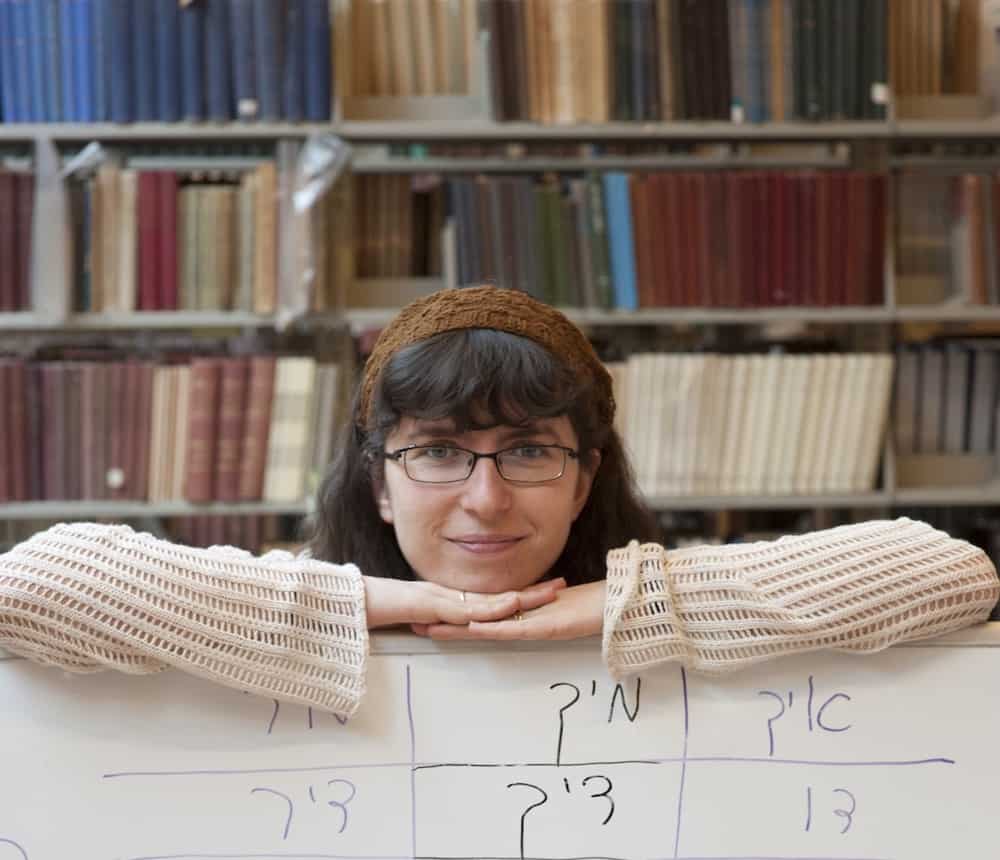

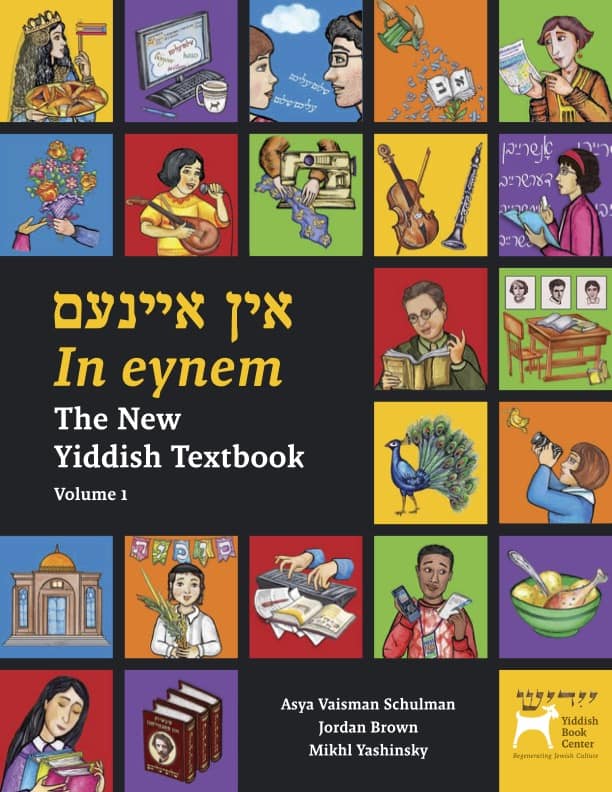

Asya Vaisman Schulman directs the Yiddish Language Institute and the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program at the Yiddish Book Center. She has been affiliated with the Center for over a decade, initially as a fellow and now as a faculty member. In that time, Schulman co-authored the textbook “In eynem: The New Yiddish Textbook” (“together” in Yiddish)—the first textbook to emphasize the “communicative” approach to learning Yiddish. Schulman told JewishBoston that, when learning a language, conjugating verbs and translating passages takes a backseat to communicating directly with another person and culture.

Schulman said that since arriving at the Center, she has “created materials reflecting language as a communication tool.” Before joining the Center, Schulman taught Yiddish at Indiana, Harvard and Columbia Universities, the New York Workmen’s Circle and Gann Academy in Waltham. She was the first student at Barnard College to major in Yiddish studies and went on to earn her Ph.D. in Yiddish from Harvard University.

When did you begin to study Yiddish?

