How do we talk to our youngest kids about Juneteenth, especially now that it’s a formalized holiday? What’s the most age-appropriate framing? For answers, I talked to two elementary teachers at Watertown’s JCDS, Boston’s Jewish Community Day School. Naomi Greenfield is a second grade teacher at JCDS, and Nikki Cohen teaches first grade. The pair worked together on a variety of Juneteenth lessons. If you’re wondering how to talk about Juneteenth with your kids, they have ideas.

What do you think young children are capable of understanding about Juneteenth, and what do you try to convey to them?

Naomi Greenfield: We did a mini unit on Pride last week, and we did a bunch of read-alouds and a little activity. We read a bunch of books about transgender kids, and I pointed out to them that when I was growing up, these books did not exist. When I was in second grade, there weren’t books about transgender kids. I tried to convey to them that it’s exciting how things change over time. At the same time, I definitely didn’t learn about Juneteenth when I was 8 years old; I learned about Juneteenth when I was in my 40s.

I explained to them that, in the United States, there was slavery for hundreds of years. Because we’re at a Jewish day school, I like to connect the story of slavery and freedom with the Passover story. Basically, the story of Juneteenth is about delayed gratification: Slavery ended, and then it was two years later that enslaved people in Texas found out about it. I said: “Imagine someone said that COVID was ending today, and that you no longer had to distance or mask, but you didn’t find out until you were in fourth grade.” They were immediately like: “That’s so unfair! Why would they do that?” Second graders are very attuned to what’s fair and what’s right, and we talk a lot about social justice in age-appropriate ways.

How much do you think they grasp about racial differences, and is there a proper balance to strike when talking about those differences?

Greenfield: There’s tons of evidence that kids as young as babies understand racial differences and categorize things in their world. There are Black Jews in our community, whether or not they’re in our particular classroom. Part of what we’re doing in school is giving them exposure to things they may or may not have in their lives right now but that they may encounter in the world.

What Juneteenth lessons did you teach?

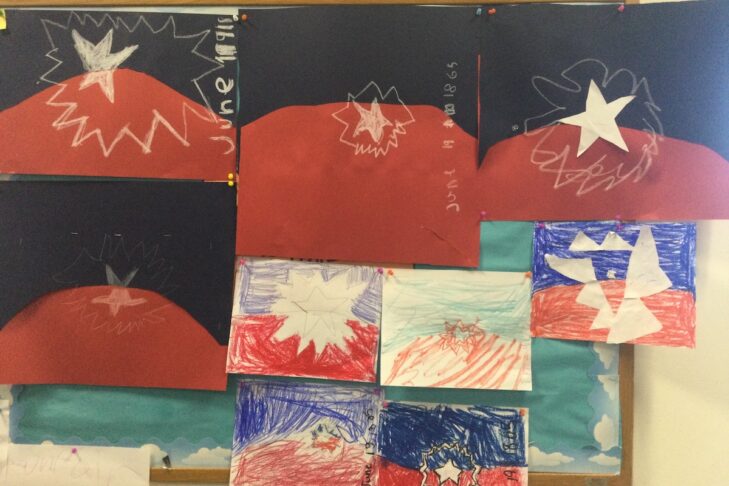

Greenfield: Juneteenth really is a celebration. Obviously, if you dive into the story of Juneteenth, there’s a difficult history in there. But Juneteenth is a celebration of history, culture and freedom. We watched a short video about Juneteenth, and we looked at the Juneteenth flag to talk about symbolism. And we celebrated by having red soda, a traditional drink, and the kids drew their own flags. Then we asked them to write some words with chalk that they thought related to Juneteenth. Some wrote “unfair”; others wrote “freedom” and “justice.” It’s nice for young kids to use lots of sensory input, such as the taste with the soda and holding the chalk.

Nikki Cohen: We talked about the fact that when there was slavery in this country, there was no internet, there were no computers, no phones. Folks in Texas didn’t find out that the Emancipation Proclamation had been passed. In some ways, it’s a happy day; it’s celebrating freedom. But in some ways, it’s a sad day remembering the history of this country. As a Jewish school, I connected it to Passover, celebrating freedom, and talked about how holidays can be happy and sad. You can celebrate the end of something bad but still understand that this doesn’t mean everything is perfectly fair.

What are some of the challenges in talking to kids about this?

Greenfield: They haven’t had a full understanding of history, why there was slavery and the Civil War. They’re getting bits and pieces. It’s when they go into later grades that it gets filled out a little bit. The idea is to introduce them in bite-sized chunks in the earlier grades. You always want to give kids some context, but also they haven’t had that opportunity—but I think that’s OK. I think it’s good for them to get exposure to some of these stories now.

Cohen: If kids ask questions, you can always ask them what they think, because they often have some really thoughtful responses. Or if a kid asks me about a specific piece of information that I don’t know the answer to, I always say: “I don’t know. I’m going to look it up and get back to you.” I think it’s very powerful modeling to say you don’t know the answer. It shows that you’re learning, too.

Sometimes kids are so poignant in their innocence and their honesty that they’re wise beyond their years without meaning to be. Have you gotten any interesting questions from kids about this?

Greenfield: I think the COVID analogy really hit home for them. They had a visceral reaction, and I made it up on the fly.

How do you frame social justice issues more broadly?

Cohen: In first grade, our social studies curriculum is based around symbols of the United States—the flag, the eagle, the seal. We learned about the raised fist on a lot of the Black Lives Matter flags. Images are really powerful for kids, especially images they see in their daily life. It gives them a concrete anchor to focus on.

What do you think is the hardest part for kids to grasp, or the most difficult part of having these discussions, that parents should know?

Cohen: I think first graders are very black and white. Good guys. Bad guys. I don’t want kids to get the impression, well, there was discrimination, but now it’s magically over. So I just try to repeat the same simple message: “Things have gotten a lot better in our country, but that doesn’t mean everything is totally fair.”

Also, not framing people of color as just victims, even though kids are going to have some level of black-and-white thinking no matter what you say, just because of their developmental age. But if you just repeat a few key phrases, like, “Things have improved a lot in our country, but that doesn’t mean everything is totally fair,” or, “There are many people working for justice,” it helps. Or you can just say, “And that’s a sad thing.” It’s OK for you just to state that something was sad. You don’t need to say something to make it better.