The 33rd Annual Boston Jewish Film Festival, which runs Sunday, Nov. 7, to Sunday, Nov. 21, will virtually screen 38 films, documentaries and shorts. The impressive lineup includes themes that range from Holocaust stories to American biographies to a moving dramatization of the plight of Kurdish refugees.

Although purchasing a film festival pass means you can access the lineup at any time, organizers have designated opening and closing films. “Robert Brustein: A Celebration” will introduce the festival, with a pre-screening tribute to Brustein, often called the “Father of American Modern Theater,” and his wife, Doreen Beinart. “Persian Lessons,” an offbeat, weirdly tense story based on true events in the Holocaust, closes the festival with a screening and live appearance by the film’s director, Vadim Perelman.

Check out the highlights below and find a full events listing here.

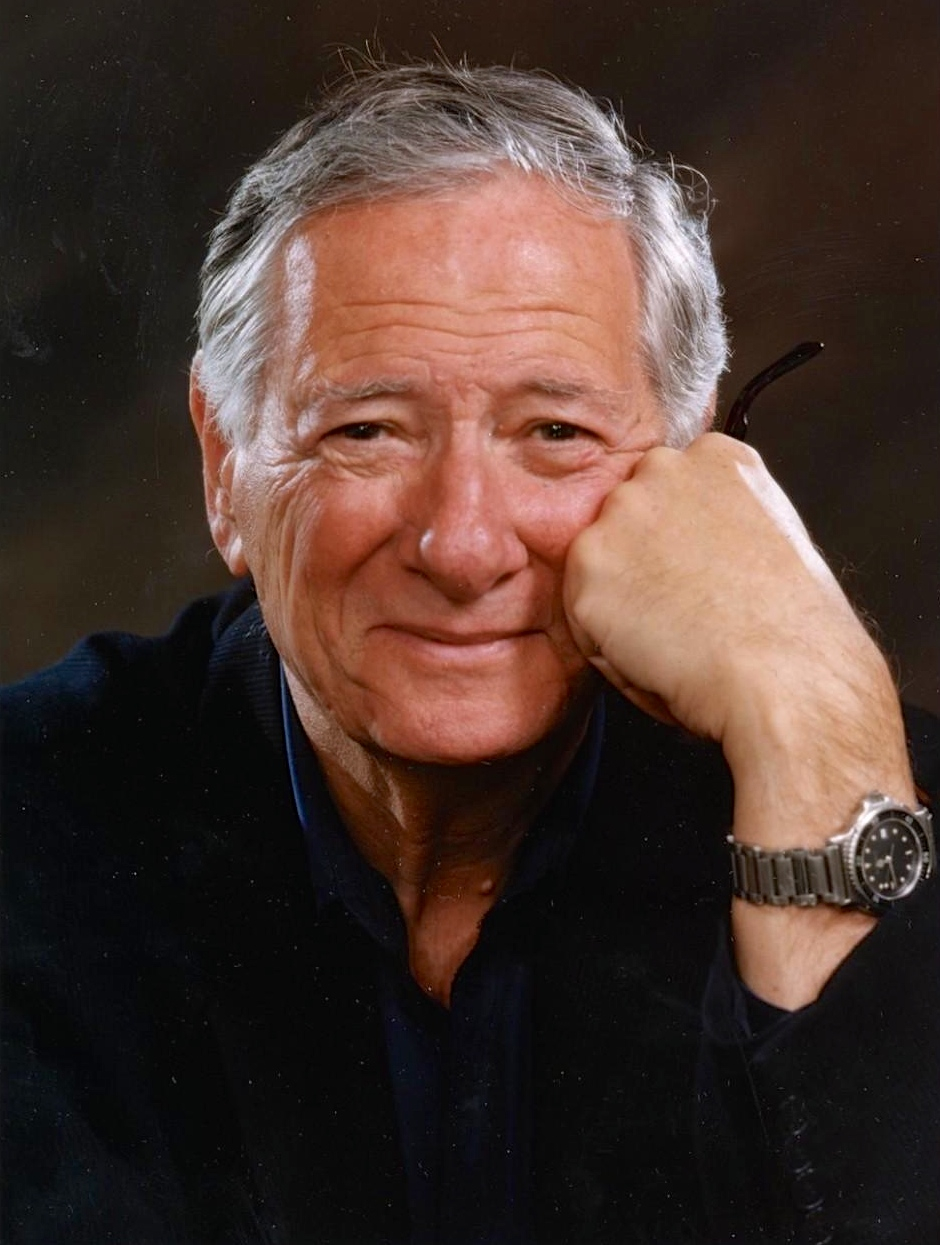

“Robert Brustein: A Celebration”

“Robert Brustein: A Celebration,” an hour-long tribute to Brustein’s impressive and enduring career, amply demonstrates why he is acknowledged as the “Father of American Modern Theater.” Designated as the Boston Jewish Film Festival’s opening night film, “A Celebration” features former students and mentees praising Brustein’s gifts as a teacher, director and actor.

