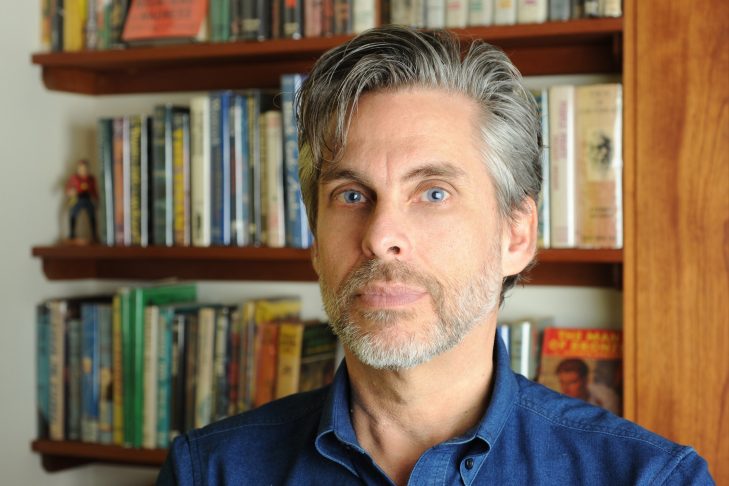

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Michael Chabon was in Brookline this week to promote his new novel, “Moonglow.” His appearance in front of a packed crowd at the Coolidge Corner Theatre coincided with the beginning of Jewish Book Month. The annual event celebrating Jewish literature is observed during the month preceding Hanukkah, which this year falls on Saturday, Dec. 24.

“Moonglow” is a fictional family saga containing elements of a literary memoir that tantalizes readers. Calling the book a novel, yet referring to it in an author’s note as a memoir, reinforces that conceit. By the time the acknowledgements come around, Chabon has conceded that the book is a “pack of lies.” That kind of teasing led one reviewer in The New York Times to declare that, “Whatever else it is—a novel, a memoir, a pack of lies, a mishmash—this book is beautiful.”

At the Q&A that followed his reading, Chabon mentioned that “Moonglow” was inspired by a visit to his dying grandfather in 1989. But he kept the audience at arms-length about the book’s genre. He insisted it was fiction rooted in family stories. One such story is the basis of the dramatic scene that opens the book. The narrator’s grandfather, who remains unnamed, is attempting to strangle his boss. It’s the 1950s and he has just been fired from his job as a salesman so that Alger Hiss, the accused Soviet spy, can take his place.

It’s just one of many deathbed stories in the book that this grandfather conveys to his grandson, also named Michael Chabon. The stories are glorious, depicting Chabon’s grandparents’ unconventional courtship, tales of World War II, a picaresque journey to find Wernher von Braun, the German rocket scientist who was the father of America’s rocket program, and misadventures in a South Florida retirement community where Chabon’s now-widowed grandfather hunts down a python that has been eating the pets. For all of its madcap storylines, the reader quickly discerns that at its core, the book’s internal logic and idiosyncratic structure are held together by the trauma of the Holocaust. The grandmother of Chabon, the character, is a Holocaust survivor whose insanity hovers over the book’s events.

Echoes of World War II and its attendant Jewish themes are also prominent in previous works that include “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay” and “The Yiddish Policemen’s Union.” The first drew on Chabon’s fascination with New York of the 1930s and 40s, as well as his obsession with comic books. The latter, which told the story of a Jewish homeland relocated to Alaska, is perhaps Chabon’s most controversial Jewish book to date. At the Coolidge Corner Theatre he noted: “I knew there would be a possible reading of [“The Yiddish Policemen’s Union”] that would be some kind of analogy for the state of Israel. I felt it. Some critics said it was a Zionist work; some said it was an anti-Zionist work. The Zionist camp said this is a fantasy of Israel’s destruction. The anti-Zionists said it was clear I was writing a cautionary tale about how it would be if there was no Israel. I’m happy with both of those interpretations. I didn’t choose either. I wouldn’t set out writing a book with any kind of political agenda. But it was sort of gratifying to be attacked from both sides.”

“Moonglow” may be masquerading as a literary memoir, but in the end it is intent on exploring the idea of what constitutes bedrock truth. “One of the many things about the book,” said Chabon, “is the way news gets generated in families and how the official version of what happens is established. The truth in families is a slippery thing, and that’s a strong motif in this book.”

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE