Myra Sack and her husband, Matt Goldstein, did everything right: They got screened for Jewish genetic diseases before conceiving their daughter, Havi, who was born strong and presumably healthy on the couple’s second wedding anniversary. While Myra was a Tay-Sachs carrier, Matt was not—or so they believed. However, as Havi failed to progress, the family sought answers. Due to an error, it turned out that Matt was, in fact, a carrier. Havi’s apparent deterioration was due to Tay-Sachs, and the diagnosis was fatal.

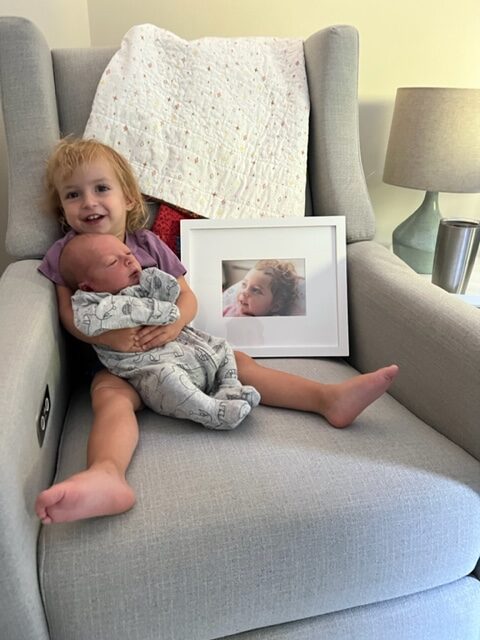

Havi died at 2 years, 4 months and 16 days old. Myra and Matt live in Jamaica Plain with their two kids, Kaia and Ezra; Myra is working on a memoir about the experience. (You can read more of her story here. She’s a phenomenal writer.)

September is Tay-Sachs Awareness Month. This week, I talked to Myra about her faith, her loss and how to navigate the unthinkable.

Could you give me just a bit of background on your family?

Our family origin story is that my husband, Matt, and I met through one of my best friends and former soccer teammates at Dartmouth College. Matt and I met in 2006, when I was a freshman at Dartmouth, and he was dropping his sister off at college. We ended up getting married in 2016 on Sept. 4, sort of near Dartmouth, which became a place that we considered home.

We landed in Boston as transplants, actually, because Matt started his residency in internal medicine at the Brigham. We knew we wanted to start a family, and we also knew that we were both Ashkenazi Jewish. This necessitated preconception genetic screening, because we both knew that we were at risk for some pretty horrible diseases. So I underwent preconception genetic screening in 2017 and learned that I was a Tay-Sachs carrier. I was finishing up a business school in the evenings over at BU when I got the call.

Related

For those who might not know: What’s the genetic screening process? How do you know what to test for and what to do?

For us, my husband was in medicine. We’re both Ashkenazi Jewish. Genetic testing was part of what we understood to be the standard process for starting a family. I think that I initiated a preconception genetic appointment before anyone in the medical system did. I scheduled an appointment with my OB, and then the OB walked me through the options for what that screening could look like, based on our background.

We got blood work done. Because I was a carrier, I got a phone call from a nurse who told me. If Matt was thought to be a carrier, then genetic counseling would have gotten involved.

Were you scared to get tested?

When I got my results back and learned I was a carrier, I was terrified. Going into the experience, I was maybe naively optimistic, but I also think I was sort of anxious about this idea that you could be screened for everything. You learn all sorts of things.

Havi was born on your anniversary.

Yes. She was beautiful, insanely gorgeous eyes. I remember the nurse, when she put her on my chest, Havi lifted her neck and the nurse said, “Wow, she’s so strong!”

So, basically, for the first year of her life, we lived as a new family of three. That first year was both incredible and exhausting, and all the things that come with being a new parent.

But at about one year, we started to notice that Havi wasn’t progressing in the way that she should. And so her pediatrician referred us to neurology at Boston Children’s, as well as early intervention. This kicked off several months’ worth of sessions where Havi was doing physical therapy and occupational therapy. We were doing everything we could to get her stronger. And then three months later, at 15 months, we got this fatal Tay-Sachs diagnosis, which obviously took us both by incredible surprise, given the testing that we had undergone.

How was Havi diagnosed?

At our first neurology appointment, the pediatric neurologist said: “I see thousands of kids who are sick, and Havi is not one of them. She’s just slowly getting there. So go home and enjoy her.”

Then we went to another neurologist, several months after she began her early intervention, and she just wasn’t progressing. In fact, we were starting to see some regression in terms of her motor skills. She went from having incredibly beautiful posture to slouching when she was sitting. That neurologist diagnosed her with cerebral palsy. “You didn’t have a traumatic birth experience, so we should get Havi an MRI because we’re seeing more and more cerebral palsy cases that are genetically associated.”