A fun fact that viewers learn early on about the eloquent Brustein, now 94, is that he took elocution lessons as a child to master pronouncing his Ls. At Amherst College, he pursued his love of theater and earned a Ph.D. in dramatic literature at Columbia University. Along the way, he attended the Yale School of Drama, where he later returned as its dean in 1966.

During his 13-year tenure at Yale, Brustein founded the noted Yale Repertory Theatre, where the careers of acting powerhouses such as Meryl Streep, Tony Shalhoub and others were launched. At Yale, Brustein was very much a working dean, writing, directing and acting until the university’s then-president, A. Bartlett Giamatti, fired him. The next year, Brustein decamped to Harvard University to found the American Repertory Theater (ART).

At the ART, Brustein directed Shalhoub, Shalhoub’s wife, the actor Brooke Adams, and Broadway luminary Cherry Jones. They all appear on camera, offering heartfelt tributes to Brustein as a mentor and director. Jones recalled that Brustein allowed his actors to “fail and succeed.” Brustein’s second wife, Doreen Beinart, a trustee of the ART, lovingly praises her husband. The director Julie Taymor recalls being hired as a costume designer at the ART and then mentored as a director by Brustein. In 1986, Brustein won a Tony Award for directing the Broadway-bound production of “Big River” at the ART.

“A Celebration” bears out Brustein’s observation that no other medium “provokes, incites and excites” like the theater. And no one has done more for American theater than Robert Brustein.

