This year, Chanukah arrives right after Thanksgiving! The last time we saw this near-overlap was in 2013 (and before that 1888 and 1899). Since then, Google Docs has learned how to autocorrect my spelling of “Thanksgivukkah,” and I feel like the Jewish people have really arrived. The truth is that Chanukah always arrives at the same time—the 25th of Kislev; when our lunisolar Hebrew calendar meets the Gregorian calendar, it feels like it’s “early,” and no matter how we debate the spelling of (C)(H)an(n)uk(k)a(h), in Hebrew it’s always spelled חנוכה.

When you think about the Festival of Chanukah, no matter how you spell it, does your mind immediately turn to the brave Maccabees, tasty chocolate gelt, dreidels and latkes and the miracle of eight days of oil? You’re not alone! The Chanukah story in the Book of Maccabees is such a fabulous story, rooted in the rabbinic period (i.e. it’s not actually in the Torah) and reminds us of incredibly powerful themes of religious freedom, resisting assimilation and what happens when a small and mighty group of people stand up with courage and conviction against their oppressors. These elements and themes, as well as the seemingly historic debate between sour cream or applesauce latke toppings, are more than enough to catalyze for eight days of Chanukah celebration! But let’s consider a lesser-known story in Jewish tradition and how it might impact our celebration this year.

Related

Here’s one heroine to get us started: Judith’s story is written in the Book of Judith, a book in the apocrypha, which is a group of Jewish texts written in Greek during the Hellenist period, including stories, prophetic writings, sermons and more. The apocrypha texts are not part of the Jewish literary canon, which means that unless you have a Ph.D. in Second Temple literature, you may not know about these texts. (I didn’t until rabbinical school when I studied them with my beloved professor, Rabbi Aaron Panken, of blessed memory.)

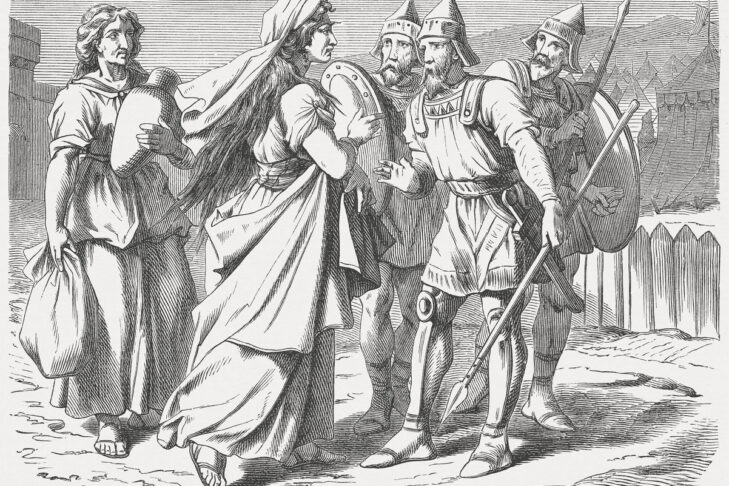

To paraphrase an excellent summary from Ritualwell, Judith was a pious widow living in a city besieged by a king whose 40,000 warriors caused the Jews great suffering. So, Judith devised a plan. She removed her mourning clothing and instead dressed in beautiful clothing and jewels and went out to the city gates. “Open the gates,” she said, “for perhaps God will perform a wonder for us.” But the guards wouldn’t open the gates because they feared she would plot against them. “Heaven forbid,” she promised, and took an oath before them. Amazingly, the guards opened the gates.

Judith, the text says, was a stunning woman, and when the king, Holofernes, saw her, he wanted to marry her. Judith agreed. On the night of their engagement feast, the story goes that Judith fed King Holofernes lots of salty cheese to increase his thirst, which he quenched with wine. By the end of the night, he had so much to drink that he fell asleep. When everyone left for the night (spoiler alert!), Judith lifted her sword and cut off the king’s head. She took the king’s head to the gates of Jerusalem to tell everyone what she had done.

It’s a powerful and gruesome tale, and unlikely to become a PJ Library book for kids. But what does this powerful story mean to us?

Professor Judith Kates, a retired professor of Jewish women’s studies at Hebrew College, offers this insight: “Judith is a story of expectations transformed. The use of a female character as both symbol and literal embodiment of the community of Israel has a long history in Jewish texts by the time of the Book of Judith. But the transformation of that female body from victim to rescuer suggests a more radical message. The female body, for centuries the symbol of the community as victim of oppression, becomes the means of rescue…. Standing ‘outside’ holding the enemy’s head in her distinctively female hand, she symbolizes a human community which can mold its vulnerability and apparent powerlessness, its ‘femininity,’ into resources of strength. Her presence, startling us into awareness of God as the God of surprises, brightens the Hanukkah lamp we place in our homes at the meeting point of inside and outside.”

Mizrachi and North African communities observe the heroism of Judith (and other women like her) with Chag HaBanot, the Festival of the Daughters. This occasion is celebrated on the sixth or seventh night of Chanukah, aligning with the Rosh Hodesh new moon of the Hebrew month of Tevet. It is celebrated with various customs, including eating cheese, sweet foods, gift giving and rejoicing in the power of women in ancient and modern times. I’m not Mizrachi or North African, so I recommend checking out these resources by a writer who holds this identity.

Most important, I feel like the heroics of Judith and the commentary offered by our modern Judith, Professor Kates, give us a powerful charge to carry with us into this Chanukah. Consider the powerful injunction of pirsum hanes, the encouragement to publicly proclaim the miracle of Chanukah by bringing our Chanukah menorahs to shine in our windows. The word pirsum in modern Hebrew means “to advertise,” and while it might seem intimidating or scary, consider embodying the strength and power of Judith and the Maccabees to advertise proudly to the world who you are and what Judaism stands for, which is that even in the darkest of days, each of us has the power to illuminate the world with the light of freedom and hope.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE