Social justice is a big topic for little kids. But Jewish day schools find ways large and small to incorporate it into their curriculum, in keeping with the tradition of tikkun olam (repairing the world). Here’s a snapshot of it in action.

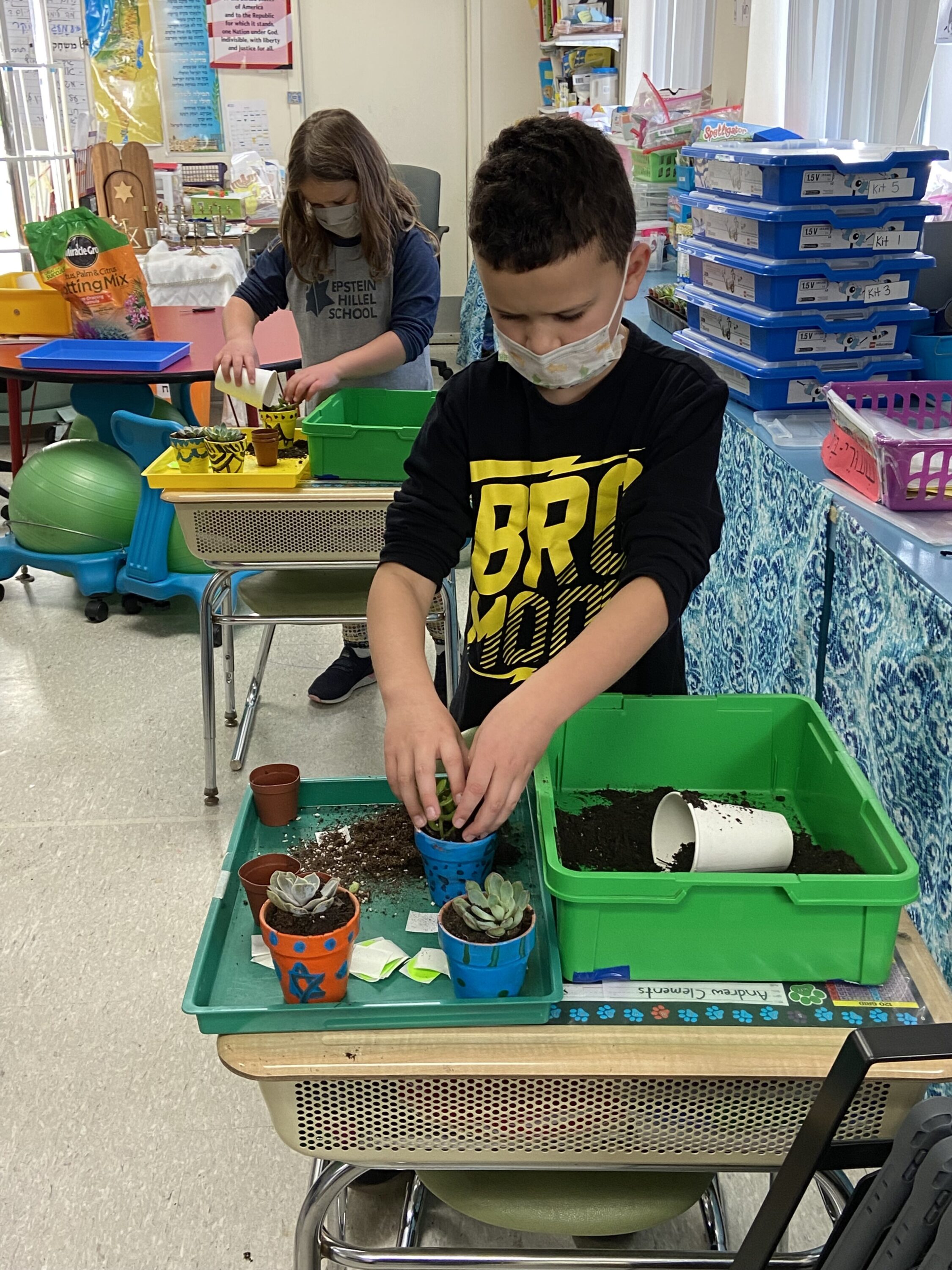

At Epstein Hillel School, Mindee Greenberg, director of enrollment and marketing, says core attributes such as compassion and community inform the curriculum. There’s a day of service right before Thanksgiving, where each grade is matched with a community organization to help, with a presentation from each.

