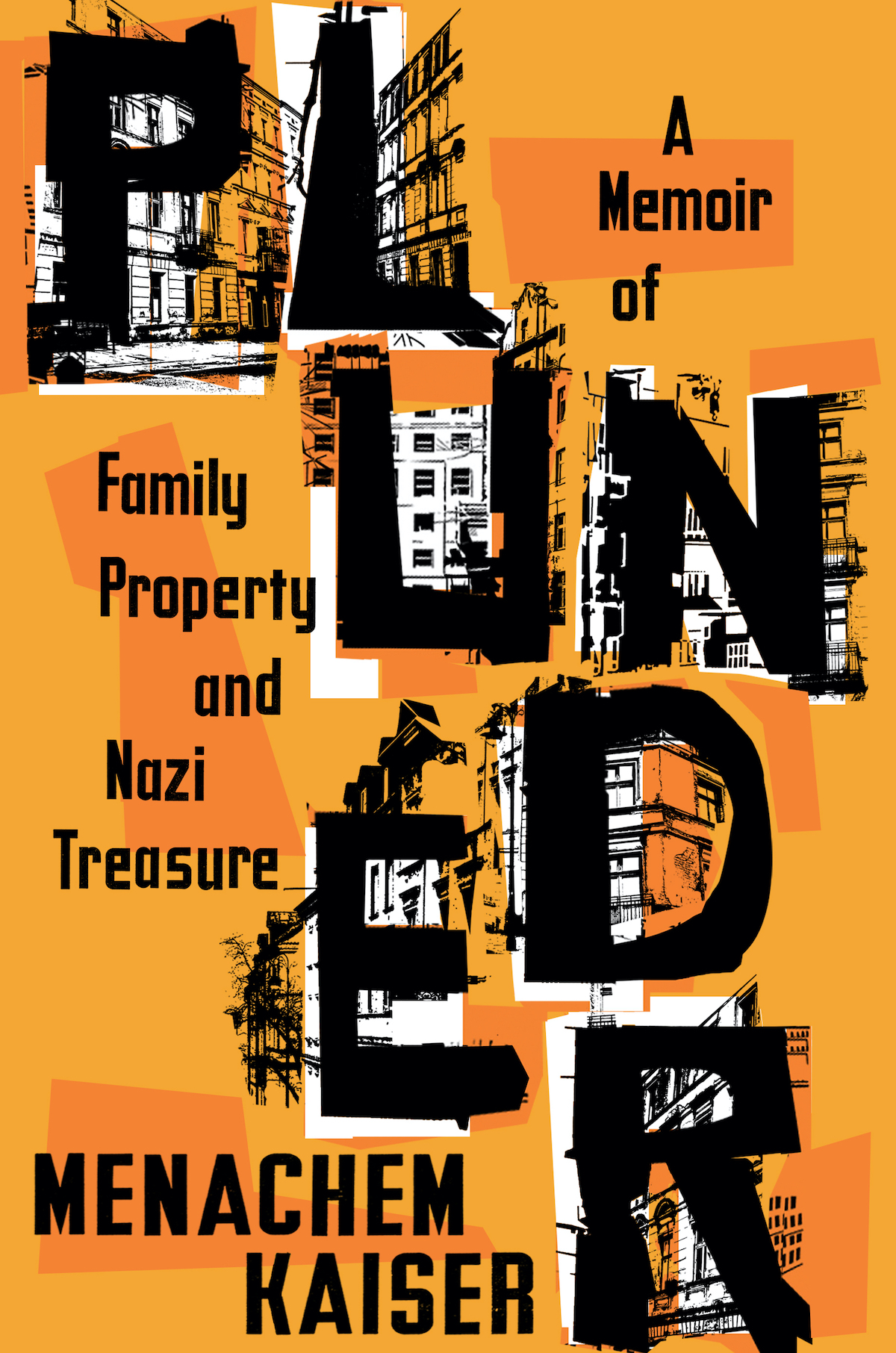

The title of Menachem Kaiser’s recently published memoir, “Plunder,” almost begs for an exclamation point. The subtitle, more explanatory yet no less intriguing, indicates that the reader has encountered “A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure.”

The Toronto-born Kaiser lives and writes in Brooklyn. He has a master’s degree in fiction writing and considers himself, first and foremost, a novelist. A novel-in-progress has been sitting in his desk drawer for a couple of years. But this story of reclamation, an outstanding addition to the growing literature of third-generation (or “3G”) survivors of the Holocaust, was the one he first had to tell publicly. It’s the tale of how he set out to reclaim a building owned by his paternal Holocaust survivor grandfather before the war in Sosnowiec, Poland.

