On an afternoon in 1987, 14-year-old Christian Picciolini was hanging out in his working-class Chicago-area neighborhood smoking a joint when an unfamiliar man abruptly approached him, yanking the joint from his hand. “Don’t you know that’s what the Jews and Commies want you to do to keep you docile!” That fateful afternoon marked Christian’s initiation to the dark world of the white power movement. Christian soon became a member Chicago Area Skinheads (CASH), one of the country’s oldest neo-Nazi skinhead gangs. “What they told me was, ‘Come with us. We’ll take care of you. You’ll have friends. We’ll have your back.’”

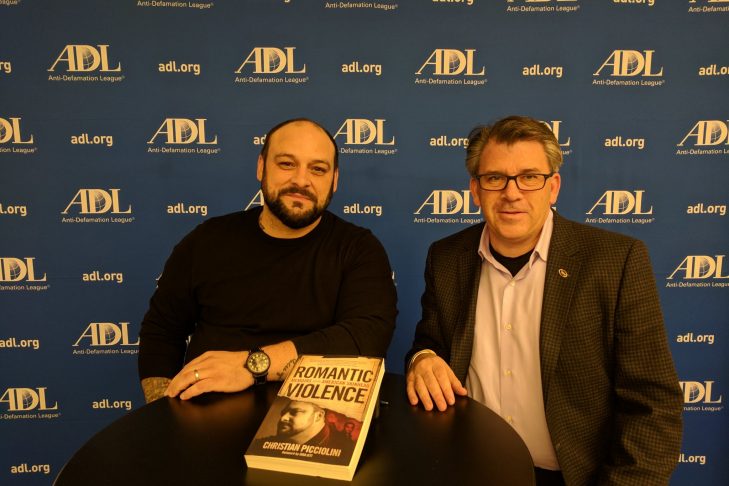

In 2009, Christian co-founded the non-profit organization Life After Hate, whose primary focus is to rehabilitate individuals who’ve become involved in the white power movement. He is now working to build the world’s first global network of extremism preventionists, who are helping people disengage from hate movements and other violent ideologies around the globe. His own journey to the reformed man he is now was a long, hard one. With a warm smile and a humble demeanor, it’s hard to imagine Christian as the former face of violent neo-Nazi gang as he had been nearly 30 years ago. He has just one tattoo left over from his neo-Nazi past—Nordic runes that wrap around his arm, which is a popular symbol among skinhead members. He has opted to forever keep this particular tattoo, while he has removed the more recognizable ones. Ten years ago, he was walking down the street when a young man he didn’t know stopped him, “Hey man, nice tattoo—white power!” Years out of the white power scene, Christian talked to him for a full hour about why he was involved in the movement and the truth behind it. “We shook hands and parted ways. I don’t know if he ever got out or what became of him. But I’ve kept the tattoo all these years as an ice-breaker.”

The son of Italian immigrants, Christian’s early childhood was marked by isolation—at home and at school. His parents worked long hours to support the family, leaving him home alone often and resentful because of it, and he suffered countless bullying from peers at school. “I kept hitting a wall when trying to find acceptance.” He describes himself as the ideal target for the gang member who approached him that fateful day—vulnerable, isolated, desperately seeking purpose and acceptance and easy to manipulate. The skinhead gang represented a promise of acceptance and brotherhood, and most notably, power, where he sorely lacked them elsewhere. The ideological tenants of white supremacy provided Christian with a plausible-enough narrative of why his life was coming up short. Incidentally, two weeks after the skinhead approached him in the alley way, three black kids stole his bike. That was the last straw he needed to surrender himself to the white power cause. But the gang’s appeal to Christian went much deeper than belief. “Ideology and dogma are not what radicalize people. What drew me in was a broken search for identify, community and purpose. It went from white pride to we must eliminate everyone who’s not like us. And white supremacists would eliminate everybody, including themselves. They hate themselves that much.” Christian quickly rose through to the leadership ranks after the man who had originally recruited him went to prison for assaulting another member. He soon began representing the white power movement on major talk shows and news outlets like CNN.