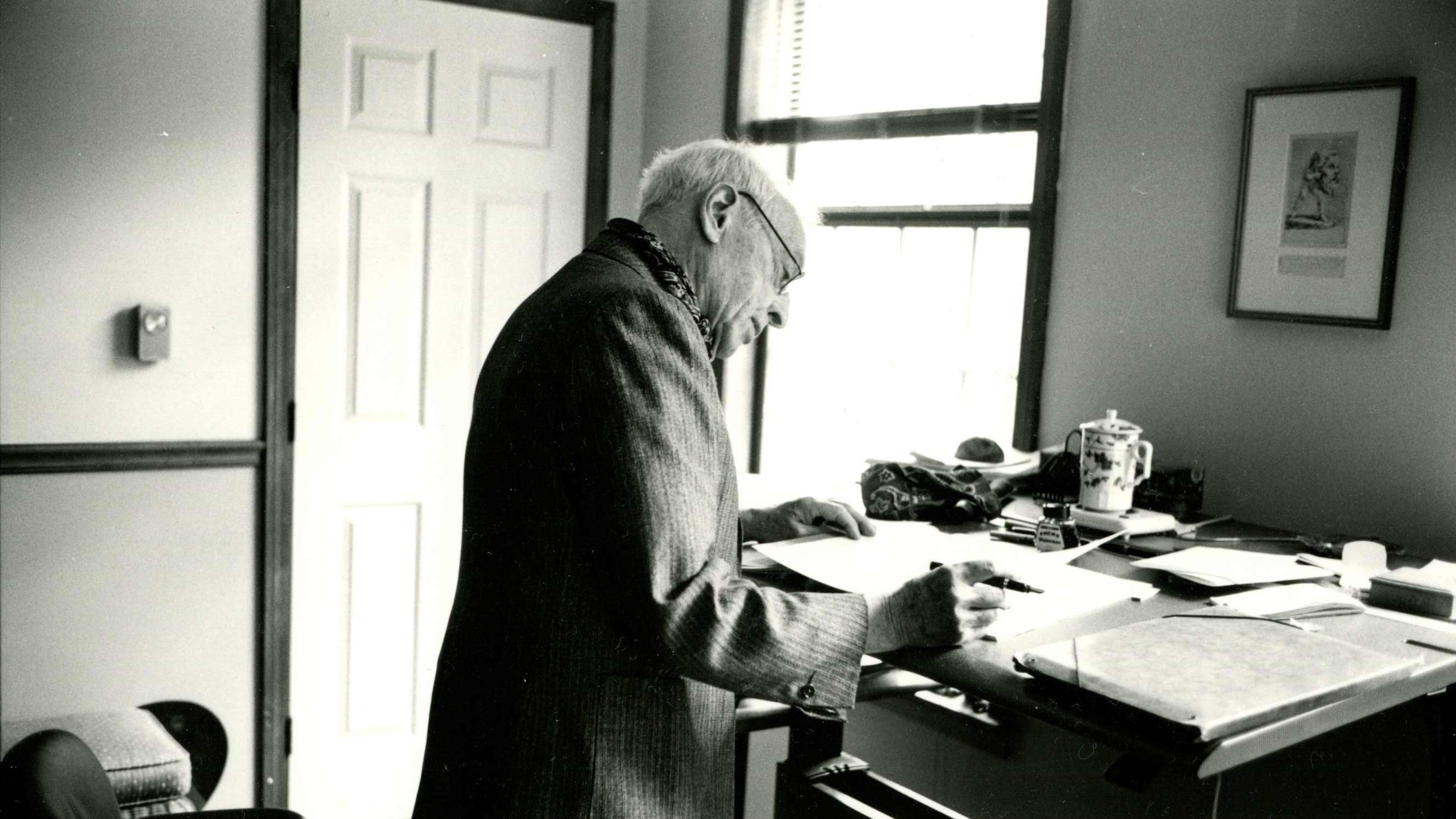

“The Adventures of Saul Bellow”

The literary critic James Wood described Saul Bellow as the “greatest of American prose stylists in the 20th century.” Proving the point, Bellow has been honored with three National Book Awards, a Pulitzer Prize and the greatest literary accolade of all, the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1976. Bellow has been described as a “physical writer,” taking in the specificity of his surroundings. His work is a stark contrast to the minimalism and lean sentences of another American Nobel laureate, Ernest Hemingway.

The release of “The Adventures of Saul Bellow” coincides with the centennial of Bellow’s birth and the 10th anniversary of his death. Israeli American director Asaf Galay will be on hand to discuss the film on Sunday, Nov. 14. Bellow was born in Quebec and was 4 years old when his family moved to Chicago, the city associated with him and his work. A parade of literary luminaries like Philip Roth, Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis highlight Chicago’s prominence in Bellow’s work as they offer analyses of his books.

Bellow was married five times and had three sons and a daughter. We hear from his sons—Adam, Daniel and Gregory—as well as two of his wives, Alexandria and the much younger Janis Freedman-Bellow, who survived him. His sons comment on their father’s serial marriages and his propensity for beautiful women as they remain protective of their mothers. Galay does not shy away from conveying that Bellow was also regarded as narcissistic, racist and misogynistic at various points in his life. On camera, the writer and critic Vivian Gornick makes a compelling case for all three descriptors.

It makes for an intriguing parlor game to think how critics and readers today would regard Bellow’s 14 novels, his four nonfiction volumes of essays, letters and memoirs, the three short story collections and play. However, there is little doubt he will always be known for the controversy he stirred as a Trotskyite-turned-right-wing polemicist. And as Gornick bluntly asserts, he represented “the misogyny of the male American novelist.”

“Leaving Paradise”

An Israeli-produced film honored as the best documentary at the Haifa International Film Festival, “Leaving Paradise” unspools the journey of a large Brazilian family as they establish a commune in Brazil’s interior. The family’s patriarch, Cleo, clings to a utopian vision of his wife and 15 children living and farming together. But such dreaming does not sit well with many of the young adult children. The family is divided when the older sons discover the family’s Jewish roots, which brings them to practice a folksy Judaism, replete with dreams of moving to Israel. At one point, they summon a rabbi from Buenos Aires to guide them toward conversion.

However, life becomes complicated as Cleo resists making aliyah and one of his sons goes to Israel on his own. Another son’s wanderlust is stymied as he dreams of traveling throughout South America. In the end, it’s unclear how many family members will ultimately convert and if the elder son’s conversion, performed in Argentina, will be accepted in Israel. There is no resolution for what the family wants collectively or individually. There is only the stunning Brazilian forest in which to contemplate the very Jewish theme of L’ech L’cha—the chapter in Genesis in which Abraham and Sarah leave the familiarity of their home and venture forth to create a new nation.

“The Seven Boxes”

In 2002, Dory Sontheimer of Barcelona found seven boxes of letters and documents—a very Jewish and mystical number—cleaning out her deceased parents’ basement. It turns out the materials were a treasure trove that allowed Sontheimer to piece together a family history of which she was unaware. Sontheimer, whose parents had escaped Nazi Germany in the early 1930s, was brought up Catholic to avoid persecution in Francisco Franco’s fascist Spain. However, before she married, her parents felt that they had to inform her that she was Jewish. As Sontheimer went through the boxes’ contents, she discovered her maternal grandparents had perished in Auschwitz and the Nazis had murdered 36 other family members.