“It’s not just kids, say, making dog biscuits—but really learning about animals in need,” she says. Older kids raked leaves for senior citizens; others made dinner at a homeless shelter or crafted blankets for Mass General’s neonatal intensive care unit.

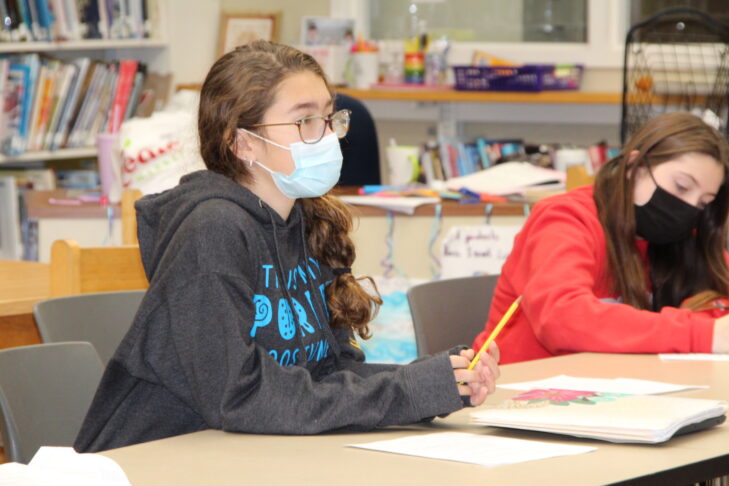

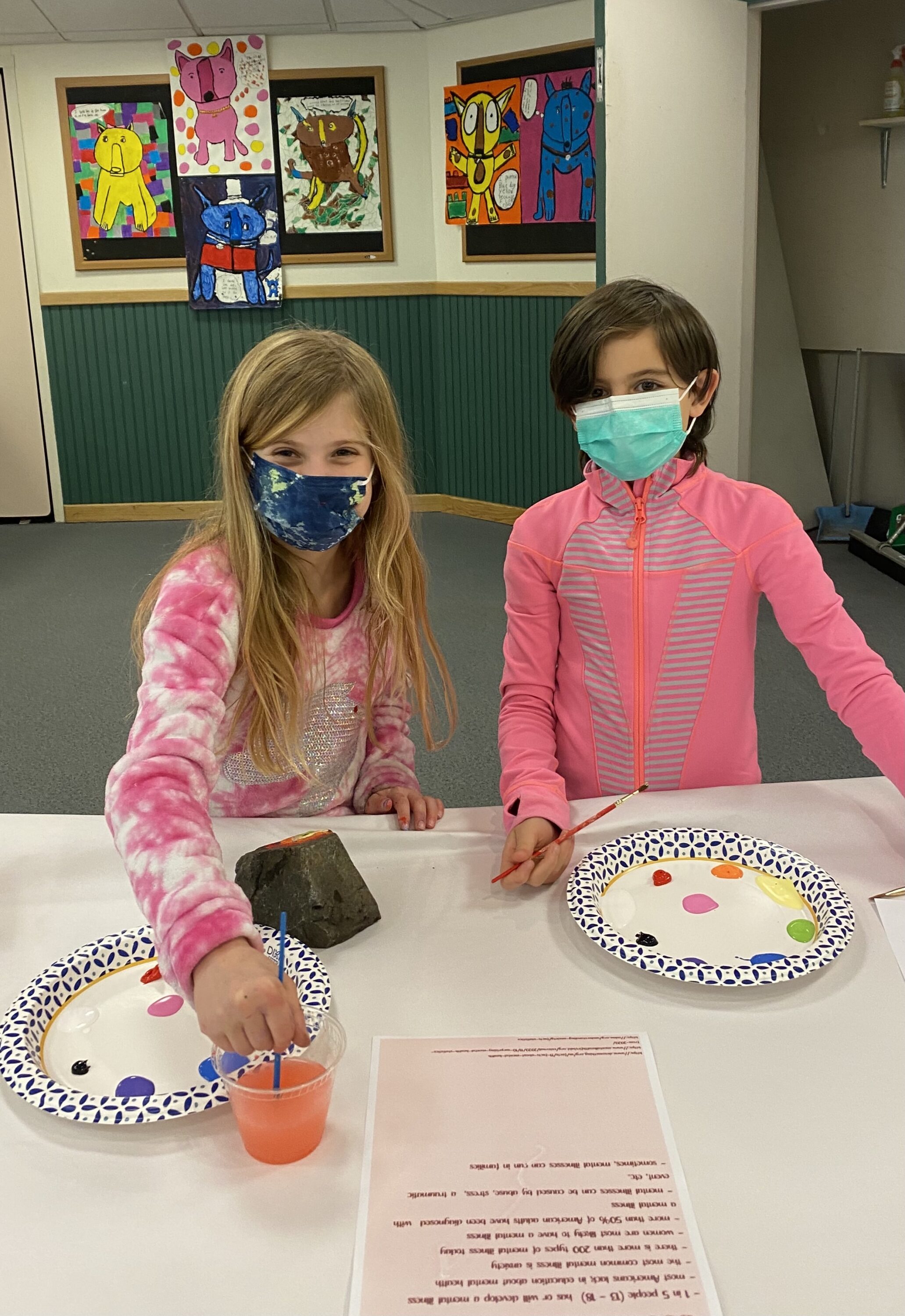

But social justice informs the curriculum in subtler ways, too: English classes that read texts critically to analyze whether characters are treated fairly; in eighth grade, kids use the Facing History & Ourselves curriculum to learn about being an upstander. Before they graduate, kids take on a leadership project about an important topic. Given COVID-19, a recent focus was on youth mental health. They organized an awareness event, with their own budget, to paint kindness rocks, hand out flyers and put bullet points on each table about awareness.

At The Rashi School, “Social justice is essential to who we are,” says Rabbi Sharon Clevenger, dean of Jewish learning. “It’s a call first made in the Torah and has never really stopped being made and heard by and for the Jewish people.”

Rashi aims to challenge kids to find real-world solutions to complex problems, such as climate change and environmental justice, within a broader context.

“We, of course, want students to be thinking about pragmatic steps that they can take composting, recycling, picking up trash—all of those elements that are really important. But we also want them to think about the impacts of climate change on different populations,” she says.

“What we want from a Rashi graduate is not only to be a mensch-y person who does the right thing on a regular basis, but also someone who views the systemic challenges and problems in our world as challenges they can address and whose roots they can tackle and, hopefully, repair, so that the next generation world we’re inheriting is actually a safer, more equitable place.”

To make the concepts less abstract, second graders have a curriculum called “Tzedakah Hero,” highlighting an everyday person doing extraordinary things, such as a second grader who started a food drive at 6 years old while also working on their own grocery budget to understand how expensive food can be. In second through fifth grade, kids learn about equity versus equality.

