“Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” opens Boston Jewish Film’s Summer Cinematheque, followed by a Ukrainian Holocaust story, a personal exploration of intermarriage and Jewish identity and an encore performance of a film about Israeli and Palestinian women enrolled in a film course.

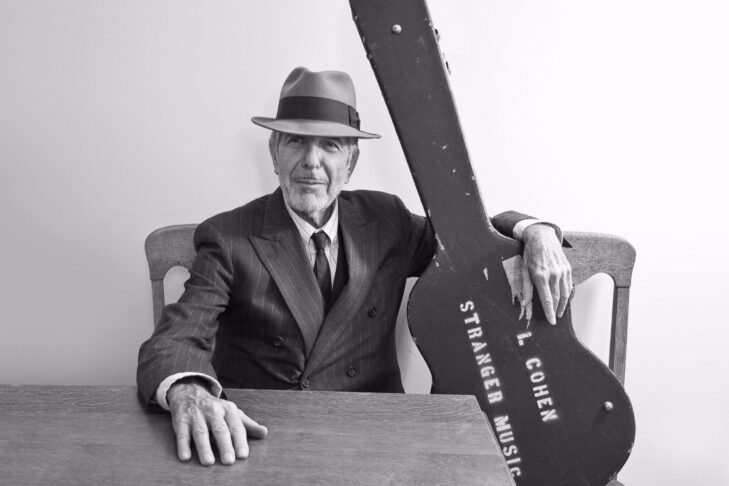

“Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” (in-person screening on July 13 at 7 p.m. at West Newton Cinema)

Despite its clunky title, “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” makes sense of the long, winding history of Leonard Cohen’s iconic song “Hallelujah.” Now legendary, the song had a long gestation period and was a work in progress from the 1970s through the early 2000s, a development visualized in the film with the myriad notebooks Cohen filled writing stanza after stanza. Those notebooks convey an understand of how the song became a poetic hymn with a soul.

Over the years, “Hallelujah” reflected Cohen’s strengths as a poet and songwriter. The song first appeared on his 1984 album “Various Positions.” However, it was not an auspicious debut for what would become a 21st-century spiritual anthem. Executives at Columbia Records hated “Various Positions” and refused to release it in the United States. Nevertheless, one critic described Cohen’s voice as a “low-pitched drone, a stranger to any kind of vibrato, direct and becalmed; it seemed to scrape the bottom of the ocean and get to the heart of things.”

The song fell into obscurity, but like its author, “Hallelujah” has had many lives. In the 1990s, Welsh singer John Cale revived it, and since then, people such as the late indie songwriter Jeff Buckley, Rufus Wainwright, Bono and k.d. lang have covered it. When Wainwright recorded the song for the “Shrek” soundtrack, the song became a huge hit.

The documentary takes us through the stages of Cohen’s life—he was born in Montreal to a prosperous Jewish family. We meet him as a handsome young troubadour, in middle age as a master of lyricism and a resident in a zen monastery for eight years. Then, as an older man, he lost his money to a crooked manager and managed to launch a spectacular second act. The film shows that everything Cohen has done for 50 years has been with “Hallelujah” as his North Star.

“Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” makes it clear that Judaism, the cadences of Jewish liturgy, which Cohen said originated in “the charged speech I heard in the synagogue, using language in a sacramental way,” propelled him. One of his last concerts took place in Israel, where he called for Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation and ended the show by giving the priestly benediction in Hebrew. He was 75 years old.

Cohen died in 2016 at the age of 82. And the film ends with a knowing observation from him: “You look around and see a world that is impenetrable and can’t be made sensible. You either raise your fist, or you say hallelujah. I try to do both.”

“Carol of the Bells” (in-person screening on July 20 at 7 p.m. at West Newton Cinema)

One of the most popular Christmas songs, “Carol of the Bells” harkens back to a popular Ukrainian folk song called “Shchedryk,” imbuing the season with the spirit of peace and unity for all humankind. The original song tells the story of a swallow flying inside a house to signal that the family will have a prosperous year. The song is also a leitmotif threaded through the film of the same name. Made on location in Ukraine, the film depicts the fate of three families—Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish—sharing a large house on the border between Poland and Ukraine. The families grow friendly, sharing meals and musical evenings that Sophia, a piano teacher, arranges.