Kaiser’s efforts to reclaim his family’s inheritance sometimes devolve into a comedy of errors. At other moments, his frustrations with Polish courts are tangled up in the current government’s far-right politics. Throughout, Kaiser is aware there are limits to his project even as he is cold-calling on the residents at Małachowskiego 12—the address he has on paperwork his grandfather filed decades ago to reclaim the building. Kaiser’s grandfather died eight years before he was born, making the grandson question if he is even a 3G survivor and if he is writing a bona fide Holocaust memoir.

“I do not trust the genre I am writing in,” Kaiser writes, “that of the grandchild trekking back to the alte heim [ancestral home] on his fraught memory-mission—it’s too certain, too sure-footed, meaning is too quickly and too definitively established; there is no acknowledgment of the abyss, the void, the unknowable space between your story and your grandparents’ story. (I admit I’m also jealous—all the other grandchild authors seem to be able to so easily access the memory and meaning of the memory of their grandparents.)”

It turns out that Kaiser’s legacy is not only bound up in reclaiming Małachowskiego 12. There was the bureaucratic absurdity—although Kaiser is too diplomatic to call it that—of navigating the Polish legal system. He hires an octogenarian lawyer whom he nicknames “The Killer.” In addition to her presumed legal prowess, she wears a loud pink velour tracksuit underneath her sober black judicial robes. Before Kaiser can lay claim to his grandfather’s property, The Killer must jump through Kafkaesque hoops to prove that his ancestors—relatives who would range in age from 130-140 if they were still alive—died in the Holocaust. His legal team of two—The Killer and her daughter, who translates for her mother—encounters a number of obstacles. At one point, the details of the case become so convoluted that Kaiser hires a second lawyer to explain The Killer’s strategy.

Kaiser’s legal woes take a backseat when he hears about a group of treasure hunters obsessed with seven extensive complexes carved into the Owl Mountains in Silesia. The site is called Project Riese—“riese” means “giant” in German—and it is narrative gold for Kaiser. He sits around campfires listening to conspiracy theories drenched in vodka. He’s a good listener and paces his drinking to take in the larger-than-life details about anti-gravity and time machines and Nazi flying saucers.

The “plunder” of the book’s title comes into sharp relief when he hears about a legendary Nazi gold train filled with looted Jewish treasures possibly stuck on underground tracks. Despite various searches over the years, the train has never materialized. In bringing up the train, Kaiser makes it clear that everyone, including him, is mining the past in his own way.

Kaiser comes to understand that most of the hunters are not looking for objects but answers. “One guy I met spent years going through archives and interviewing locals who led him to the site of a concentration camp that had been wiped off the map,” he recalls. ”I learned about an ongoing attempt to locate a field with a mass grave where thousands of Jews were shot. Other hunters have found a Nazi medical laboratory.”

Things are even more surreal when various hunters ask Kaiser if he is related to Abraham Kajser. Kajser wrote a memoir called “Behind the Wires of Death” that has morphed into a guide-cum-bible for these explorers. A Jew whom the Nazis used as slave labor, Kajser was instrumental in building the underground complex when he was imprisoned in a series of brutal sub-camps connected to the Gross-Rosen labor camp. He laid out the construction of the tunnels in detail. His memoir has a Talmudic-like resonance for these men (and they are almost all men) who dress in camouflage and drive Jeeps and Land Rovers. Kajser’s book, which was only available in Polish until Kaiser commissioned a private English translation, does a brisk business in Project Riese’s gift shop.

Kajser’s story of survival was complicated, and at the end of the war, having lost his wife and young son, he immigrated to Israel. His memoir was translated into Hebrew in the early 1950s but went out of print in a couple of years. Kaiser, a prodigious researcher, discovers that Kajser was his grandfather’s first cousin. However, as Kaiser points out, a first cousin is a close relation “when a family is wiped out. I came in with the understanding that my grandfather had no surviving family members save one on his mother’s side who lives in Israel. In discovering Abraham, the family went from extinct to non-extinct. It was a big shift in my family’s conception of its own history.”

Back in Sosnowiec, Kaiser’s court case remains in limbo. A year becomes two and then becomes five. The Killer hasn’t succeeded in declaring Kaiser’s relatives legally dead. But this fascinating, wholly original book is not about restitution. It’s about reclaiming history. Kajser recorded his diary entries on empty concrete bags that he buried in latrines. He later retrieved them, and they became the basis of his memoir. Says Kaiser, “If you look in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum encyclopedia of ghettos and camps, Abraham Kajser is the primary source for several camps.” In light of that critical fact, Kaiser has notably succeeded in claiming a precious piece of Holocaust history.