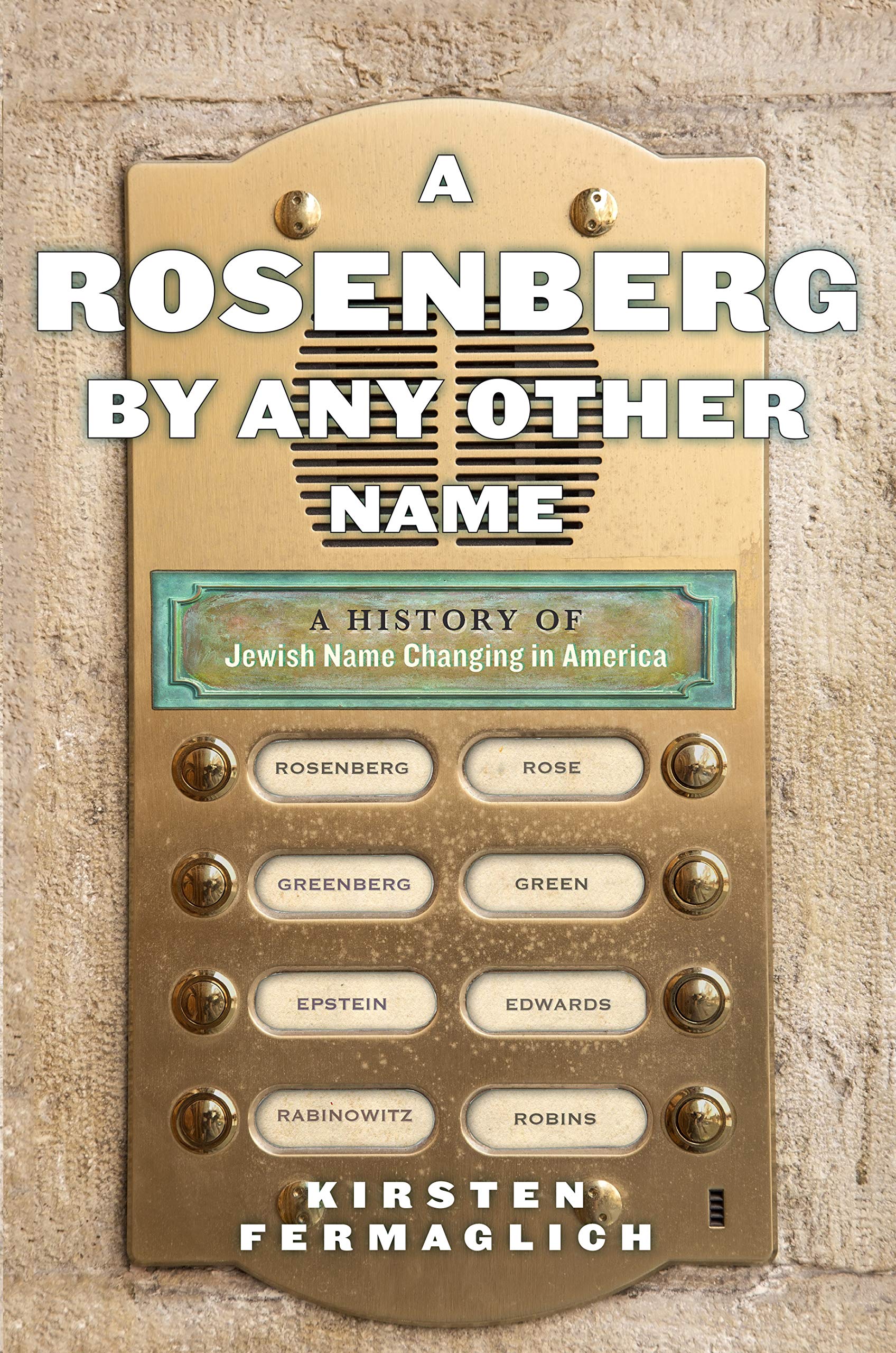

Historian Kirsten Fermaglich likes to joke that having an unusual last name led to her interest in surnames. It also led her to look at early- to mid-20th century American Jewish history through the lens of Jewish name changing. Fermaglich’s engaging book, “A Rosenberg by Any Other Name: A History of Jewish Name Changing in America,” surveys the myriad reasons—cultural, psychological and sociological—that Jews changed their patently Jewish names.