It is 1938, and a Nazi invasion of Poland and what is now parts of Ukraine is imminent. The Jewish family has been ordered to report to Nazi headquarters, but the parents have the foresight to leave their young daughters in Sophia’s care. That decision saves the girls’ lives. Sophia hides the girls and takes care of the Polish girl after her mother’s arrest. The film gathers momentum as an affecting depiction of selflessness and love. Although the events are fictional, it is a heartrending portrait of a righteous gentile.

After the war, the Soviet occupation is brutal in its own way. The Nazis executed Sophia’s husband as a spy, and the Soviets detained her as a political prisoner. The last we see of her is in a penal colony in Siberia. The children in her care are remanded to an orphanage in the Soviet Union, where Sophia’s daughter is sent to juvenile detention for singing “Shchedryk” at a school concert. The young girl’s bold and patriotic move makes the message of love and personhood in “Shchedryk” ever more resonant as the people of Ukraine fight today to live with dignity and peace.

“Cinema Sabaya” (screening online from Aug. 3-9)

In an encore performance from Boston Jewish Film’s March 2022 Israeli Film Festival, “Cinema Sabaya” centers on a fictional group of eight municipal workers—Israeli Arabs and Jews—in the working-class mixed town of Hadera, between Tel Aviv and Haifa. The women are enrolled in a filmmaking workshop led by Rona, a young Israeli director. The film’s director, Orit Fouks Rotem, led similar workshops in the mixed Jewish Arab northern city of Acre and at Givat Haviva, an Israeli organization promoting reconciliation between Jews and Arabs.

An affecting piece of symbolism begins the film as these Arab and Jewish women note that the word “sabaya” has very different meanings. In the Arabic pronunciation, the word means “prisoner of war.” In Hebrew, it means a group of young women. These women will come to experience both definitions as they explore their lives through the short, impromptu films they shoot.

The film’s action unfolds in a classroom, where the participants’ films are screened during their weekly group meeting. The revealing snippets show both the limits and infiniteness of art. What’s shown and isn’t shown is revelatory. A young Arab woman, the mother of six young rambunctious boys, wears a hijab and wants to obtain her driver’s license despite her husband’s disapproval. She films the chaos of her family life in a cramped apartment, and the audience witnesses her emotional and physical challenges. An Israeli mother worries about sexualizing her 12-year-old daughter if she allows her to shave her legs. An Israeli Arab lawyer dreams of singing on stage.

Soon enough, these women discover the power of experiencing their stories on a large screen. In the process, this film shows that these women have been given the opportunity to go to places with their art that previously only existed in their dreams.

“American Birthright” (screening online from Aug. 10-16)

Filmmaker Becky Tahel’s intimate documentary investigates the question of whether it is important for Jews to “marry Jewish.” Finding an answer became urgent for Tahel when her younger sister, Gal, a medical student, married a man who is not Jewish. Tahel and her sister were born in Haifa and came to the United States with their Israeli parents at 6 and 3, respectively. Their parents raised them as cultural rather than religious Jews. Yet her sister’s nuptials created a deep division within the family, especially for Tahel and her grandmother, a Holocaust survivor.

The subject of “American Birthright” is timely for American Jews, more than half of whom have married a non-Jewish spouse, according to a Pew Research Center report. Interfaith marriages and interfaith families are now a fact of American Jewish life. “American Birthright” takes these interfaith issues a step further and evolves into the more complex question of why be Jewish?

Much of the documentary follows Tahel as she checks off items on her “to-Jew” list, including studying Torah at a liberal Orthodox yeshiva in Jerusalem, taking on more traditional Jewish observance, dressing modestly, observing Shabbat and praying regularly. While exploring her newfound Judaism in Jerusalem, Tahel keeps the cameras rolling as she returns to Haifa, her childhood home. In one of the film’s most poignant moments, Tahel is moved to tears at her grandparents’ graves in Haifa. Both were devout Jews, and in that scene, Tahel is acknowledging that her connection to them is more profound than she realized.

In the end, Tahel produced a film of her life replete with a happy ending. These days she describes herself as “Torah observant” and is married to a religious filmmaker and musician. The couple is expecting their second child. Tahel attributes the changes in her life to making a documentary that unexpectedly exerted a “mystical magical power” over her.