Sontheimer’s newfound knowledge launched her on a journey where she met more than 20 members of her family from all over the world for the first time. Among them was Brookline resident Michael Gruenbaum, who was from a distinguished Jewish family in Prague. Gruenbaum and his mother and sister—the father did not survive—were imprisoned at the Theresienstadt concentration camp, a way-station from which Czech Jews were deported to death camps in Poland. It also served as a model camp to fool Red Cross observers into believing the Nazis treated inmates humanely.

In the end, Sontheimer finds relatives in Tel Aviv, Buenos Aires, Prague, Boston, Montreal, New York and London. They reunite in Barcelona, where an emotional Sontheimer exclaims that the grandparents she never knew could not have imagined such a joyous gathering.

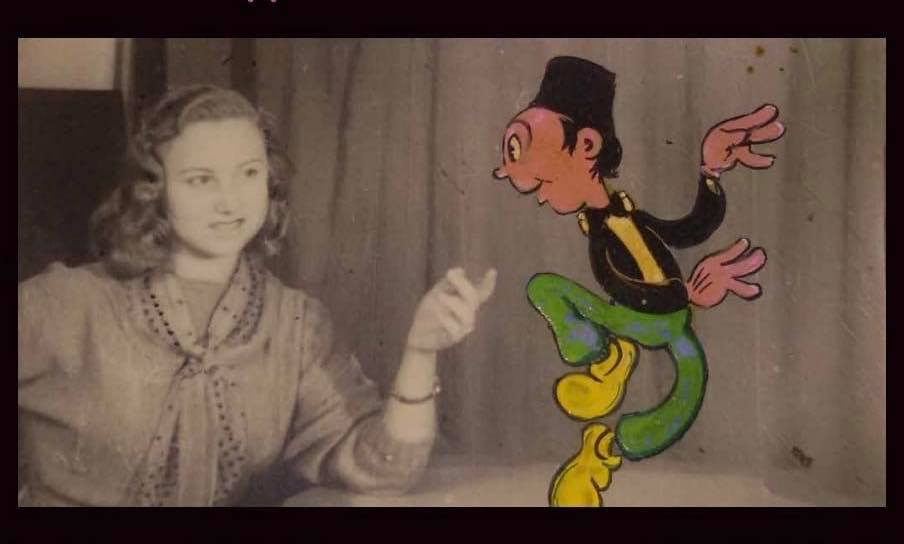

“Bukra Fil Mish Mish”

The title of this delightful film, which showcases the animated films of the three Frenkel brothers of Egypt, is an Arab saying that means “when the apricots bloom.” Apricot season is brief in the Levant and the implication is that something is as unlikely to happen as harvesting apricots. To that end, family legend adds that when Salamon, David and Herschel Frenkel were looking to fund their animated film “Mafish Fayda,” a banker told them money would be forthcoming bukra fil mish mish.

The Ashkenazi Frenkel brothers moved to Egypt in the 1920s after they were run out of Jaffa as suspected Russian spies. In Cairo, they became the first animators in any Arab country, and their films attracted a significant following. Part of the brothers’ success was due to their distinctive division of labor; David was the dreamer, Herschel was the marketing maven and Salamon handled the technical aspects of making the cartoons.

The brothers’ filmmaking career was derailed after the founding of Israel in 1948 when life became impossible for Jews in Arab countries. The dangers Jews faced in their homelands are reflected in cartoons that the brothers made of marauding youths attacking their best-known character, Mish Mish Effendi.

The Frenkels eventually immigrated to France, where they dabbled in animation and filmmaking. But in France, they never gained a foothold in the industry. They left reels of film that languished for 60 years in a basement. Only Salamon married, and he pointedly asked his sons to destroy the films. The eldest, Didier, refused, and had them restored. Not only was their life’s work saved, but the Frenkel brothers were finally recognized and dubbed the “Egyptian Walt Disney.”

“Neighbors”

This affecting coming-of-age story follows 6-year-old Sero, who lives in a Kurdish village in northeastern Syria, where the Turkish border is tantalizingly close. It is the early 1980s, and the Kurdish locals welcome a new teacher to town—a Ba’ath Party loyalist and fervent supporter of the brutal dictator Hafez al-Assad. Intimations of Nazism come out as the teacher refers to al-Assad as the fuhrer and gives graphic lessons inciting violence against Jews.

Sero cannot reconcile what he is taught in school with his affection for his Jewish neighbors—beloved friends for whom he lights fires on Shabbat. This poignant film showcases the strength of community, the moral courage of the Kurdish people (Sero’s uncle is a Kurdish freedom fighter who flees to the mountains) and the triumph of love over hate. Sero’s father risks his life to help his Jewish neighbors, stripped of their Syrian citizenship, escape to safety. At one point, a Kurdish villager asks the fanatical teacher, “What would your life be like if Israel were not your enemy?” The question resonates in this heartrending film.

“Persian Lessons”

Serving as the festival’s closing picture, it’s difficult to place “Persian Lessons” among the cinematic tales of the Holocaust. Gilles, a Belgian Jew and the son of a rabbi, narrowly escapes a firing squad in the woods. Only moments before, he traded his sandwich with another prisoner for a book of Persian fairytales. He uses the book as a prop to convince the Nazi guards, who have just murdered his entire transport, that he is not Jewish but Persian.

As it happens, Koch, the commandant of the local concentration camp in occupied France, is looking for a Farsi tutor. An accomplished chef in civilian life, Koch dreams of opening a restaurant in Tehran, where his brother has fled the war. The terrified Gilles agrees to teach him Farsi, a language he has never heard spoken. Gilles invents vocabulary and grammatical rules as he goes along. He relies on mnemonics to remember the gibberish he concocts from one day to the next.

As the story unfurls, Gilles transcends his prisoner status and becomes Koch’s beloved teacher and confidante. It’s a complicated and fascinating dynamic for which Koch goes to great lengths to protect his tutor from deportation to a death camp. Yet at any moment, Gilles’s ruse can be discovered and Koch will not hesitate to have his teacher face a firing squad.

While not approaching the silliness of the old “Hogan’s Heroes” sitcom in which the Nazis were hopelessly foolish or the farcical plot elements of “Jojo Rabbit” and “Life Is Beautiful,” “Persian Lessons” relies on stereotypes of bad yet clueless Germans and the clever victims who live to tell their stories. It asks viewers to suspend belief, which can be both escapist and irritating in equal measure.

“Space Torah”

In some ways, the 25-minute “Space Torah” belongs to the Boston Jewish community. Dr. Jeff Hoffman, who is Jewish and was the first astronaut to bring a Torah to space, is on the faculty of MIT. Over the years, Hoffman has generously talked to audiences in Boston and throughout the country about his experiences in space, which included fixing the Hubble Telescope. Hoffman regarded the Hubble mission, his first in space, as an act of tikkun olam—a gesture to help “repair the world” so the Hubble could focus properly and capture incredible astronomical images.

This short film also captures the emotional moment on another mission when Hoffman unfurls the small kosher Torah he has brought with him to space and reads the opening lines of Bereishit—“In the beginning, God created heaven and earth.” It’s moving when Hoffman also recites the Jewish blessing in Hebrew for witnessing wonders of nature. A venture of Verissima Productions, “Space Torah” also recognizes Boston-area congregations Temple Emunah of Lexington, Temple Emanuel of Newton and Temple Sinai of Brookline in the film’s credits.

Short Film: “The Binding of Itzik”

The title of this quirky and provocative short film, winner of best narrative short film at the Berlin Underground Film Festival, works on many levels. The most obvious is the biblical reference to the near-sacrifice of Isaac by his father, Abraham. But it also takes a wholly different interpretation as it focuses on the film’s contemporary protagonist, Itzik. An anomaly in his ultra-Orthodox community in Brooklyn, Itzik is an unmarried middle-aged bachelor who lives with his niece’s family. He’s also a bookbinder—another level of meaning in the title—who has struck up a furtive online relationship involving bondage, role-playing and dominance and submission.

MeatMaster500 is the screen name of someone who plays the menacing role of dominator to Itzik’s online persona of the submissive woman. The intensity that inevitably comes with the deception masterfully builds in this 17-minute film. The ending, while teasingly open-ended, feels appropriate and even hopeful.

Director Anika Benkov will appear on Wednesday, Nov. 10, as part of the FreshFlix Short Film Competition directorial lineup.

Short Film: “Devek”

An Israeli production, “Devek” glimpses the loving relationship between mother and son, Naomi and Eliya. Naomi’s health is deteriorating and her despondent son, Eliya, brings her to a card reader. He is hoping for confirmation that Naomi is not dying. But it is impossible to ignore the signs of death around Naomi. When she takes a break outside from the intense reading, the fortune-teller tells Eliya that Naomi’s end is near. Yet when Naomi returns, she’s told her health will improve. At the end of the film’s 14 minutes, mother and son are floating peacefully in the Dead Sea. The symbolism of water appears to mark a return to the womb, with all the hope that birth and rebirth entail.

Director Uriya Hertz will participate in the FreshFlix Short Film Competition live conversation on Wednesday, Nov. 10.