Fermaglich considers the obvious reasons for anglicizing a Jewish surname—upward mobility and antisemitism. Her research goes deeper into the consequences of losing part of the identity and personal history connected to one’s Jewish name. Despite those consequences, Jews disproportionately petitioned to change their names in New York City, including entire Jewish families who changed their names together. Yet Fermaglich discovered that the majority of Jews who changed their names remained connected to religious and cultural Jewish life.

Fermaglich is an associate professor of history and Jewish studies at Michigan State University. “A Rosenberg by Any Other Name” won the 2019 Saul Viener Book Prize, given by the American Jewish Historical Society. Fermaglich will be speaking about her award-winning book at the Vilna Shul on Thursday, Feb. 27.

She recently spoke to JewishBoston about her unique research.

What are some of the things Jewish name changing showed us about 20th-century Jews?

One of the key things Jewish name changing showed us was the reach antisemitism had in people’s lives in the first half of the 20th century. Until recently, people knew there was antisemitism in the form of restrictions in schools or finding jobs in certain areas. But it’s been frequently downplayed. Antisemitism affected people’s lives to the point that they felt the need to change their personal identities and that of their families. In doing so, they faced criticism, humiliation and skepticism from friends and family members. Antisemitism had a more powerful impact on people’s daily lives than historians initially realized. There’s been a shift, and historians are reconsidering that angle.

What does name changing say about Jewish success?

It says it was a lot harder for Jews to achieve success than people realized. Not only was it difficult, but there was also a cost to it. People lost these names and were forced to change their identities. As I conducted my research in files that were stored in the backroom of the New York Civil Court, I read pages and pages of names that had been changed. There were pages of Cohens and Goldbergs and Greensteins. These names were being erased. It’s important to understand that there was a cost to Jewish success. We have to understand what people gave up to succeed.

Another finding of yours was the relatively high number of Jewish women who changed their names.

I discovered that a third of the petitions to change a name in the mid-20th century came from women. Although 20% of the Jewish female petitioners were children doing it with their family, single Jewish women were entering the workforce in larger numbers than many other white ethnic groups. There were a lot of stereotypes about Jewish women workers and why they were inappropriate for the workforce. Name changing was one way to avoid being targeted.

Your research method was relatively unique. Tell us about it.

It was unique in that the materials I used were not in archives. It was a different process. When I started researching my book, I stood in line with people changing their names in real time to look through court files. I improvised and used the boxes of files as a desk. Most importantly, the experience of doing my research in this unusual way made me more sympathetic to people changing their names.

Standing in line I met transgender people, women of color and poor people. They faced a lot of bureaucracy to change their names. Unlike Jews changing their names in the mid-20th century, these people were not interested in upward mobility. Many of them were fixing bureaucratic problems on birth certificates so they could get their Social Security payments, Medicare or Medicaid. The name on their birth certificate didn’t match their names on other documents.

Why is World War II a crucial moment in the history of name changing?

One of the most interesting things was seeing the importance of bureaucracy during World War II. Men were being drafted into the army, defense plants were hiring and the government needed to keep track of people. People were required to have a birth certificate that matched their names on other forms. People had changed their names unofficially, and now there was an explosion of official name changing.

Antisemitism was also a live fact on the home front. There was antisemitic graffiti in public places like subway platforms, and there was a rise in hate groups. Jewish soldiers were humiliated with discriminatory beliefs such as Jews don’t fight, or Jews are cowards. With the impact of antisemitism, the entry of Jews into the military, the desire to help the war effort as well as the growth of government bureaucracy, Jews paid more attention to their names. They were subtly encouraged to change their names. The highest number in the 20th century of name change petitions happened in 1946. Forty percent of those petitioners were veterans and their wives.

What was one of the more surprising discoveries you made in researching the book?

I was surprised that name changing figured in civil rights activism and legislation. New York was the first state to pass an active civil rights bill with a commission similar to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, where complaints could be filed. That legislation noted that application forms could not be discriminatory. The committee that administered this legislation began gathering application forms from employers and monitored them to see if they were discriminatory. There were questions such as: Have you ever changed your name? Has a parent changed your name? What is your mother’s maiden name? These questions were examples of discrimination.

Jews who were active in the civil rights movement in concert with African Americans knew what it was like to be discriminated against. Name changing enables us to focus on this earlier element of civil rights activism—activism that showed specific and concrete ways Jews faced discrimination. That discrimination shaped the way Jews saw civil rights, name changing and racism.

This interview has been edited and condensed.