Despite his prominence in the movement, Christian internally harbored many doubts and confusion over the ideology that he was supposed to be fighting for. After all, his involvement baffled and horrified his parents, who had been victims of racism themselves as Italian immigrants. The slow beginning of the end began when he opened a white power music record store in 1994. Despite the store’s known focus on racist music, people of all backgrounds still frequented his shop for the mainstream music that he also kept in stock. Christian found himself befriending many of these non-white patrons and was struck by their lack of judgement and willingness to befriend him. “These were strangers who knew who I was. What saved me was the compassion I received from people that I didn’t give it to and did not deserve it from. They saw something in me that I didn’t see. I was able to understand that we had more similarities than differences. The demonization that had been inside my head was destroyed because it no longer fit.” On top of that, Christian’s first child was born in 1994, shifting his formerly hostile outlook in life. “I remembered what it was like to love something.” Now that he was responsible for a family, Christian also found it increasingly difficult to ignore the sleazy inner-workings of the neo-Nazi world. He was adamant for his wife to not become involved in the movement because he knew it hid a culture of extreme misogyny—where women were outwardly propped up as “Aryan goddesses” and used as propaganda mouthpieces—but were victims of vicious treatment, including countless assaults and rapes, behind the scenes.

Christian officially renounced his ties to the white power movement in 1996 but the path to redemption was still a difficult one. Having ceased to stock white power music, he was forced to close his business since it had lost its primary revenue source. His wife left him soon after, and Christian, alone without his family and the community he had known since his teenage years, fell into a deep depression for five years. Re-joining the movement would have been easy, but Christian was able to pull through this depression by slowly coming to terms with his past and learning to share his story, despite fear that others would judge him as harshly as he had judged in his past. “It would have been very easy and comfortable to go back while I was going through this depression. It’s like detoxing from drugs and then just going back to using. If I hadn’t had the support of people, strangers and friends, who would not let me go back, I could have easily gone back.”

His past affiliation continues to haunt him especially now as the visible presence of white supremacy in today’s political climate has increased. “What we’re seeing now is the metastasis of the cancer that it was.” Enrollment among white supremacy is up, and he recognizes much of today’s political rhetoric as not so different from the rhetoric he and his fellow gang members used 30 years ago like building a wall and expelling immigrants. Christian also expressed frustration towards those who downplay the threat posed by white supremacy groups. “We don’t call white extremism terrorism. What most people don’t realize is that since 9/11, more Americans on U.S. soil have been killed by white supremacists than any foreign or domestic terrorists combined. And we still don’t call it terrorism.” Christian emphasizes that politicians, media and the public need to start calling white supremacy terrorism or else it will not get the attention and resources required to combat it. “Today is a watershed moment for this country. They’re a small minority but still a large number and they’re reshaping the vision of what America should be as long as they continue to grow.” Christian remains hopeful, though, especially reflecting back on the people who supported him throughout his hard-fought journey out of white supremacy. “I have hope because there are more good people in this country than bad.”

Christian likens participation in extremist groups like the neo-Nazis and ISIS as similar to a drug addiction—something that people turn to anesthetize some sort of trauma or shame, whether it’s lack of money, lack of education, abuse, extreme neglect or insulated privilege. “Toxic shame drives so much violence, so much hatred.” His current work focuses on identifying these traumas in individuals and working to heal them whether it’s a poor education, low confidence or lack of employment. His other strategy is to introduce his clients to people they think they hate. He’s introduced people who claim to hate Muslims to Imams and Holocaust deniers to Holocaust survivors and has seen the impact these meetings have had firsthand. Christian warns that getting into ideological debates with neo-Nazis is all but useless. “Don’t debate a neo-Nazi because you’ll never win. Their ideology is not based in any logic. Instead, I focus on what went wrong in their lives that made them vulnerable to the manipulative tactics of neo-Nazis and work to heal those potholes. Get them a life coach, mental health treatment, job coaching whatever it is.” If arguing with a neo-Nazi is useless, physical violence against them is even more counter-productive. Christian warns that the physically aggressive tactics employed by Antifa and other anti-fascist groups play right into the white power movement’s hands because it fuels their “white genocide” victim narrative that minorities and the outside world want to destroy them. Instead, he encourages people to show the compassion that people showed him all those years ago even when he didn’t deserve it. “I don’t know if any racist on earth changed their minds from being punched in the face. If anything that made them more violent, more racist. I can tell you that compassion does work.”

Alicia Landsberg is an ADL New England associate board member.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE