Last year, Mimi Lemay posted an open letter to her transgender son, Jacob, born Mia, on Boston.com. The message of love and acceptance went viral. Today, the Melrose first-grader is happily living his life as a boy with two siblings.

“He’s much more comfortable in his own skin after the transition, and he’s living his authentic identity,” she says. At this age, a transition involves dressing or wearing one’s hair like the preferred gender and using gender-appropriate pronouns; hormonal changes, if a child still wants them, come later.

Lemay was raised by her mother in an ultra-Orthodox Yeshivish community, first in Monsey, N.Y., and then in Gateshead, England, where she attended Gateshead Seminary after high school. She returned to the United States at 22.

Her husband, Joe, is Catholic. While she’s no longer ultra-Orthodox, her Jewish background informs her approach to parenting.

Lemay holds many Jewish values close, though, as she’s supported her son’s transition.

“When I was a young girl, I was taught that each Jew was like a limb on a body, and if one suffered, then all suffered. As I left ultra-Orthodoxy and embraced the world at large, I can clearly see how this applies to all of humanity,” she says, especially in her advocacy work in the transgender community.

“The words of the sages, particularly that of Hillel, are very relevant in my advocacy: ‘If I am not for myself, than who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, than what am I, and if not now, when?’ Particularly the last part of that saying resonates with me as we push for legal change, such as the implementation of an anti-discrimination law to protect transgender individuals in places of public accommodation,” she says. “People have told me that if we waited a while, passing the law would be easier, that ‘society is not ready to accept transgender people.’ I would answer, ‘If not now, when?’ When is the right time to treat people with the respect they deserve as human beings, and to afford them basic civil rights?”

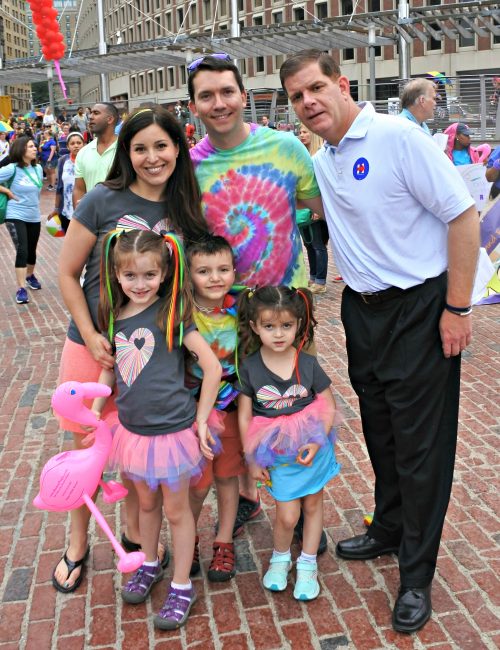

In June, the public accommodations bill passed both the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives, and was signed into law by the governor, she notes. The family was there for both votes.

Today, the Lemays celebrate Jewish and Christian holidays, and Lemay’s mother visits every few months. And God still plays a role in her life, though in ways she didn’t necessarily expect.

“I do believe in God, and I feel that he has been with us this entire journey with Jacob. He has given us a gift that cannot be surpassed: a child who has had the courage and honesty to tell us who he really is and to fight for it. Also, in my struggle to determine my own future earlier in my life, I think I was able to see that Jacob needed us to grant him the right to live as the person he kept insisting he was,” she says. “Shortly after Jacob’s transition, we saw our child go from sullen and angry and withdrawn to joyful and curious and proud. It was literally ‘me-afelah l’orah,’ from darkness to light. Hand in hand with the miracle of Jacob’s ‘rebirth’ came the knowledge and responsibility that there were many others out there who didn’t have the support that Jacob has had. That responsibility has become a primary purpose in our lives. Joe and I, and the kids if appropriate, have spoken with legislators, businesses, schools, the health-care community and others about the need to affirm and support our transgender and gender non-conforming youth.”

This is particularly important because they’re at risk for mental-health issues, substance abuse and suicide. (Suicide attempts for transgender youth under 18 years old are upwards of 50 percent, she says.)

Fortunately, the Lemays’ community has been “wonderful,” she says. “Our local synagogue that we attend sporadically has been very affirming and welcoming, not only to us but to other members of the community who are gender non-conforming. Our schools have been supportive and so have our neighbors and friends.”

Of course, there are thorny issues to tackle—some people ask her how a child as young as Jacob could possibly know that he’s meant to be a boy, and she does worry about what might happen as he gets older.

“While Jacob is treated like every other boy in his elementary school, I have heard from parents in older grades whose children have experienced harassment from peers. I’m working with a group of parents from our community to address this issue with our responsive school administration. There is an opportunity for growth and change here. This is certainly something that a person raised in a Jewish home understands: education is key! After all, we are the ‘people of the book,'” she says. She adds that Keshet has been particularly helpful with advocacy.

That said, the transition has been bittersweet.

“There are moments that I miss my ‘daughter.’ Sometimes it will be a mild twinge when I’m looking at old photographs, and sometimes it wallops me with huge emotional impact, such as when I’m dreaming at night. However, seeing the joy on my son’s face, and knowing that he is relearning to trust himself and others and to navigate his world so beautifully, dispels the sadness. He was always my son; I just didn’t realize that for a few years. I am thankful that I have him, and I will always protect the blessing that he is to us,” she says.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE