Ariel Burger first shook Elie Wiesel’s hand when he was 15 years old. As a young man, he came to have an intellectual and personal relationship with the Nobel Prize winner and Holocaust survivor. As a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University, Burger was Wiesel’s teaching assistant for seven years.

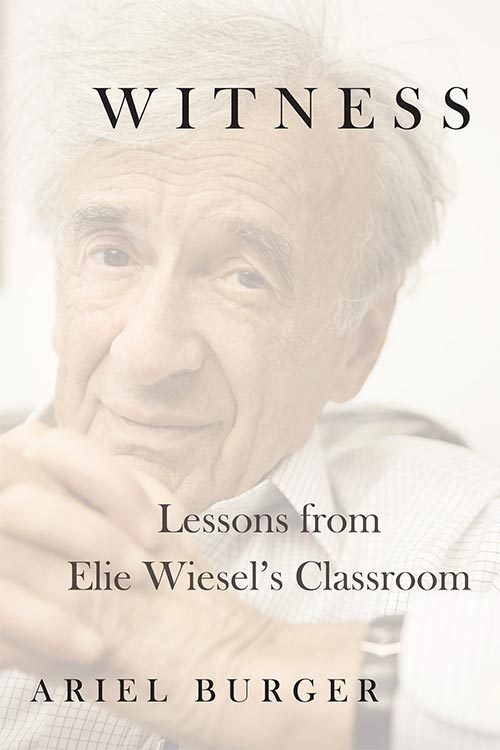

In his new book, “Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom,” Burger vividly situates the reader inside Wiesel’s classroom. He shares details of the thought-provoking lectures as well as the heartfelt questions with which Wiesel challenged his students. Burger recently spoke with JewishBoston about his mentor and how Wiesel shaped his life.

How did you effectively place the reader directly in Elie Wiesel’s classroom?

The main purpose of the book was to give the reader the experience of being in Elie Weisel’s classroom. I took notes for all the years I was in his classroom as a teaching assistant. I based the book on those notes, my journal entries and the one-on-one meetings I had with him. I recorded voice memos after those meetings. I didn’t want to forget anything he said.

As I sat in class as his teaching assistant, I also paid attention to the content of the lessons and gave equal attention to the form he was using. I would think, how did he just link an ancient Eastern text to a modern French novel and then to contemporary events in a seamless way? He never crafted lectures but employed the Socratic method. The questions he asked emerged from a classroom conversation. Many times, he created a dialogue between students with opposing opinions.

When did you meet Wiesel?

I met him when I was 15. My stepfather was a conductor who worked with Elie Wiesel on a musical performance, and he introduced me to him after a lecture he gave at the 92nd Street Y. At the time, I was in a complicated place with my relationship to Judaism and my parents, and the relationship between my Orthodox Jewish life and my life as an artist. I was drawn to Elie Wiesel as someone who had perspective on those issues.

Over the next six years, I spent time in Israel, and I would write to him or meet with him when he came to Jerusalem. I asked questions about religious life and faith and doubt. I asked him how to be a modern person in touch with Jewish roots. I had questions about art and career, and questions about creating a dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians.

I became his teaching assistant in 2003 and met with him every week. We became a lot closer in those years. When I graduated, our relationship shifted from that of a teacher with whom I was in awe to that of a mentor and real friend.

You talk about many works of literature that you explored with Wiesel. What are some of your favorites?

One of the greatest highlights for me was the juxtaposition between different kinds of texts. For example, Wiesel pointed out the juxtaposition between the Book of Genesis and a relatively recent book by Philip Gourevitch about the genocide in Rwanda. It was a very powerful connection between the two texts, and it had tremendous repercussions on how I looked at Genesis and the Bible itself.

I also loved reading Kafka with Wiesel. He had a very intimate sense of Kafka and his story, almost as if he had lived it. We studied the story of the Binding of Isaac and juxtaposed it with “Fear and Trembling” by Kierkegaard. Among the things most new to me were reading plays. I hadn’t read plays in a serious way. We read Brecht, Arthur Miller and Archibald MacLeish. We also read several books—fiction and non-fiction—that emerged from specific instances of oppression and genocide.

Why do you think the Book of Job was Wiesel’s favorite book of the Bible?

For Elie Wiesel, who as a child and teenager lost members of his family and suffered the destruction of the world he had grown up in, Job is the book that most directly responds to that kind of unimaginable human experience. And it does so without providing neat answers. When God finally appears in the Book of Job out of the whirlwind, God doesn’t answer questions at all. That made the Book of Job frustrating for many readers—the lack of resolution, the lack of neat, tidy answers. I think that made the book special and sacred to Elie Wiesel. It is one of the texts in our canon that challenges every notion we have about simple answers in religious life.

How do you draw inspiration from Elie Wiesel about what’s happening in today’s world?

Elie Wiesel said when you see the rise of hate, you have to fight it right away. It’s like a disease that spreads, and silence allows it to spread. Don’t hesitate; act right away. Although he insisted the Holocaust was unique—nothing could be compared to it—he nevertheless drew universal lessons from it. That’s what drove him to stand up for people in Cambodia, Yugoslavia and other places. When we confront hatred, a lot of times our response is thoughtful and heady, but we have to fight fire with a better fire that heals instead of burns. He would encourage us to stand up against hatred and evil and to do it with a lot of passion. In longing for a better world, we have to allow our hearts to stay open.