“We’re really trying to drive home that just because someone has different needs than you do, or needs a different response, doesn’t mean they’re less than or that it speaks to their character; it just speaks to their position,” says social justice assistant Sherman Goldblum.

At JCDS, Boston’s Jewish Community Day School, the Learning for Justice Standards framework (identity, diversity, justice and action) informs its teaching. A cohort of eight to 10 teachers committed to social justice teaching also meet bimonthly and are thought partners for each other. “This year, we’re continuing to bring in the rest of the teacher community by focusing our instructional rounds on incorporating social justice into daily lessons,” says middle school math teacher and social justice coordinator Sarah Langer.

In fourth grade, kids study the Harlem renaissance and the civil rights movement as examples of ways that justice and injustice has shaped American history. The year ends with a change-maker project wherein students note habits and characteristics exhibited by change-makers throughout history and “think about what it means to take a stand for what is right and just,” says fourth grade general studies teacher Danielle Smith.

The school also does lots of programming around refugee support and education. Each Friday at recess, students gather at an “action station,” where they read a story about a refugee kid or family and then complete a project that puts the social justice idea of taking action into motion. Students have made posters to bring to the airport to welcome new refugee families, crafts to sell to raise money for refugee families and blankets for refugee children.

At Schechter Boston, “We really do want our students to feel empowered to change the world, both in thinking about how they’re upstanding members of a Jewish community, a broader American community and thinking about the places where they can be a force for change in the world,” says Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld, director of learning and teaching.

