s an over-glut of the Trump stuff. And it doesn’t matter which side of the aisle you sit on, whether you’re Republican or Democrat. I think people are just now outraged, and it’s a venting of anger. They’re appalled. I think there’s a personality thing there. That being said, with the internet, on the one hand it’s more convenient. You don’t have to pass around the resume. You can just do something and upload it and there’s your audition. On the other hand, before, it was a screening process. So I think it’s a little harder in some respects to wade through all of the thousands and thousands of things that people have put on there. You know what I’m saying? But, ultimately, I think it’s good. And ultimately, the cream will rise to the top.

I’m not afraid to say it: I am a fan as well as a journalist. And I happen to know you’ve been married for many years, and you have three kids. And Billy Crystal has been married for many years and to the same person. How?

That’s a good question. That’s a wonderful question. And to compare me and Billy is a very, very, apt thing to say, Robin and I just celebrated our 40th anniversary in November. We have three children and five grand-children. Billy and Janice will be celebrating their 50th anniversary come June. They have two daughters and four grand-children.

I think that, for me, I can’t speak for Billy, but for me, I came from the family I described at the beginning. I knew I always wanted to have children. My dad was a great dad. I wanted those things; I wanted children. And, well, let’s put it this way: When we were married about three, four months, Robin and I, I said to her, “Listen, I love you and everything, but God forbid you die before I do, where do we keep the hammer?” I’ve married somebody who knows where the hammer is. It’s the luxury of being the artist. I am going into my office every day and just roaming the landscape of whatever the imagination is, to put words together and to try to make it work. And she has made that as comfortable and as supportive as my parents were. My wife is that way and I’m really lucky. And, in the case of Billy, I think he would say the same thing about his situation.

In closing, could you talk a little bit about your sister? You dedicated the book to her.

Yeah, I was the oldest of four; Fran came next, then Barbara, then David. And Fran was two years younger than me. We were friends. It was the kind of thing [when] we were really little, we shared a bedroom. When we got older, in high school, we hung out in the same crowd and dated each other’s friends and whatever, and we were pals. And when I was first starting out, even growing up, I loved making her laugh. She had an infectious laugh, and she wasn’t phony about it. There was something in the way she gave into the laugh. When I first started doing what I was doing, the comedy stuff, I would read the jokes to her before I sent them to the Catskill guys, and she would laugh. Even if they don’t buy it, I know it’s funny, ‘cause Fran laughed.

I had a really shitty show on the air called “Good Sports,” and she told me that that show never made her laugh. Fran was a good barometer to me. To an incredible extent, to this very day, I go, “Would this make Fran laugh?” This is my way of saying, “Hi, you’re still with me. I love you.”