Rachel Genuth was a 15-year-old girl from Sighet, Hungary, when British forces liberated her from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on April 15, 1945. Seventy-five years later, her daughter, Bernice Lerner from Boston, has published Rachel’s story, as well as that of Rachel’s liberator, Brigadier Hugh Llewellyn Glyn Hughes, in one volume.

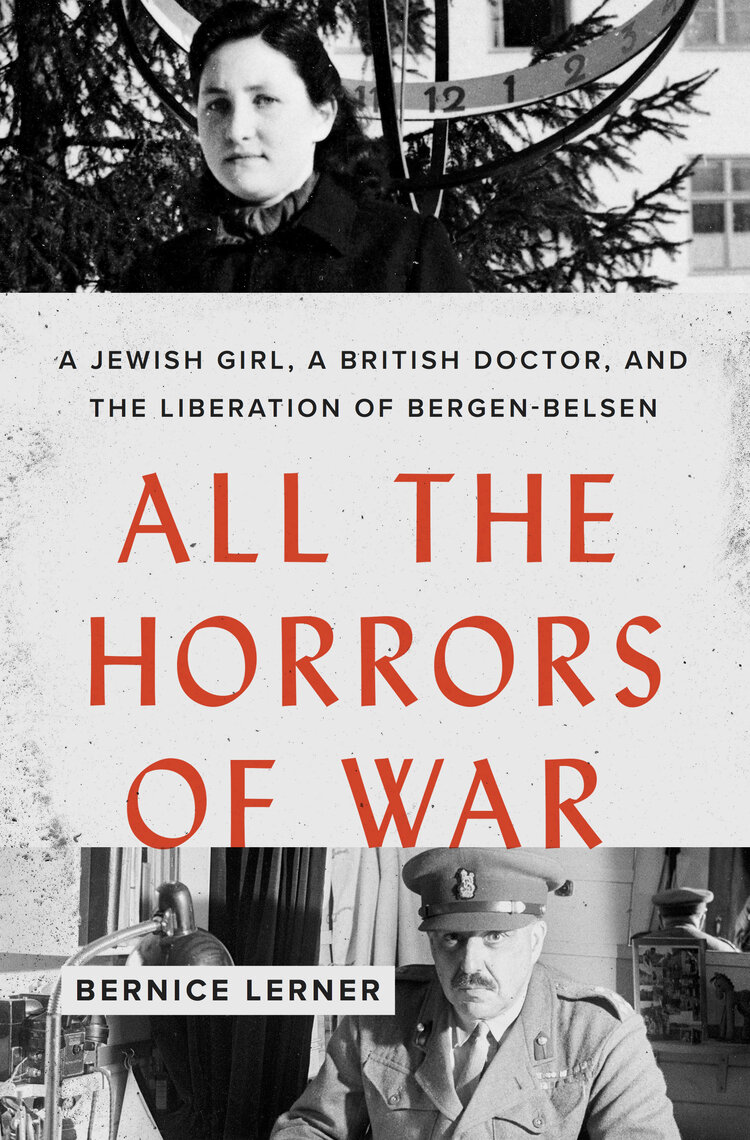

Although Rachel and Hughes never met, their stories naturally align in Lerner’s meticulously researched and compelling new book, “All the Horrors of War: A Jewish Girl, a British Doctor, and the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen.”

Lerner spent 15 years researching “All the Horror of Wars,” a project that involved mapping out the various battles that Hughes and the 8th Corps fought on their way to liberating Bergen-Belsen. Intertwined with the story of Bergen-Belsen’s British liberators is Rachel’s time at Auschwitz, the Christianstadt labor camp and a forced five-week march across the Sudetenland, during which she nearly died.

In choosing to focus her book on the last year of the war, Lerner presents the history of the Holocaust in thorough detail. She recently spoke to JewishBoston about researching the book, her mother’s miraculous survival and Hughes’ extraordinary lifelong empathy for the people he saved.

How did you unearth such intimate details about your mother’s journey?

There are still things I want to know. I never formally interviewed my mother. We were just in the habit of having these conversations since I was a little girl, where I asked her about her past. A lot of her stories didn’t have anything to do with the war. They were these exotic tales about very different cultures, like Romania and Sweden [where she lived for almost a decade after the war].

When I was a teenager—the age she was when all these horrible things happened to her—she told me her story. Over the decades, I would have a question for her, and she answered me. When I started to write the book, I wanted to know certain details. For example, when I asked her what she was wearing on the death march [through the Sudetenland], I framed the question as, “I hate to ask you this, but do you remember what you were wearing at this particular point?” Sometimes I’d send her questions in an email. That was good because she didn’t have to answer on the spot.

Your book is so well-researched. How long did it take you to write these narratives?

It took me 15 years. I didn’t originally set out to write about my mother. I originally had the idea of writing a biography of Brigadier Glyn Hughes. He was an Oskar Schindler-like character, and I thought people should know about him. I went to London and met his daughter before she died. I spoke with his son before he died. It was a race against time, but I tried to meet the key people who knew him. At some point, I decided to write a dual biography. I did more writing and research and, in the end, crafted my mother and Hughes’ stories over the last year of the war.

Did your mother ever meet Glyn Hughes?

No, she didn’t know who liberated her. She fell unconscious a few days after the British came in and was very sick. But I wanted to know how she got from a horrible, dung-infested hut to a makeshift hospital. How did she get from point A to point B, and then what subsequently happened? Then I wanted to know, what were her struggles and the struggles of the other survivors? And what were the liberators faced with?

What does your mother think of the book?

I think she’s very pleased. We’re all really thrilled that we’re alive to see the publication of it. When she reads the book, she’s still moved to tears. It resonates with her. But it’s very hard to write someone else’s story. I don’t know even now if everything is exact. We’ve talked about where there might be a little bit of discrepancy, and she’s read many drafts over time. Overall, she’s delighted to see it come to fruition.

She also learned so much from the book. She didn’t know there was a Glyn Hughes. She didn’t know the political decisions behind the rounding up and deportation of the Jews from her town of Sighet. As I was writing and she was reading, she was getting a broader context.

What do you hope your book will contribute to the literature of the Holocaust?

I wanted to lift these stories into bold relief. For personal reasons, I wanted to name key people. At least a few of the 6 million might be recalled and remembered. I also wanted to lift Brigadier Hugh Llewellyn Glyn Hughes into bold relief. I thought he deserved to be as well-known as Oskar Schindler for his post-war relationships with survivors, for his efforts, for his caring, for his empathy, for sacrificing his career trajectory like Chiune Sugihara from Japan. We don’t know why Glyn Hughes wasn’t promoted after the war.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?

I want people to take away an example of someone who displayed empathy. Glyn Hughes saw people at Bergen-Belsen who no longer looked like human beings. He saw these skeletal beings. But he also saw, as a doctor and a human being, the sacred in all people. We need these heroes to emulate and look up to, and to keep their stories in the back of our minds if we encounter the other. When we encounter the stranger, how do we receive them? How do we look at them? What kindness do we display? Glyn Hughes did this in so many areas of his life.

I also want to point out that people often don’t understand a lot about the Holocaust, even very knowledgeable people. They may not have known the difference between Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen and how things evolved during the war. They may not know what happened to the people who survived the gas chambers and the shootings. People were liberated in all kinds of ways and in all sorts of places. But Bergen-Belsen was the largest of the camps, where there were so many people who had survived so much.

This interview has been edited and condensed.