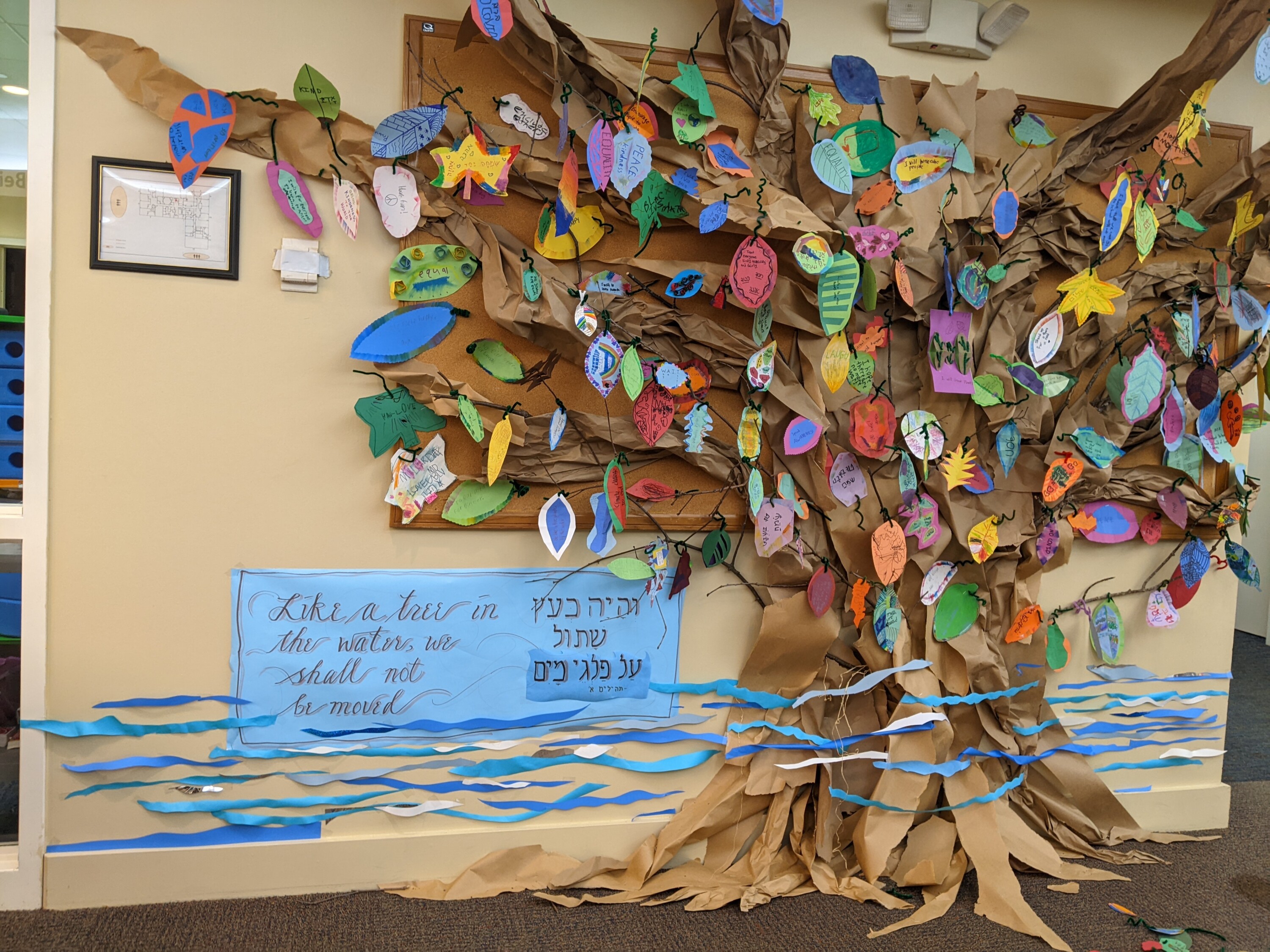

Schechter enrolls kids from kindergarten to eighth grade, so the message is developmentally tailored for the littlest students: What good deeds do you do for friends and family? Kindergartners just completed a “mitzvah tree,” where they wrote their generous acts on trees. Second graders interview immigrants to learn about the different ways people arrive in America. Sixth graders undertake a unit on poverty and hunger in the Boston area, where they meet people struggling with food insecurity. For hands-on work, they conducted a coat drive to support refugees.

Hassenfeld says Schechter tries to put the focus on local community whenever possible to humanize the issues.

“It’s really trying to send the message that we’re all in this together; everyone is a teacher and everyone is a learner,” he says. “One of the reasons I love working in a Jewish school is that there are values we’re trying to inculcate in students—as important a part of our work as teaching math.”