My family moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, from Russia. I grew up knowing Yiddish was important to my Jewish identity. I wasn’t fluent in the language, but I listened to Yiddish music and heard Yiddish phrases. I took small group lessons in high school with a Yiddish teacher who lived near us, and I went to summer programs at YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and Columbia University. My parents created the first major Yiddish website, The Virtual Shtetl. I created the kids’ pages for the website. And I’ve always loved languages—French was my favorite subject, and I wanted to be a French teacher in middle school and high school. I’ve also studied Hebrew and German.

Your family has spoken Yiddish continuously for over 1,000 years. How did that influence you?

For many Jews, especially in America, there is a gap of a few generations in consistently speaking Yiddish. Maybe the great-grandparents spoke Yiddish, but they did not pass it on. There wasn’t a notable gap in my family—three of my four grandparents were Yiddish speakers. My father understands the language and is somewhat fluent. When I studied Yiddish, there was only a brief intermission beforehand. So, it wasn’t this rupture that many families have.

You and your husband exclusively speak Yiddish with your daughter. What led you to make that decision?

My husband and I are Yiddish speakers, so it wasn’t a very difficult decision, but he is doing the hard work. He speaks Yiddish exclusively to our daughter, and she is fully bilingual. At this point, she’s trilingual because we live in Montreal, and she speaks French in school. It’s wonderful to give a child the gift of language at an early age.

Where does your daughter speak Yiddish?

Her interaction has been mostly with Yiddish culture. My husband was the director of KlezKanada, and she grew up in that community of musicians. Last summer at the KlezKanada retreat, she sat with people and spoke Yiddish. Some of them were my former students; she chatted in Yiddish at meals with these young people. It was lovely.

When I think of opportunities to speak Yiddish, I think of Hasidic communities who almost always speak Yiddish exclusively.

There’s a different dialect in those communities, and it’s a different social situation. Although, here in Montreal, the boundaries are more fluid than, for example, in New York. We like to tell the story of my husband and daughter speaking Yiddish at Cheskie’s, the famous Hasidic bakery in Montreal. The baker overheard them speaking Yiddish and was very excited. Since their appearance does not match with speaking Yiddish, he asked them where they were from and how they knew Yiddish, then he gave my daughter a free box of cookies for her nice Yiddish. It’s a great story of positive reinforcement.

As the director of the Yiddish Language Institute and the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program at the Yiddish Book Center, you teach Yiddish as an immersive experience.

I came to the Institute ten years ago to offer an immersive experience. The Steiner Summer Yiddish Program is a major program that is our summer intensive for college students and young adults. It’s a fully immersive cultural program offering daily language classes, song workshops, dance classes and a culture course encompassing literature and history. In addition, we visit Yiddish cultural institutions in New York and have offered a Yiddish theater program.

A language is part of a larger culture, and to understand Yiddish, you must engage with all its components. So, for all our language programs, we include non-optional dance workshops. You don’t have to be a dancer to practice Yiddish dance; however, if you read a dance scene in Yiddish literature, you’ve embodied that experience and understand what you’re reading.

What online resources have you included in “In eynem”’s companion website?

Our website includes multimedia material referred to in the book. Anytime we have an audio or video exercise or a higher resolution image for which there are exercises in the book, those materials are available on the website. When we excerpt a piece of text—whether it’s literary, a snippet from a movie or a clip from an audio program—we include links to the full text for a student to engage. There are also interactive exercises for extra practice, flashcards and image maps. The website’s other major component is a teacher’s guide, which gives detailed lesson plans for implementing the materials.

How old is Yiddish?

Yiddish is over 1,000 years old. Initially, it was mostly a dialect of German (originating from the Rhineland in Germany) written in the Hebrew alphabet with Hebrew words for Jewish concepts. It contains a large component of Luschen-Koidesch, the holy language, a biblical Hebrew Aramaic. Before Yiddish was a distinct language, there was Judeo-German, just like other Judeo languages such as Ladino, which is Judeo-Spanish. There are also Judeo-Aramaic and Judeo-Arabic.

What are some of Yiddish’s language influences?

Over time, Yiddish became more distinct from German as Jews moved around and absorbed additional dialects. There was also a romance component in Yiddish from migrations in Italy and France. The romance component is small, but it’s there. Then as Jews migrated eastwards towards Slavic lands, Yiddish picked up a substantial Slavic component in its vocabulary and grammar. From there, it spread all over the world to the Americas, Australia and South Africa, then back to Western Europe. Yiddish dialects absorbed elements of surrounding languages as they continued to develop.

It’s an exciting time to be immersed in Yiddish. Is it fair to say we’re amid a Yiddish revival?

The Yiddish revival has been happening for decades. It’s a continuous process. There was the Klezmer revival in the ’70s, where that music became more popular. But Yiddish has always been there. It’s just a question of how much it’s in the public eye at any given moment and whether widespread attention has been paid to it. There have also been external factors such as immigration and the Holocaust that affected the number of Yiddish speakers. But interest in Yiddish and speakers of Yiddish has been consistent throughout time.

Where can people find out about the Book Center’s Yiddish language programs?

People can register on our website. There’s also an FAQ section in which questions such as whether you need to know the Yiddish alphabet (familiarity with it is recommended) and how to purchase the “In eynem” textbook are answered.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.