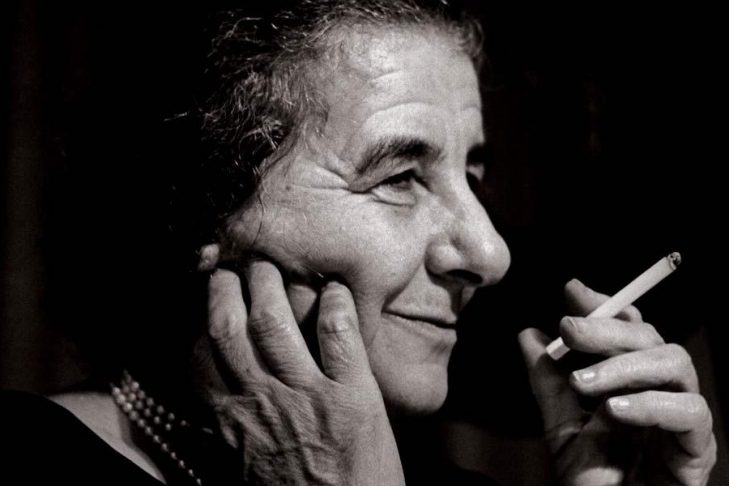

The anniversary of Golda Meir’s 120th birthday was May 3, 2018. Golda, as she insisted on being called throughout her life, was Israel’s fourth prime minister and the only woman thus far to hold that office. She was also very much an icon—feminist and otherwise—of the 20th century. Born in Kiev in 1898, Golda immigrated with her family to Milwaukee when she was 8 years old. She was a Zionist from an early age, and eventually moved to Israel at the age of 23.

Golda married her American sweetheart, Morris Meyerson, and settled on a kibbutz in what was then northern Palestine. Those are the bare-bones facts with which Francine Klagsbrun recently introduced her biography of Golda at Brandeis University’s Schusterman Center for Israel Studies. Klagsbrun gave an overview of her book and was then joined in conversation by Judith Rosenbaum, executive director of the Jewish Women’s Archive.

Weighing in at over 800 pages, “Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel” is a substantial book. It’s also an important book that recently won this year’s Jewish Book of the Year, an Everett Family Foundation award administered by the Jewish Book Council. The book, which took 10 years to write, is meticulously researched. Its size may initially be intimidating, but Klagsbrun’s narrative is engrossing. She portrays Golda as a woman of myriad contradictions. “She was very much an insider in a man’s world,” noted Klagsbrun, “something that feels in opposition to her grandmotherly image. But she was also an outsider—a woman in what was so completely a man’s world.” To that observation, Rosenbaum responded that Golda “was able to harness things that could have marginalized her and made them into sources of strength. Her American-ness made her an outsider yet bolstered the U.S.-Israel relationship. She made use of her gender by putting herself out there in a different kind of way.”

During those early years in Israel, Golda’s leadership skills were recognized, and she quickly climbed through the ranks of the Histradut—Israel’s Labor Union—and eventually the Labor Party. She left the kibbutz and settled first in Tel Aviv, and then Jerusalem. She was permanently separated from her husband (they never formally divorced) and was a single working mother to her two children. “She always worked and had lovers,” said Klagsbrun. “And yet she totally rejected the women’s movement of the 1970s.”

For Rosenbaum, Golda’s rejection of feminism was not surprising. “It’s familiar to encounter women who break barriers but distance themselves from women’s movements,” she said. However, Golda’s antipathy toward the women’s movement did not translate into anti-feminist policies for women in Israel. She supported important legislation that not only protected working women, but also instituted paid maternity leave. “Golda was a socialist and believed that all of society should be equal for men and women,” said Rosenbaum. “There was no need for a separate movement.” By the 1930s Golda was leading a women’s organization in Israel known as Naamat, or “Pioneer Women” in the United States. (She later claimed never to have been associated with any women’s groups in Israel.)

In the 1930s she traveled between the United States and Palestine often and was sent to the Evian Conference in France that aimed to solve the ongoing Jewish refugee problem. The “Final Solution” had not yet been implemented, but droves of Jews had been thrown out of their countries. Golda watched as 31 of the 32 participating nations refused to allow these Jews to take refuge in their countries. “That was a turning point for Golda,” noted Klagsbrun. “She said that she hoped she would live long enough when the world would not reject her people. ‘We will always need friends in the world, but we can only rely on ourselves,’ Golda said.”

In 1947 the United Nations partitioned Palestine, and Israel’s first president, David Ben-Gurion, knew that as soon as the State of Israel was declared it would have to be defended. He sent Golda to the United States to raise funds for arms for the nascent Jewish state. In Chicago she made an indelible impression when she told her audience that the Jews in America could not decide if their fellow Jews in Israel would fight; what they could decide was who would be the victor in that fight. Would Jews or Arabs win? Golda subsequently traveled around the United States and raised an unprecedented $50 million for Israel.

By 1969, Golda, who had been labor minister and foreign minister, became prime minister. At the time, she was one of three women in the world to head a government and the only woman who did not follow a father or husband into office. She took office at a time when there was still a sense of hubris in Israel after winning the Six-Day War so spectacularly. In 1973, the Yom Kippur War upended Israel’s sense of security in the region, and Golda was blamed for not anticipating the surprise attack. She resigned four months later.

In her book, Klagsbrun points out that Golda took office when Palestinian nationalism exploded into terrorism. “She didn’t understand Palestinian nationalism,” said Klagsbrun, “nor did she understand Mizrahi Jews. Nevertheless, she was a strong leader who blamed herself for listening to her generals instead of her intuition when it came to the Yom Kippur War.”

Rosenbaum highlighted the cultural gaps Golda experienced with Jews of other backgrounds. “As a founder of Israel, there was a missed opportunity with Mizrahi Jews. She was such a champion of their immigration, but could not understand their identity,” Rosenbaum observed.

Golda died in 1978 after losing her decades-long battle with lymphoma. Before she died, she met Anwar Sadat on his historic trip to Jerusalem in 1977. As Rosenbaum so insightfully noted: “Golda had the founders’ view of Israel flavored with the Diaspora Jews’ commitment to the Jewish people. ‘Lioness’ opens up to encounter Golda as more than just a symbol, but as a complicated, fascinating person. We learn from her successes rather than her mistakes.”