So we were referred to a neuro-geneticist—our third neurologist—who was going to be the person whom we saw just before Havi went in for her MRI for a clinical exam. It was this neurologist who noticed Havi startle, which is characteristic of Tay-Sachs. He asked us about our genetic testing. We laughed, “Whatever’s going on, it’s not Tay-Sachs!” But he said, “Based on this exam, and based on what I’m seeing, I’d like her to be tested.” So that was the moment at which fear crept in.

You gathered for Havi’s “Shabbirthday” shortly after the diagnosis. What was that like? What was the cycle of emotions between the emotions and then gathering in a meaningful way?

I think that during Havi’s diagnostic odyssey, there was incredible stress, anxiety, fear and worry—this constant worry that we weren’t doing everything we could as parents to get her to where she needed to be. During the diagnostic odyssey, we were open to anything and everything that would help our child; I think any parent does whatever it takes to make sure that their child is OK.

When we got the Tay-Sachs diagnosis, we were shocked and horrified. It’s so unimaginable that you learn that your 15-month-old who you think is perfect and going to live a long life is going to die before she’s three years old. I think the emotional anesthetics kick in and, in some ways, your body protects itself and is numb. It was a combination of numb and devastated.

Psychologically, I think maybe it’s an opportunity to be braver than you realize you could be because you’re existing in this liminal space that forces you to operate in a gear that you wish you never had to. It was getting to that place that we realized that we could count the number of days that Havi had left.

Basically, we decided that she was just going to be held and loved with people who could appreciate how sacred she was, who could see her as sacred and not sick. And that was our operating principle. It ended up saving our lives and our marriage, sort of leaning into the pain as opposed to keeping it at bay.

That’s actually an interesting side note, and I think it’s important. How did it affect your partnership?

We had an incredible amount of shared pain and shared love, because we were the only other person who was really experiencing this at the depth. It actually ended up bringing us closer, if that was possible, and making our marriage stronger. I think that was because we decided that together that we were going to honor our daughter as fully as we could. Once we got aligned on that basic principle, we knew that we needed each other. Every morning, we’d ask the other person: “What do you need today to be OK?” And we still ask each other that every day.

How did you interact with people who wanted to help but didn’t know how?

A family friend from Philadelphia actually sent us a book called “Bearing the Unbearable,” which was written by Dr. Joanne Cacciatore. She’s a grief counselor and a professor. Several people had sent us books on grief and loss. We opened them and promptly closed them. This was the first book that I really felt like was a refuge for me…I made it required reading for everyone in our orbit.

That book helped people understand that this wasn’t going to be something we were going to get over. This wasn’t something that was a part of God’s plan. Havi wasn’t going to be in a better place. It wasn’t OK because we could have other children. And so it was really a guide for what not to say.

Sometimes our society sends us messages that we just need to be strong or resilient. And really, what we need is to feel everything we’re feeling and let that be OK.…I think when you have people in your life who can validate what you’re feeling, then you have the courage and the strength to reject messages that sort of insult your soul. And that’s what we learned to do.

Was there anything in your Jewish faith that helped you?

After Havi died, I spent every other week talking to a rabbi from Philadelphia from my hometown, who started her own congregation called Or Zarua. Her name is Rabbi Shelley Barnathan; she has known me since I was a child. She and I had biweekly Zoom calls, where she just created a space for me to really explore what it means when you lose someone, because all of a sudden, any notion of the afterlife is turned upside down when it’s your child and when you know exactly what’s happened. Her wisdom and her vulnerability was probably the most helpful and comforting connection to Judaism for me in this process.

Let’s come to the to the present. You now have other children. How did you deal with this, genetically?

I was 11 weeks pregnant with Kaia when we got Havi’s diagnosis. The same day we got her diagnosis, I was in high-risk OB getting a chorionic villus sample done. Then we waited three weeks to learn that Kaia was not affected with Tay-Sachs. That was a beautiful gift at an incredibly impossible time.

With Ezra, who’s three-and-a-half weeks old, we pursued IVF. We did that because we just couldn’t stomach the thought of terminating a child. We knew how horrifying the disease itself was. So we leaned into the magic of modern medicine and now have Ezra. They can biopsy the embryos and test embryos for different diseases. In our case, they were able to do targeted testing of the embryo for Tay-Sachs.

What would you like people reading this to take away from your experience? It seems like you guys did everything medically right, and there was still just a twist in your story.

Getting screened is important, and having a relationship with someone in the medical system whom you trust and whom you feel like you can really ask all of the questions that you need to. I think genetic counseling is essential, and making sure that the visit is comprehensive, and that you’re not afraid to ask any questions is so important on the preventative side. Then I think, in the wake of just incredible loss, what I would urge people to embrace is that there’s a way to show up for people that is life-sustaining—that looks like honoring and integrating the people that they’ve lost, instead of casting them aside or being afraid to name them.

This was a loss that was so transformative. How will it change the way that you parent?

We laugh a lot. And I think that’s something that Havi taught us: What seems to be a big stressor is actually maybe trivial. Find moments to laugh and experience joy more often. We don’t take a single monkey bar for granted at the park now.